2024 Fieldwork

The Kurd Qaburstan Project made significant progress in studying the Middle Bronze Age (1800 B.C.) city. Fieldwork included excavations, intensive surface collection, and geophysical surveys. This year’s research focused on two main areas: the Lower Town East, home to a monumental palace, and the Northwest Neighborhoods, a residential city block.

Lower Town East Survey and Excavations

Before excavation began, the team gathered artifacts from the surface. The area was divided into 10 x 10 meter sections for detailed study. This preliminary work offered valuable clues about how the spaces were used, guiding the team’s excavations.

Excavations in the Lower Town East confirmed the presence of a large palace first suggested by findings in 2022.

Work in the southern sector uncovered well-preserved monumental mudbrick architecture in a 10 x 10 meter excavation (Figure 1). A massive central wall, nearly 4 meters wide, highlights the grand scale of the structure. Artifacts such as door and jar sealings, pot marks, and two cuneiform tablets highlight the palace’s role as an administrative hub.

In the northern sector, the researchers excavated more monumental mudbrick architecture filled with layers of rubble and destroyed pottery, a third tablet, and disarticulated human remains. The two 5 x 5 meter contexts hint at dramatic events, possibly evidence of ancient warfare recorded in ancient texts.

The three cuneiform tablets are significant finds. The first written documents from the Middle Bronze Age discovered on the Erbil plain underscore the site’s historical importance. In ancient Mesopotamia, people used a script called cuneiform to write on clay tablets in various local languages. While we know a great deal about the development of writing in southern Iraq, far less is known about literacy in northern Mesopotamian cities.

Currently, historians rely on records written by the city’s powerful rivals. Specialists are currently studying the recently discovered tablets, and we hope to uncover more documents that shed light on Qabra’s history from the perspective of its own people. These tablets could reveal important details about the city’s connections with its neighbors during the Middle Bronze Age. For example, studying names can provide clues about cultural identity, while word choice and writing styles may reflect regional dialects known from other archaeological sites.

Figure 1: Monumental mudbrick architecture in the southern sector of the lower town palace, view to the north.

Northwest Neighborhoods Survey and Excavations

As in the Lower Town East, the team performed a detailed surface collection in the residential area. Archaeologists gathered and recorded pottery and other artifacts scattered across the city block. This work provided important clues about how unexcavated areas might have been used and helped the team decide where to dig.

The pottery included everyday items like cups, plates, bowls, and storage jars. In some areas, the collections pointed to household waste, while other areas suggested industrial activity or communal storage. Some pottery was surprisingly well-decorated and carefully made, hinting that private wealth may have been more common than expected.

Informed by the survey, excavations focused on a city neighborhood. There, the team uncovered a well-preserved pebbled courtyard, a midden filled with pottery and tools (Figure 2), and signs of food preparation. Inside one home, food remains and household pottery provided an intimate glimpse into daily life.

Animal bones found with the pottery suggest that residents enjoyed a varied diet, including domesticated meat and wild game. This level of dietary diversity is unexpected for non-elite populations in Mesopotamian cities, based on limited current evidence.

These findings may challenge ideas about sharp divisions between elite and non-elite lifestyles in ancient cities. The material culture and dietary practices reflect a community where some people lived relatively well. Future research will focus on learning more about daily life in the Middle Bronze Age.

Figure 2: Excavation of a pottery midden in the Northwest Neighborhoods.

Geophysical Survey

Geophysical surveys expanded the team’s understanding of Kurd Qaburstan’s urban layout. They revealed dense residential architecture, with streets converging near a possible city gate. The studies also suggest a second monumental structure on the high mound (Figure 3). The newly discovered building is thought to be yet another Middle Bronze Age palace.

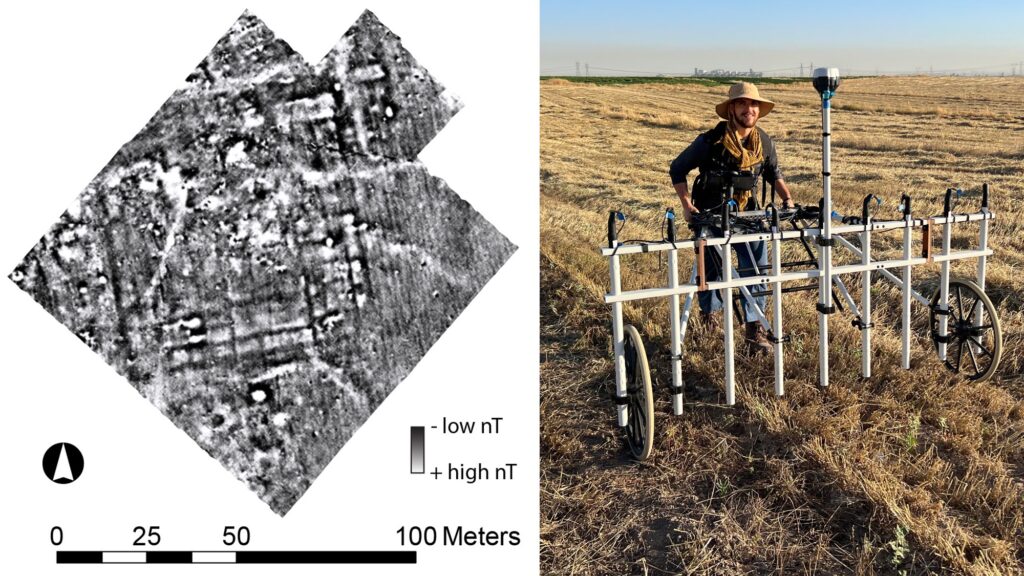

Non-destructive survey techniques have transformed archaeological research in recent decades. Scientific methods like magnetometry, ground-penetrating radar, and electrical resistivity allow researchers to see what lies beneath the surface without digging. These methods help preserve the site while providing clues about its layout and history. For example, magnetometry has revealed streets, houses, and even the foundations of monumental buildings, helping the team plan their excavations more effectively (Figure 4). This approach saves time, protects fragile sites, and opens up new ways to explore ancient cities.

Figure 4 (right): ASOR fellowship recipient Luke Poutre surveying the lower city with a SENSYS MXPDA magnetometer cart system.

Insights into an Ancient City

The findings from Lower Town East and Northwest Neighborhoods provide valuable insights into the city’s social organization and economic systems. The investigations of the elite administrative center and the everyday life of residents shed light on the city’s complex structure. The discovery of a second palace further emphasizes Kurd Qaburstan’s role as a major center of power during the Middle Bronze Age. These findings support the idea that Kurd Qaburstan is the ancient city of Qabra, a regional capital whose location was previously unknown.