Bella Watson // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

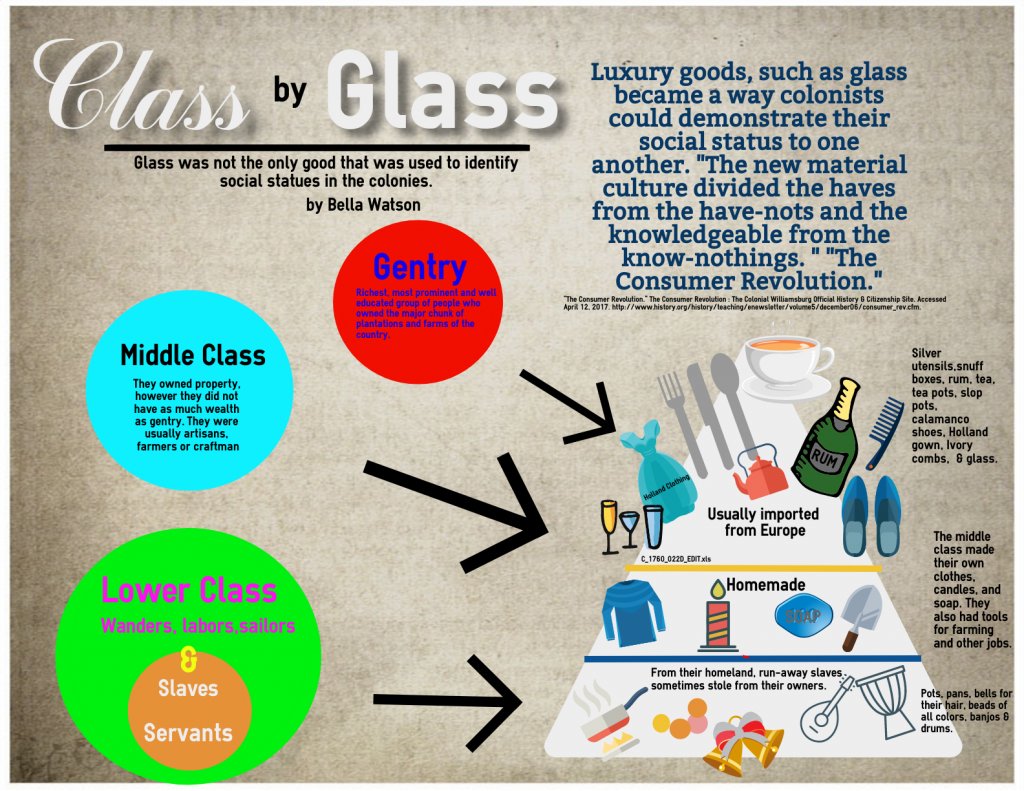

Glass has always been a mystery to me. Where does it come from? How is it made? Is it significant? From my research, I have discovered several customers purchased glass items in the 1760-1761 ledger from the Glassford and Henderson store in Colchester, Virginia. This discovery motivated me to dig deeper into the mystery of glass and reveal the unanswered questions.

History behind the Glass: With the opportunity to prosper in the New World, colonists needed to produce profitable goods. After all, the New World was abundant with raw materials needed for glassmaking: sand, wood, and ashes.[1] In England, glass was in high demand; however, the country lacked the appropriate resources to create glass. Although the colonists had the resources, they originally had no talented artisans to make the glass.[2]

Production in Jamestown: In 1608, the Virginia Company sent Dutch and Polish artisans to Jamestown, Virginia, as craftsmen to create various products, including glass. Within the year, the manufacturing of glass was established. After the “Tryal of Glasse” (samples of glassware that were produced) was sent over to England, the production in Jamestown was halted due to a population decrease.[3] Thanks to a nearby swamp, starving conditions and repeated epidemics created the need for a constant replenishment of new colonists.[4] In 1621, four Italian artisans were among a new shipment of colonists sent to Jamestown. These four men were to restart glass production. This venture was organized by Captain William Norton.[5] He created a well-organized plan that would ensure success in the glassmaking industry, however it did not start out as smoothly as he hoped. The production of glass was halted in 1622 because of bad weather, disease, and conflicts with Native Americans, though efforts would not completely cease until 1624.[6]

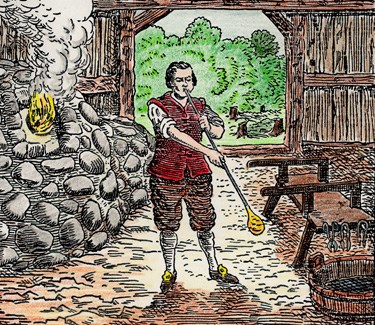

The Process: At Jamestown, glass was produced from silica in sand on the shores of the James River and alkali from limestone and potash.[7] After these materials were gathered, they were cleaned by either washing or extreme heating. The freshly cleaned materials were then liquefied in the furnace, which was fueled by wood from the surrounding area. These furnaces reached up to 2,080 Fahrenheit which enabled the silica and alkali to form into crystals. It was then melted into a molten material ready to be blown into a finished piece.[8]

