Jason Bernstein // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

Whenever we look back on the colonial period of American history, we always look to the relationships amongst the Native Americans, the colonial economy, and the events leading up to the American Revolution. But there are several aspects that go under the radar, such as diet, climate, and family life. One aspect of family life is how the family dressed themselves. And that’s where recognizing one of the period’s mainstay fabrics come in. Osnaburg, a common fabric during the 1600 and 1700s, found its way into the colonies through trade imports where it was utilized in many forms. I will focus on the creation of this fabric, its uses, and its representation of colonial wealth during the eighteenth century.

Osnaburg originated in Germany before being exported to England and later, her colonies. Woven from flax and hemp, it naturally looked brown due to weavers not bleaching it during its fabrication.[1] Eventually, Scotland began weaving this cloth to compete with other markets, and saw much exportation to the colonies.[2]

Osnaburg, a rough-textured cloth, was also very durable. As such, it was used for food sacks, and other assorted bags to transfer objects. However, its primary use was in clothing, particularly for slaves on plantations.[3] As an example in 1705, the Virginian government consolidated the different laws regarding slaves and indentured servants. Among them, one law stated that slaves had to be clothed, with no other clarifications or restrictions about the clothes, “That all masters and owners of servants, shall find and provide for their servants wholesome and competent diet, clothing, and lodging…”[4] This led many slave owners to provision their enslaved with clothing that was readily available, as well as both time and cost effective. In addition to its availability and affordability, osnaburg fabric for enslaved clothing was favored for its simple construction and hardiness.[5]

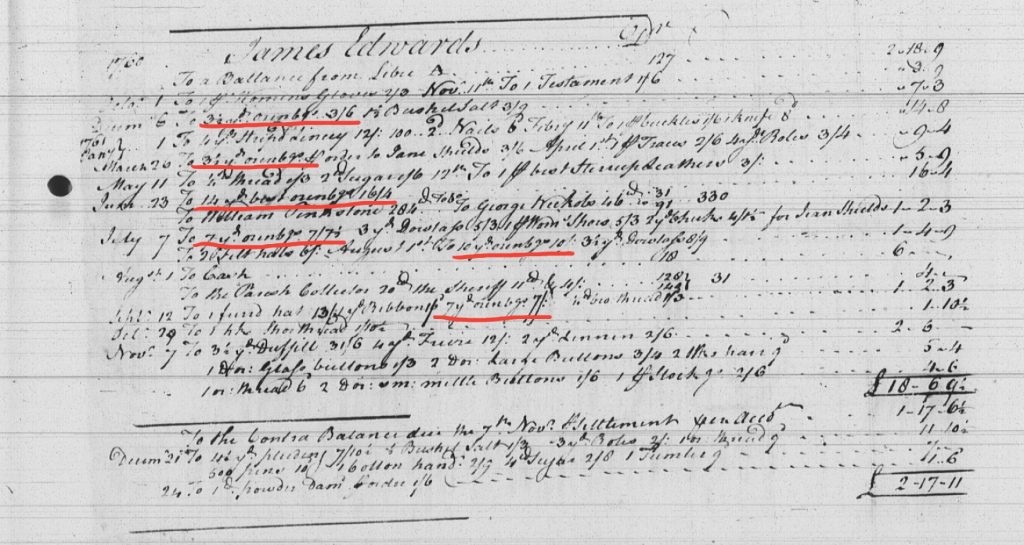

The amounts of osnaburg fabric purchased depended on the wealth of the consumer, and that can give us an idea of its intended use. For example, let’s examine the ledger account for James Edwards, a customer of Glassford and Henderson’s store in Colchester, Virginia, from 1760-1761. Over eleven months, he purchased thirty-one yards of osnaburg, with the cost of each purchase averaging one shilling per yard; he also purchased fourteen yards of the best osnaburg available for a total of sixteen shillings and four pence.[6]

What could these amounts of osnaburg been used for? We can create an idea, by looking at the rest of his purchases. Metal and glass buttons, thread, nails, and pins point to clothing fabrication.[7] Five and a half yards of the fabric would make two pairs of men’s pants, while two and a half yards would make one woman’s petticoat. Osnaburg could also have been used to make work shirts. (Other fabrics, such as cotton, shirting, and linsey would have been used to make shirts as well, along with dresses and slips.)[8] The osnaburg could also have been used as a bag for nails (you wouldn’t want a flimsy bag holding them). We know that osnaburg was inexpensive and capable of withstanding harsh and prolonged working conditions.[9] From the amount Edwards bought over the span of one year and the amount of tobacco Edwards paid for goods (two hogsheads totaling over 2000 pounds of tobacco), it’s possible that he was a slave-owner.[10] The purchases he made and how much he bought reflect his wealth, which we can understand through the purchase of a simple fabric.

As we look back on osnaburg—a pretty simple fabric that has survived into the modern age, although made with more modern methods—shows how much the past affects us today. The creation, use, and purchasing of this cloth have given us a small insight into the wealth, culture, and production methods of the 18th century.

[1] Katherine Egner Gruber, “Slave Clothing and Adornment in Virginia,” Encyclopedia Virginia, last modified February 4, 2016, accessed April 12, 2017,

http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Slave_Clothing_and_Adornment_in_Virginia.

[2] Alastair Durie, “Imitation in Scottish Eighteenth-Century Textiles: The Drive to Establish the Manufacture of Osnaburg Linen,” Journal of Design History 6, no. 2 (January 1993): 71.

[3] Gruber, “Slave Clothing.”

[4] William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619 (Philadelphia: R. & W. & G. Bartow, 1823), 3:448, accessed April 10, 2018, http://vagenweb.org/hening/vol03-25.htm.

[5] Gruber, “Slave Clothing.”

[6] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 19 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[7] Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761 folio 19 Debit.

[8] Michael Wayne, “Slavery,” in Death of an Overseer: Reopening a Murder Investigation from the Plantation South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 81, eBook Collection EBSCOhost, accessed April 12, 2018.

[9] Gruber, “Slave Clothing.”

[10] Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761 folio 19 Debit.