Pvt. James Whitley (1924 – September 12, 1944)

4255th Quartermaster Truck Company

by Evan Murray and Kalynn Smith

Early Life

James Whitley was born in Orange County, FL, in late 1924 or early 1925. His parents, John and Rachel Whitley, were born in Georgia in 1887 and 1904, respectively. The couple moved to Florida sometime before 1924, where they raised James and his brother, Theodore Whitley.1 Their last recorded address was a segregated apartment complex at 1214H East South Street in either Winter Park or Orlando. It is not clear whether the family lived in Winter Park or Orlando as both cities at the time had poor, African-American communities that provided much of the cheap labor for the surrounding area. Whitley’s father worked as a laborer and his mother worked as a laundress.2

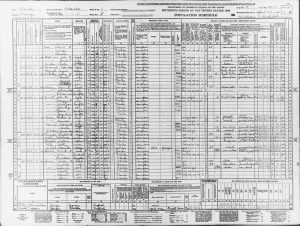

Whitley left school after the third grade. He either had no opportunities to finish his education as a result of segregation, or he had to leave school to help his father with work. The 1940 US Census states that John and James had been unemployed for some time, indicating that they struggled to find regular employment. The ability of the Whitleys, and of many other African-American families of the time, to find decent work in the job market was hindered by both institutionalized and informal racism that prevented non-whites from obtaining any economic independence that would better their position in society. James Whitley likely had to help the family earn enough money to survive given the deprivation they faced. Neither James nor his brother, Theodore, had known spouses or children, bringing an end to their family lines.3

Military Service

Whitley was drafted into the US Army on February 9, 1943: his service number was 34543070.4 As a private in the 4255th Quartermaster Truck Company — a segregated African-American unit — Whitley was responsible for creating and maintaining supply lines to frontline units. African-American units existed separately from white units and were exclusively support-oriented. This was a result of the prejudices held by military leaders at the time. They were hesitant to trust African Americans with frontline roles that required them to bare arms and competently follow orders.5

After his enlistment, Whitley went to Camp Blanding, near Starke, for training before deployment to the Western Front.6 His company was stationed in Tytherley Village in Hampshire, England, on June 30, 1944. It managed the flow of supplies to and from France, following the D-Day invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944.7 Whitley’s company eventually went to France, where he died in a car crash on September 12, 1944.8 Although he died in the line of duty, Whitley did not receive a Purple Heart for his service, because, like many African Americans, he was not part of a combat unit and thus the army considered his death as the result of a “non-battle injury.”9 As a participant of the overseas campaign, however, Whitely was awarded an American Campaign Medal and a World War II Victory Medal.

1 “U.S. World War II Army Enlistment Records,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KMVK-BW1: accessed October 20, 2015), entry for James Whitley.

2 “1940 United States Census,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VTC4-NZK: accessed October 20, 2015), entry for James Whitley, Orlando, Orange County, Florida.

3 Ibid.

4 “James Whitley,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed October 6, 2015, https://abmc.gov/decedent-search/whitley%3Djames-0; “World War II Army Enlistment Records,” entry for Whitley.

5 Phil Grinton, “Black Army/Air Corps Units Stationed in the United Kingdom,” Lest We Forget: African-American Military History by Historian, Author, and Veteran Bennie McRae, Jr. accessed October 20, 2015, http://lestweforget.hamptonu.edu/page.cfm?uuid=9FEC3368-DBFD-5737-1E9DEC0EFF8949A5.

6 “World War II Army Enlistment Records,” entry for Whitley.

7 Grinton, “Black Army/Air Corps Units.”

8 “U.S. World War II Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 9, 2021), entry for James Whitley.

9 Ibid; “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 9, 2021), entry for James Whitley.