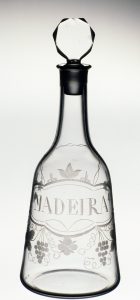

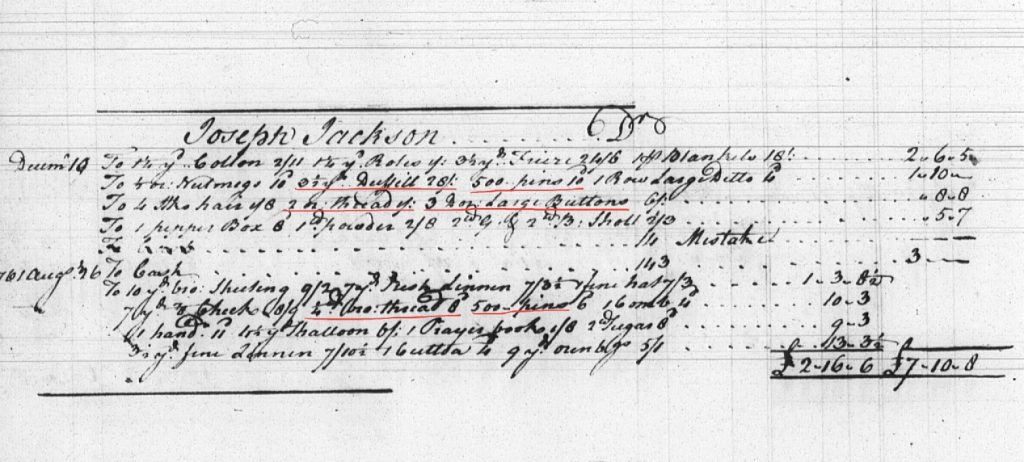

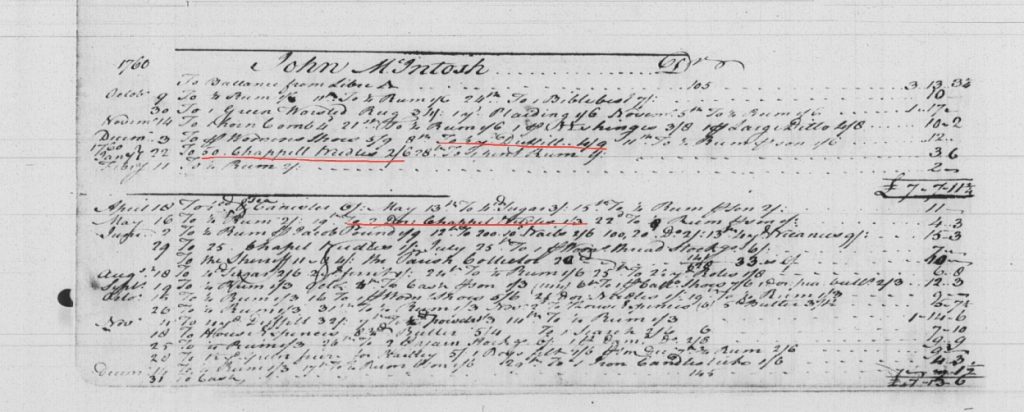

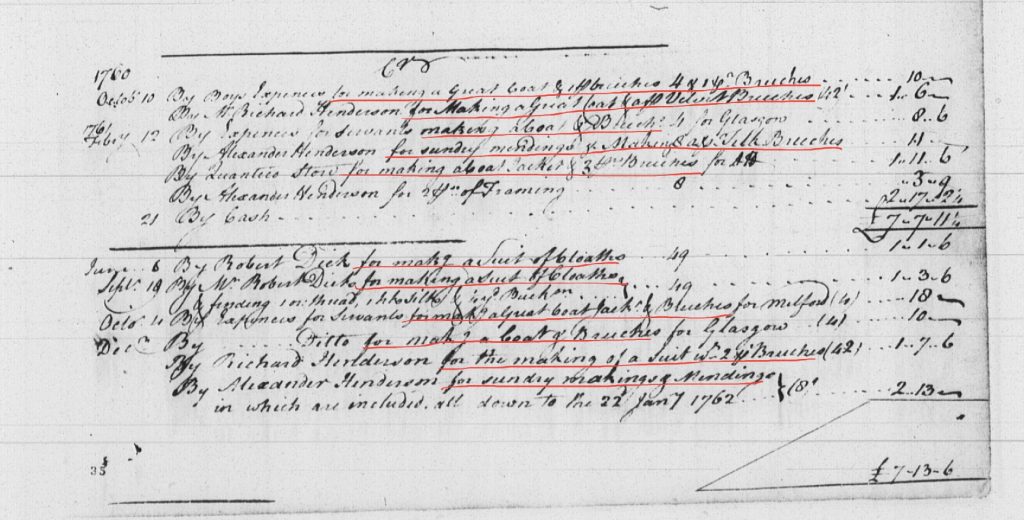

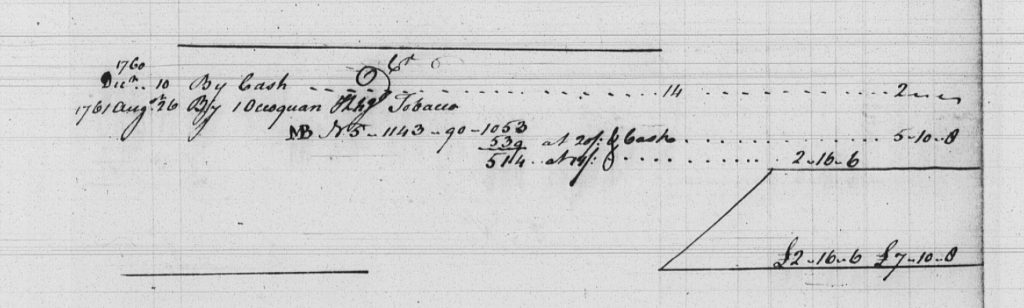

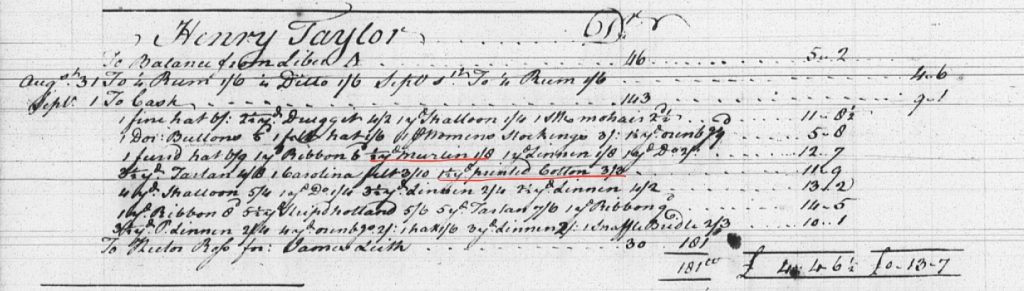

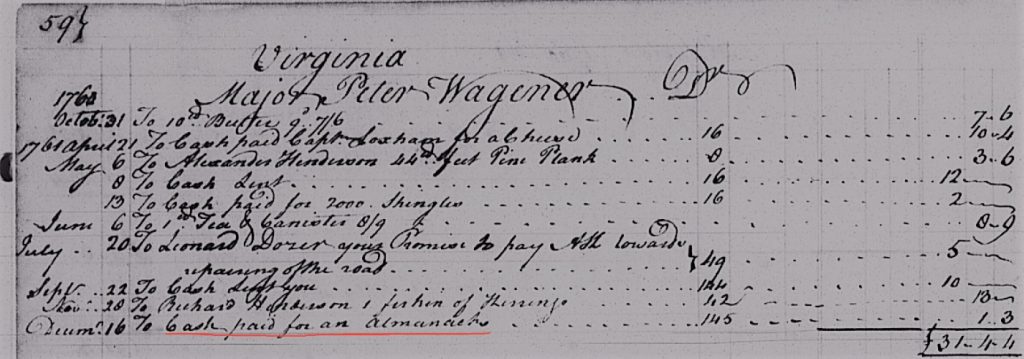

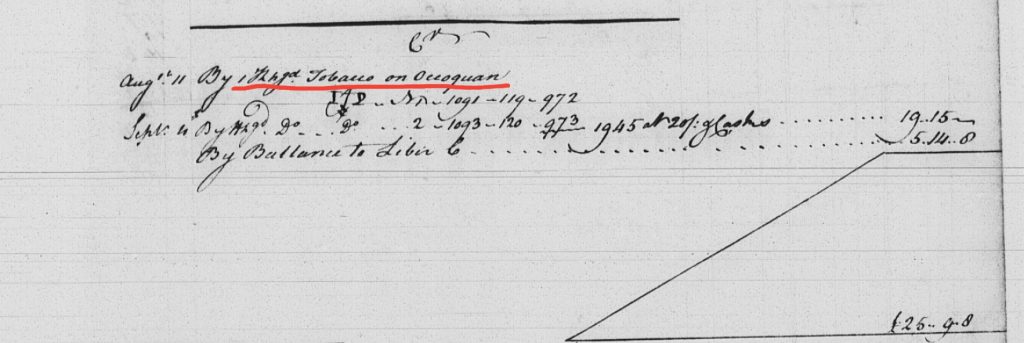

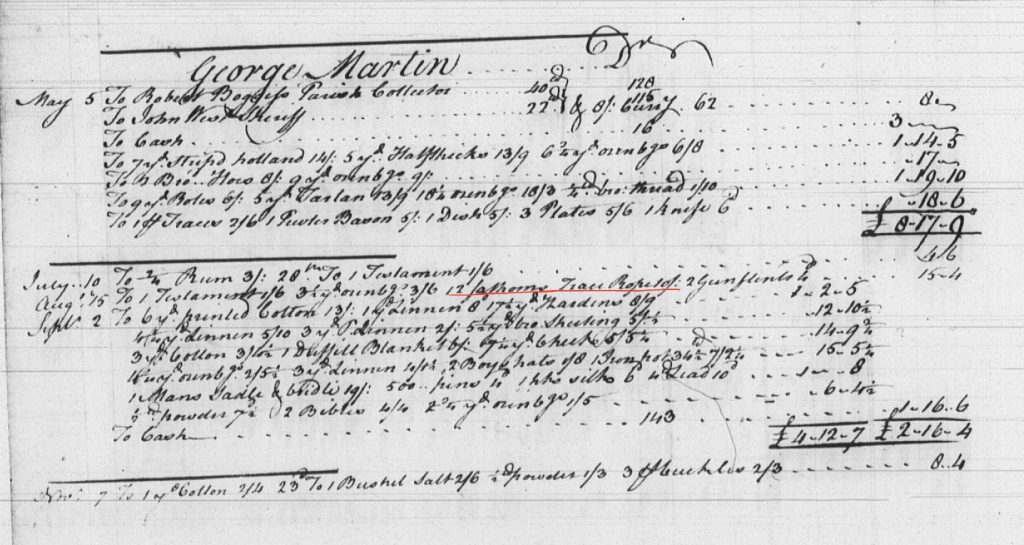

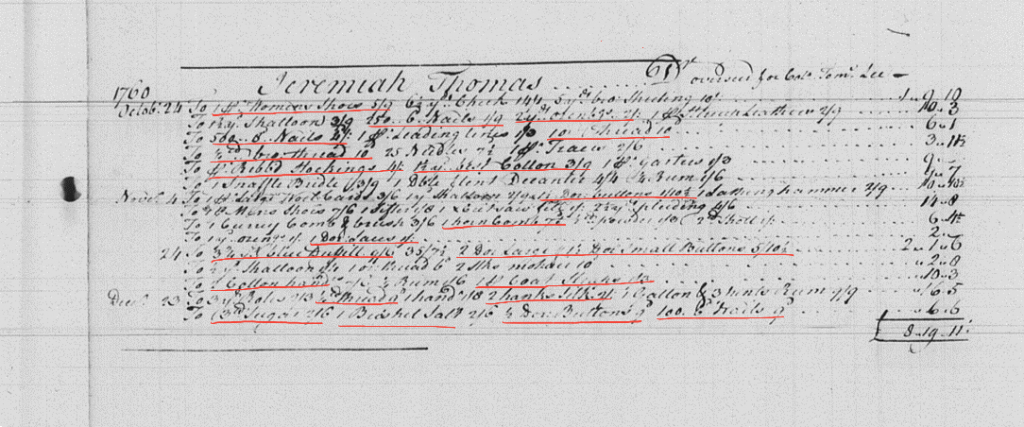

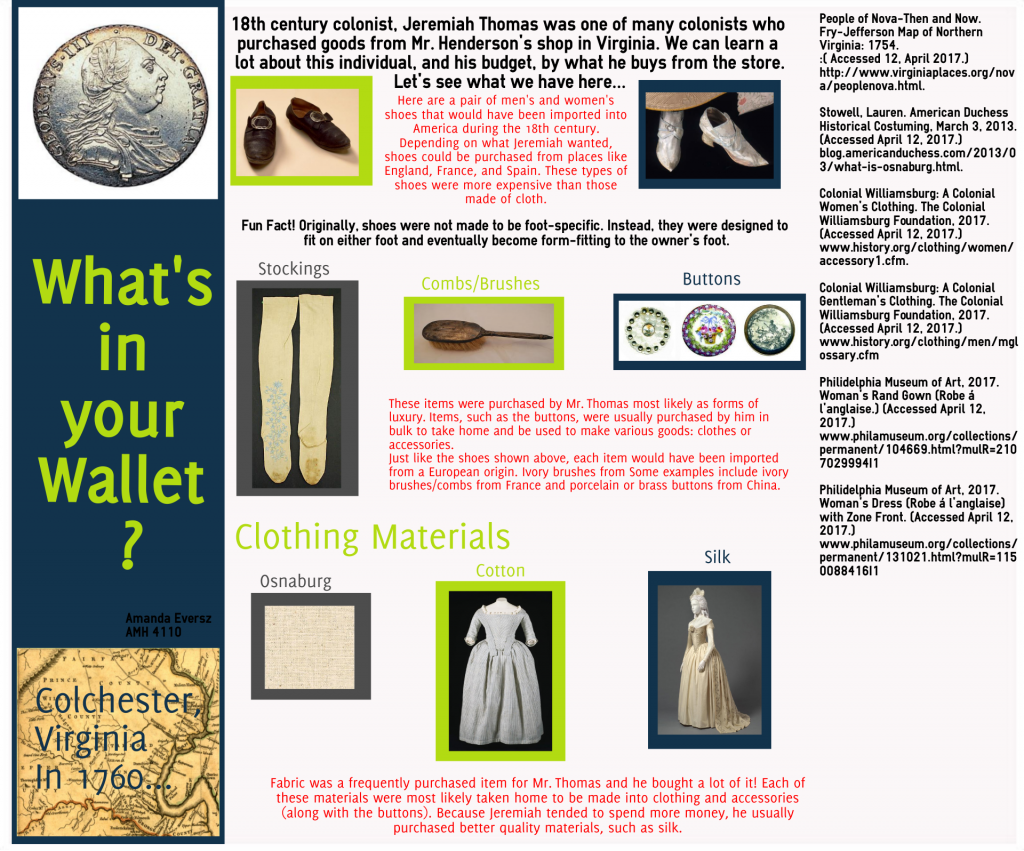

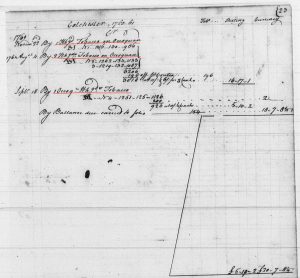

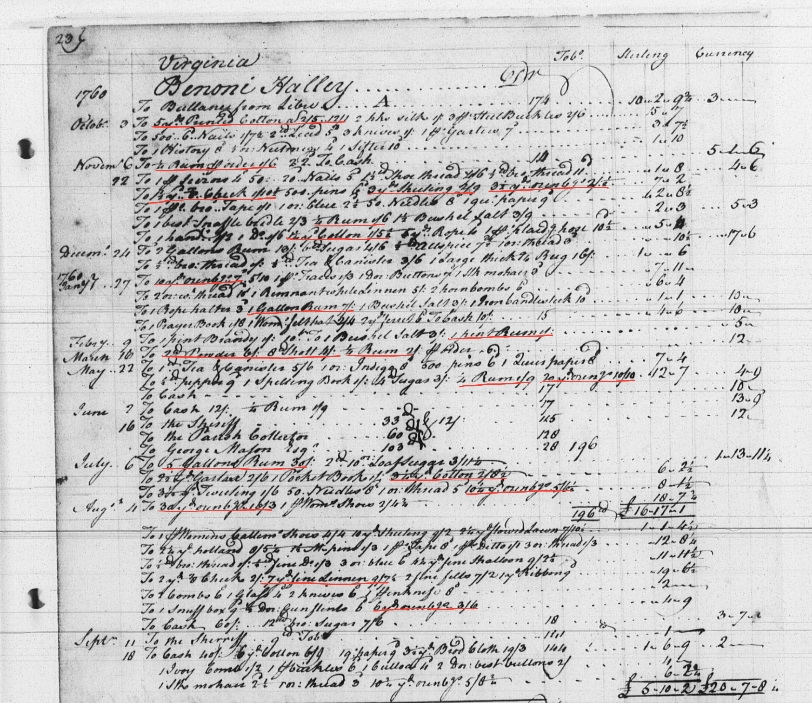

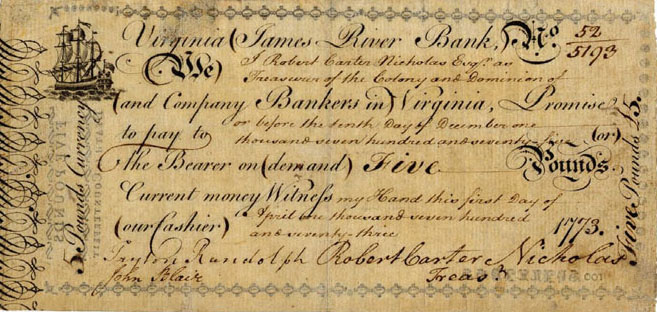

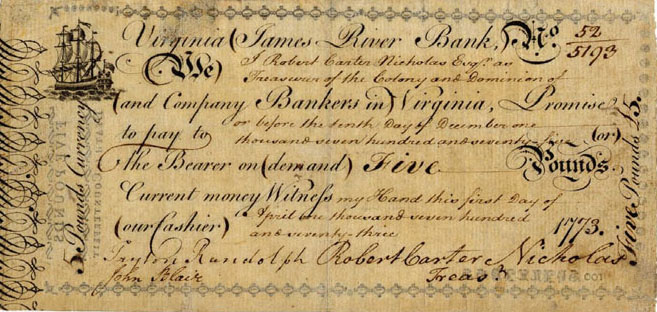

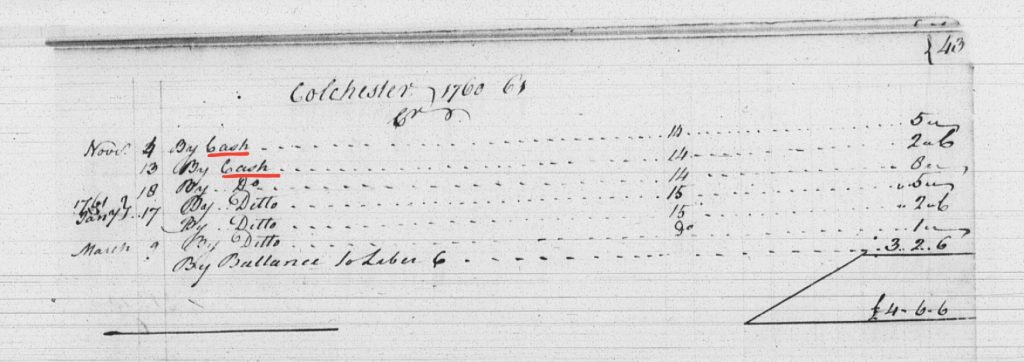

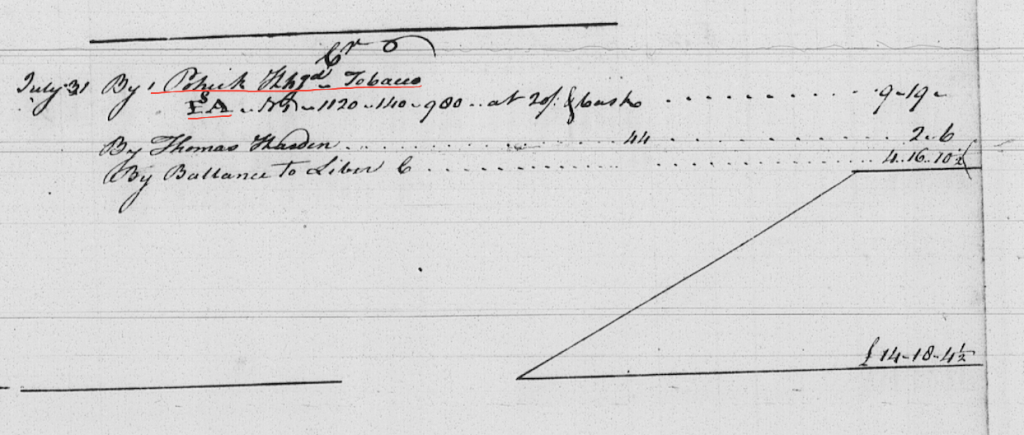

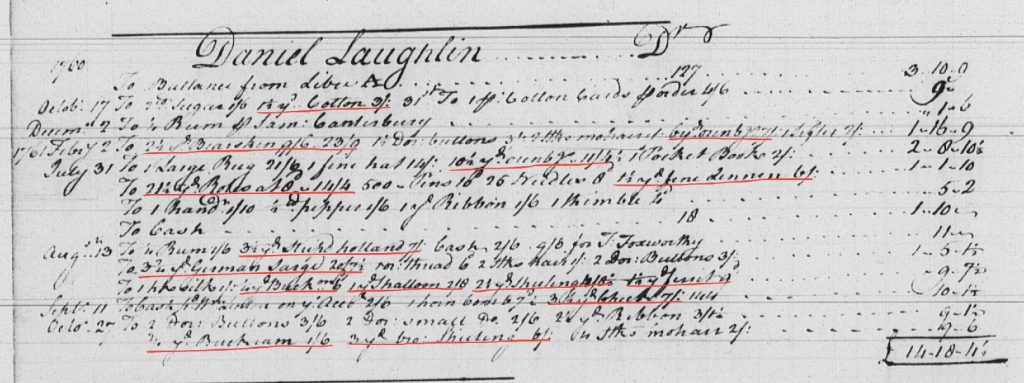

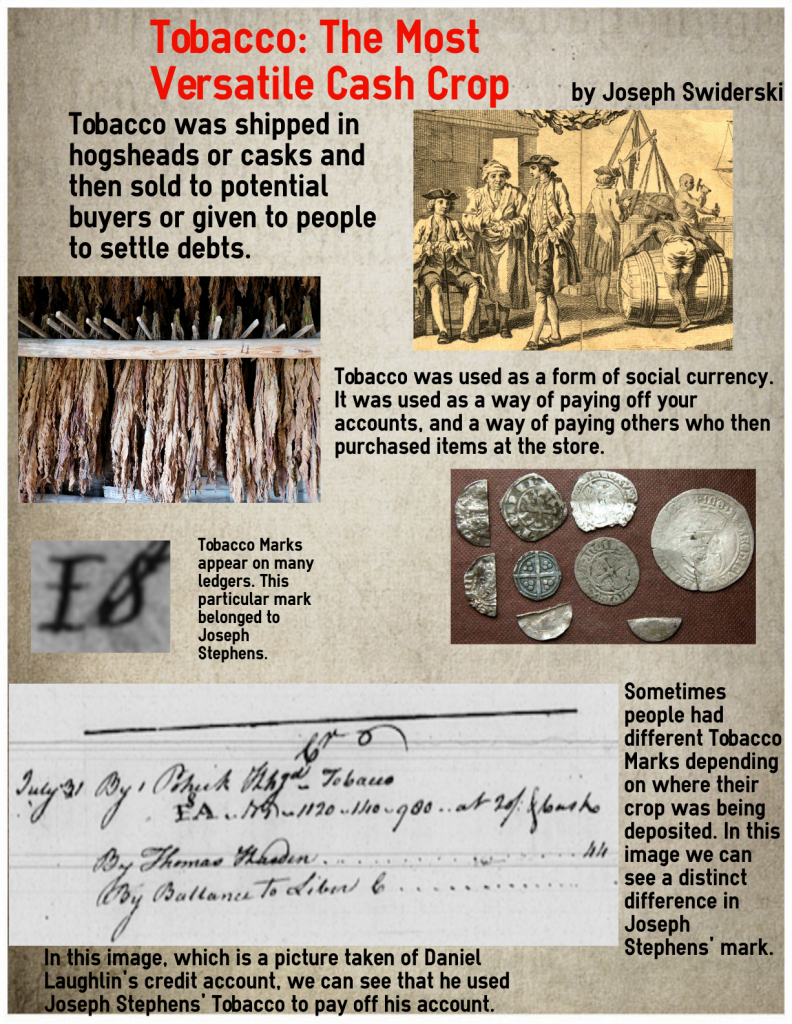

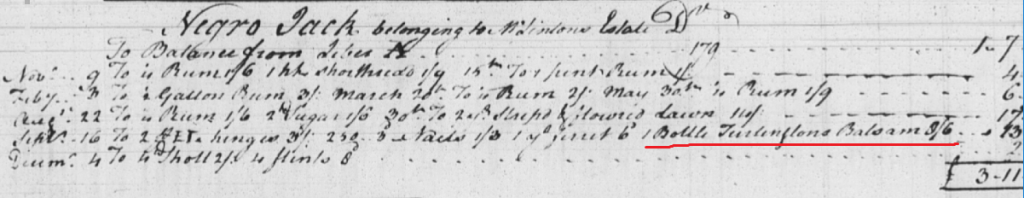

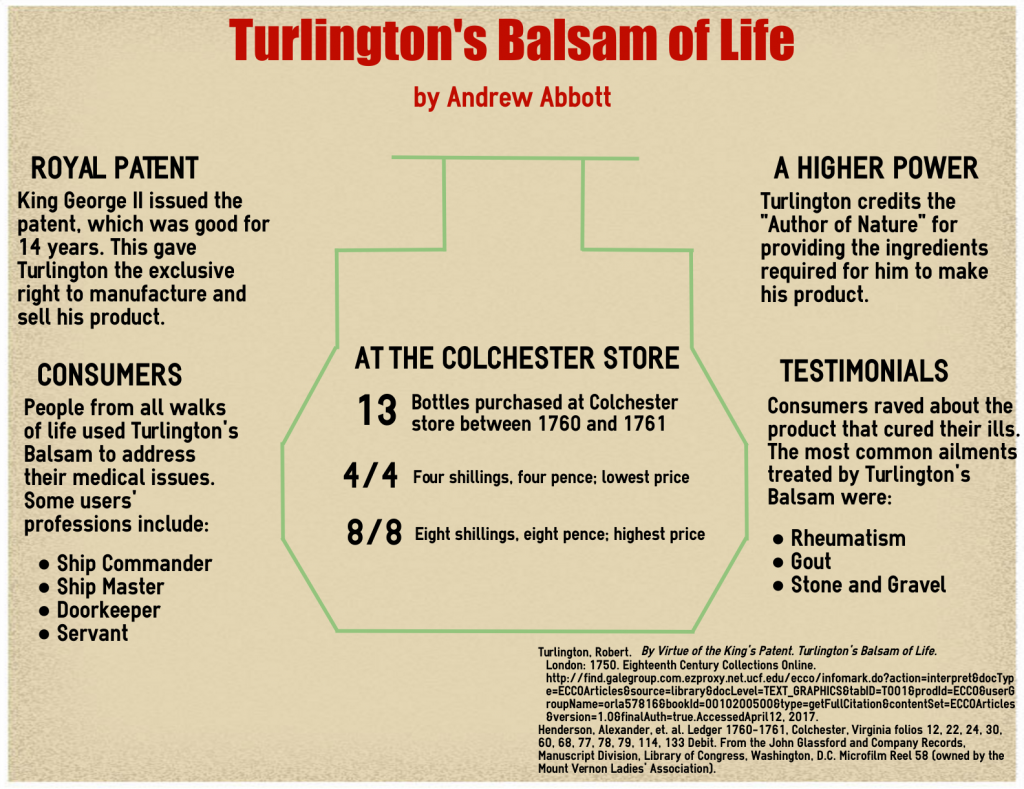

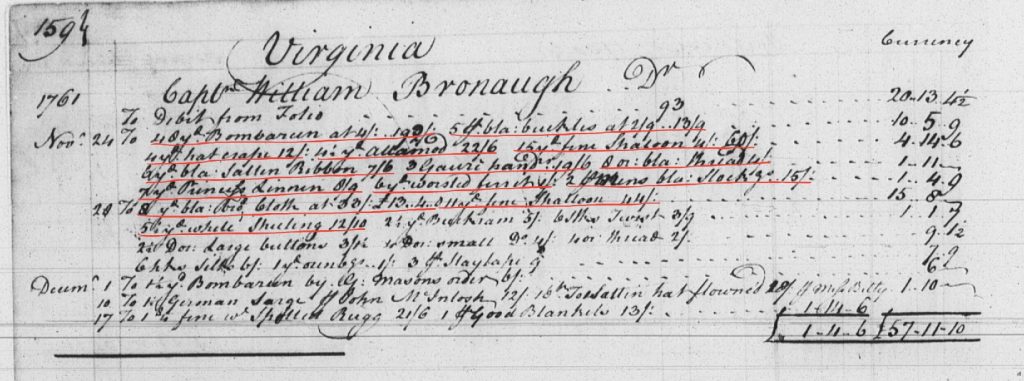

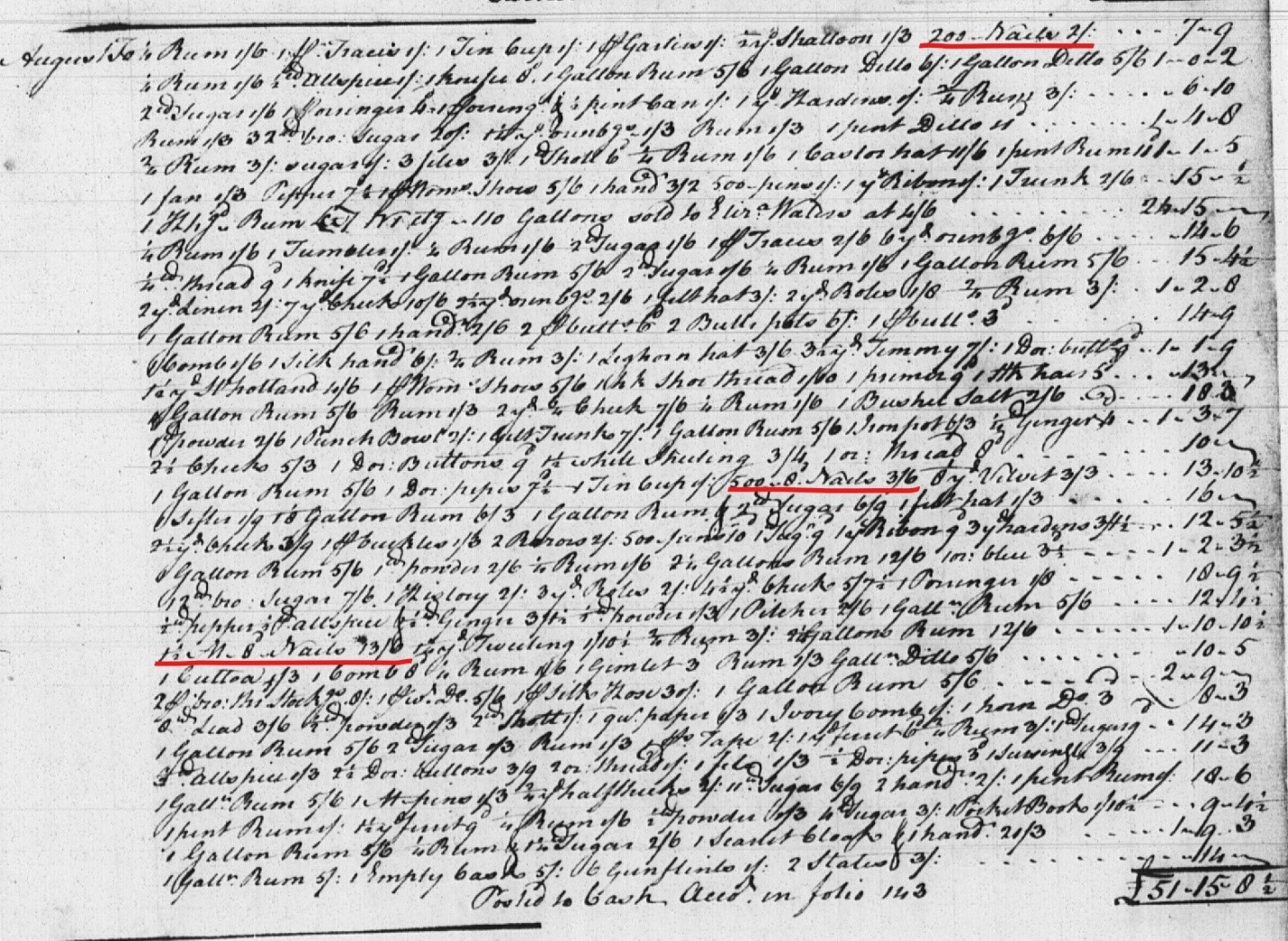

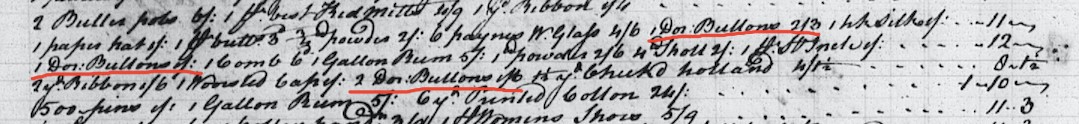

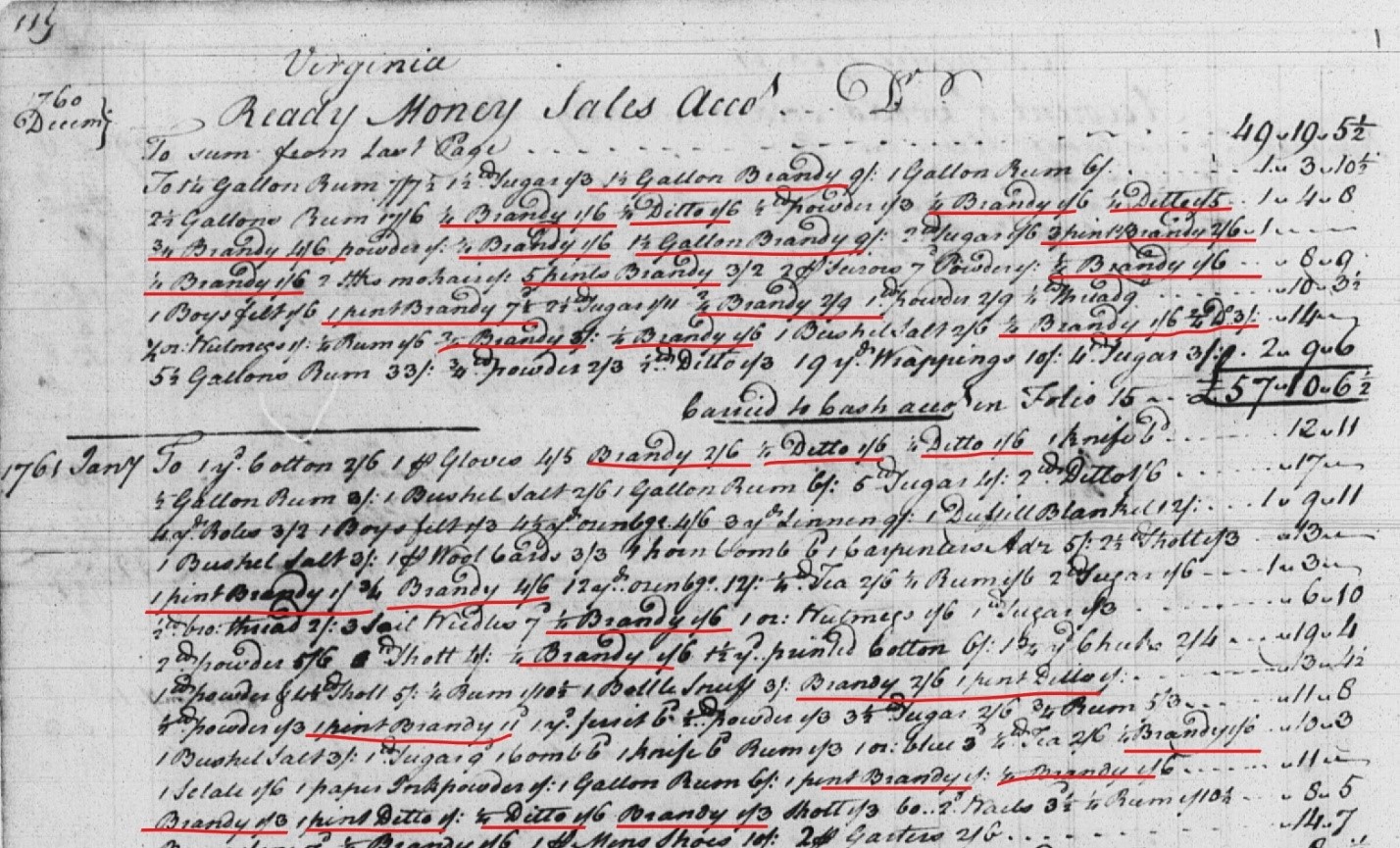

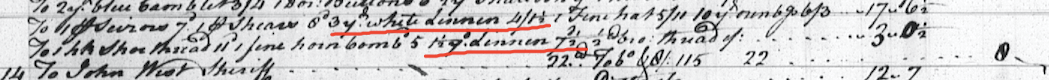

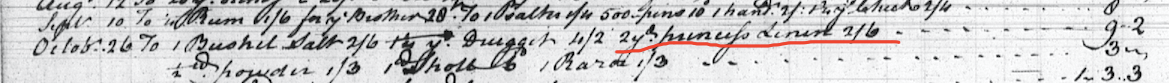

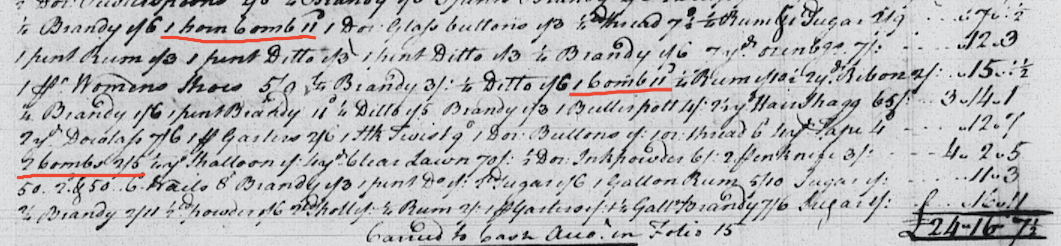

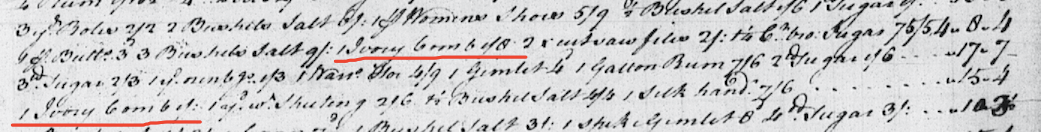

Evidence: In the ledger, William Haden purchased “1 pint Glass Decanter” in 1761.[9] A decanter is “a bottle of…cut glass, with a stopper, in which wine is brought to the table, and from which the glasses are filled.”[10] The question that rose from these findings was: Where did this glass come from? Henderson ordered various glass instruments from Glasgow, Scotland, including 2 dozen pint glass decanters, 2 dozen quart glass decanters, and looking glasses.[11] From this, it appears that glass production in Scotland may have been more successful than colonial production.

The Northern Attempt: In 1739, Caspar Wistar, a brass button entrepreneur from Germany, travelled to Pennsylvania and established a glass factory in Alloway, New Jersey. Wistar and his son, Richard, used two furnaces, two flattening ovens, several pottery mills, and a cutting house to operate their factory for forty years.[12] Wistar’s glassmaking venture became the first successful glassmaking factory in America. Besides his massive production of bottles, he also began to produce window glass. In addition to his production of Waldglass (green-yellowish color) style items like bottles, Wistar added the production of a clearer colored glass to his body of work.[13]

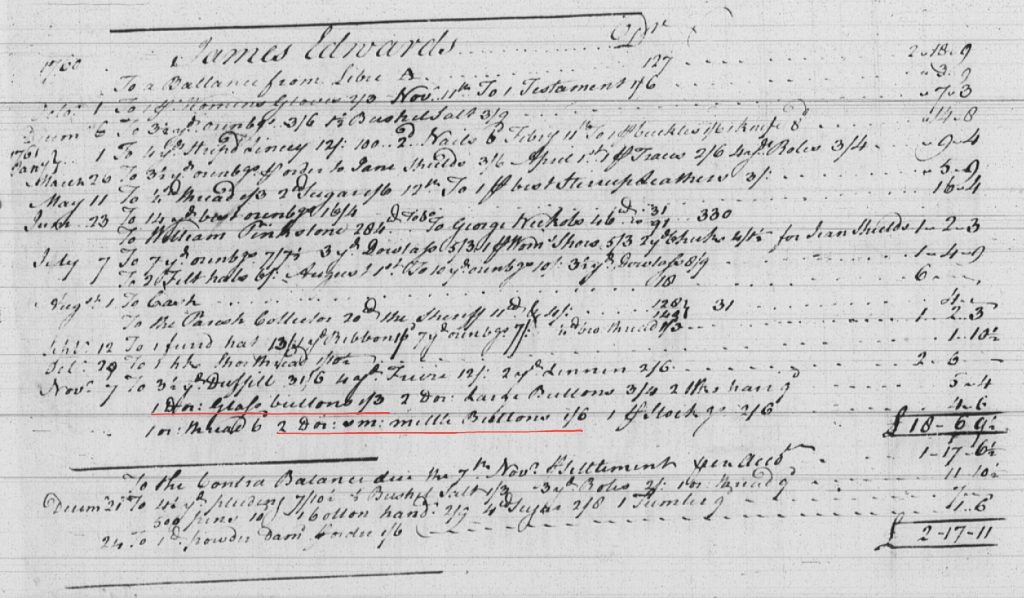

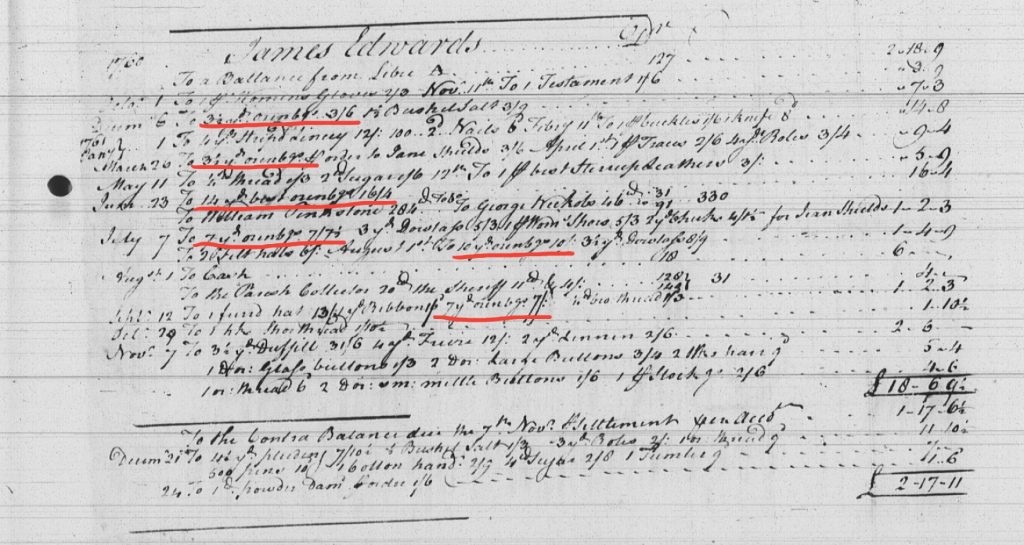

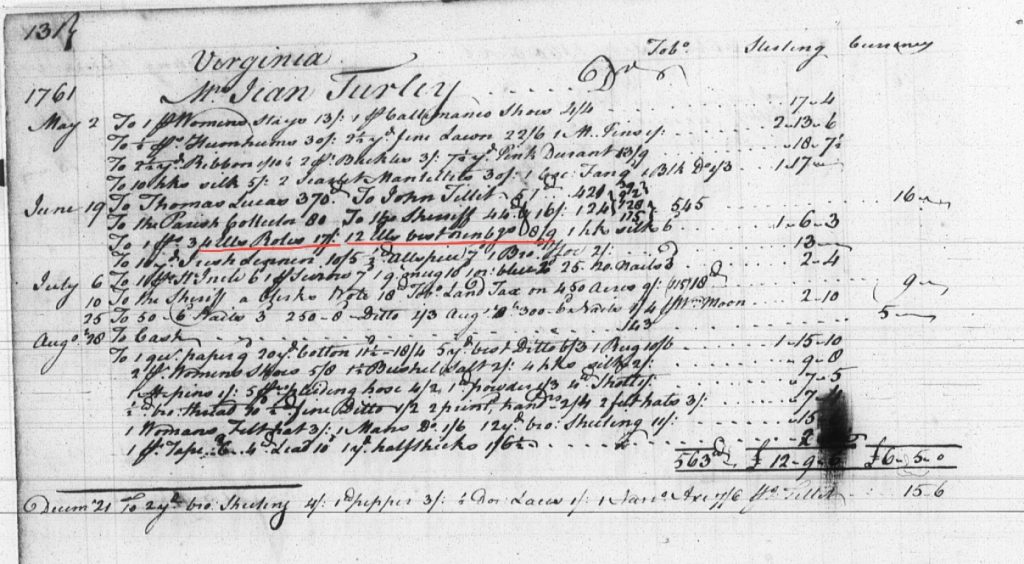

Making Connections: Though Wistar was extremely successful in his brass button making business – it is said to have totaled almost 700 pounds at his death – and though he had success in making window glass and bottles, there were other forms of glass making that he did not venture into.[14] One of these was glass buttons. According to one of the accounts from Colchester, in November, 1761, James Edwards bought a dozen glass buttons along with 2 dozen “mettle” buttons. Purchasing both types of buttons may have meant Mr. Edwards had a higher social standing. The glass buttons were more expensive than the metal ones by half a shilling or six pence.[15]

Much like it is today, glass in the eighteenth century was a versatile material, able to craft a variety of goods. Though some manufactures, such as window glass, were relatively inexpensive to buy, others, such as decanters, drinking vessels, and buttons, seem to be more reflective of a higher social standing.[16] The availability of these goods at the Colchester store in 1760-1761 stands as a testament to the materialism that would shape colonial identity for years to come.

[1] National Park Service, “Jamestown Glasshouse,” Historic Jamestowne: Glasshouse, last modified April 12, 2012, accessed March 23, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/jame/planyourvisit/glasshouse.htm.

[2] NPS, “Glasshouse.”

[3] NPS, “Glassmaking at Jamestown,” Historic Jamestowne, last modified February 26, 2015, accessed May 25, 2018, https://www.nps.gov/jame/historyculture/glassmaking-at-jamestown.htm

[4] Alan Taylor, “Virginia, 1570-1650”, in American Colonies: The Settling of North America (New York: Penguin Books, 2001), 130.

[5] NPS, “Glassmaking.”

[6] Ibid.

[7] Thomas L. Purvis, Colonial America to 1763, Almanacs of American Life (New York: Facts on File, 1999), 107.

[8] Purvis, Colonial America, 107.

[9] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 111 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[10] “decanter, n.,” OED Online (Oxford University Press) http://www.oed.com/ezproxy.net.ucf.edu/view/Entry/48019?rskey=upZsGT&result=1&isAdvanced=false, accessed May 25, 2018.

[11] Alexander Henderson, Charles Hamrick, and Virginia Hamrick, Virginia Merchants: Alexander Henderson, Factor for John Glassford at His Colchester Store, Fairfax County, Virginia, His Letter Book of 1758-1765 (Athens, Ga: Iberian Pub. Co, 1999).

[12] Purvis, Colonial America, 107.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Insa Kummer, “Caspar Wistar established the first successful glass manufacturing business in North America,” Immigrant Entrepreneurship, last modified September 25, 2014, accessed May 25, 2018, https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entry.php?rec=1.

[15] Henderson, et. al. Ledger, 1760-1761 folio 19 Debit.

[16] David Dungworth, “The Value of Historic Window Glass,” The Historic Environment: Policy and Practice 2, No. 1 (June 2011): 41, DOI 10.1179/175675011X12943261434567.

Nails being made at the blacksmith shop at Colonial Williamsburg in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Nails being made at the blacksmith shop at Colonial Williamsburg in Williamsburg, Virginia.

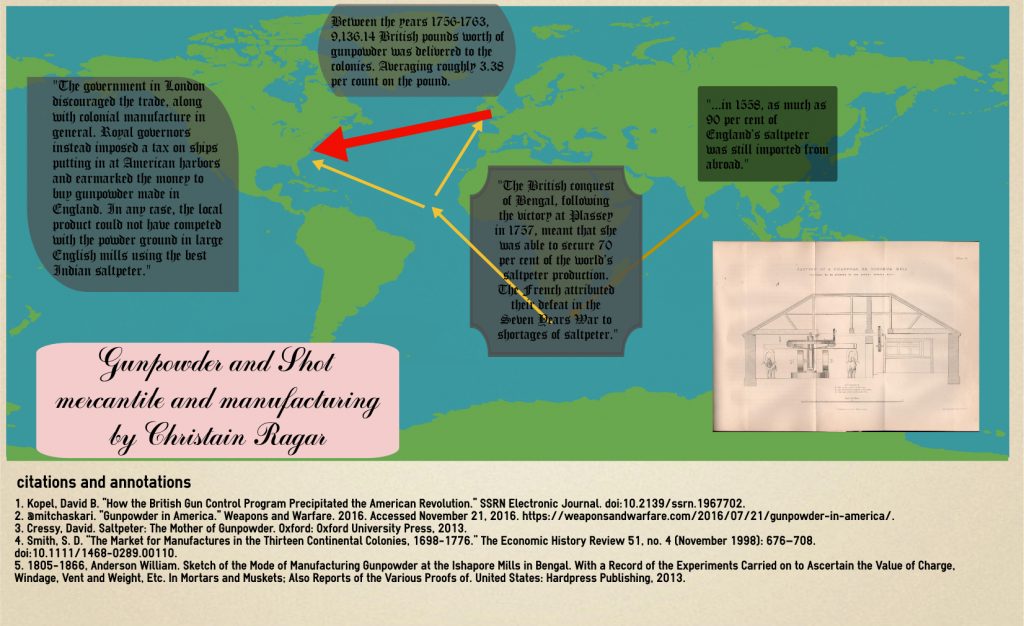

Infographic on Shot

Infographic on Shot