1st Lt. William Wirt Webb (October 5, 1910 – August 15, 1944)

59th Armed FA Battalion

by Anthony Fair and Elizabeth Klements

Early Life

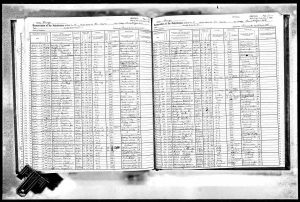

Born in Chicago, IL, on October 5, 1910, William Wirt Webb was the second child of Evelyn née Grossenbacher and William Warren Webb. At the time, William Warren worked as an office manager in the mail order industry and Evelyn took care of her family, which included William Jr. and his older sister Marjorie (1907).1 By 1915, the family of four moved to Brooklyn, NY, likely for a job opportunity, as William Warren became a superintendent for a mail order company. They settled in a rented home on East 12th Street between Prospect and Marine Parks.2 Both children attended school into their late teens and graduated with a grammar-school education.3 By 1925, the Webb family moved to East 32nd Street between Tilden Avenue and Beverley Road, and William Warren started his own food business. As seen in this 1925 state census, his wife and daughter worked for him, Evelyn as a saleslady and Marjorie filling cans, while William Jr. remained in school a few years longer.4

Sometime between 1925 and 1930, the Webb family moved to Jacksonville, Florida.5 Florida grew exponentially throughout the 1920s, and Jacksonville had nearly tripled in population during the decade.6 It was much smaller than the boroughs of New York, but it became the Webb family’s new home all the same. The family rented a modest house at 1905 Perry Place in South Jacksonville.7 William Warren may have moved his family for financial reasons, or because he wanted to be closer to his extended family.8 His own father, a retired Army Major and veteran of the Civil War, moved his family from New York to Mandarin in the late 1870s, where he established a farm on about thirty acres of land on the east bank of the St. Johns River. Major Webb and his family cultivated oranges, strawberries, and seasonal produce which they shipped north on steamships, using a dock that Major built on the St. John’s River. Major Webb was known and respected throughout the local community.9 He died in 1893 at the early age of fifty-five.10 His wife Clara and their three children – Wirt, Daisey, and William Warren – were left to look after the farm. This proved to be a struggle over the next nine years. In 1902 the family was forced to forfeit the farm for non-payment of taxes. Clara died in 1904. That same year William Warren married Evelyn in Chicago. Wirt moved on, presumably out of Florida. Daisey married, had children, and stayed in the Mandarin area. She was still living in Mandarin when William Warren moved his family to Jacksonville.11

William Jr. was in his late teens when the family moved to Jacksonville. His father became a watchman for a Shell Oil distribution plant, and, by the age of twenty, William Jr. found work as an electrician for Western Electric. Sometime between 1930 and 1935, William Jr. entered the new and burgeoning automobile industry, working on the sales floor of the Chevrolet Motor Division.12 In his early adulthood, he continued to live with his parents in Jacksonville, where he attended church at All Saints’ Episcopal Church. He was an active member of this community – he served as scoutmaster for the local Sea Scouts and for his church’s Boy Scouts troop.13 In 1937, his mother Evelyn Webb passed away at the age of fifty-five, and by 1940, William Jr. moved to Middlesboro, KY, likely for his job, as he remained a Chevrolet employee.14

Military Service

In 1940, the US ordered its first ever peacetime draft, in anticipation of the war to come. William Jr. registered for the draft in 1940 but was not selected.15 By March 1942, he returned to Florida where he applied to join the US Army as a warrant officer, at the age of thirty-two.16 The Webb family had an Army tradition. William’s grandfather served in the Civil War and his father in the Spanish American War.17 William did not have the level of education required for a commissioned officer, but his age, race, and work experience likely helped him earn a spot in the forty-first class of the Field Artillery Officer Candidate School at Fort Sill, OK. He graduated from the twelve-week course in December 1942 and became a 2nd Lieutenant in the 59th Armored Field Artillery Battalion.18 The 59th was one of three armored field artillery battalions attached to the 6th Field Artillery Group of the 5th Army. The unconventional structure of the 6th Field Artillery Group gave the commanders the freedom to attach the different artillery battalions to different Corps. The 5th Army consisted of three Corps: the II, VI, and the British X Corps. The 59th helped each of these corps on different occasions.19

The 59th Battalion utilized the M7 tank, which carried a 105mm howitzer that could send a hundred-pound shell up to seven miles. The M7 also had a “pulpit-like machine-gun ring” on the right side of the vehicle as a secondary weapon, which earned it the nickname “Priest.” The M7 carried seven soldiers, including a commander. There were four “Priests” per firing battery, and three batteries per battalion.20 When firing upon a target, a forward observer directed the battery. William, as an officer, would have accompanied his armored artillery crew as their commander most of the time. If the infantry needed to shell a specific target, however, a forward observer from the artillery would accompany them. The forward observer would go to the front and determine the location of the target and relay the position to the artillery. William acted as a forward observer near the front at the time of his death in August 1944.21

One year prior to this, William traveled with the 59th across the Atlantic Ocean, arriving in Oran, Algeria, on September 2, 1943, where they trained for a month before joining the Allied invasion of Italy. Although the Italian state surrendered after the Allies took Sicily, the German troops in Italy remained to fight. They created a series of defensive lines across the peninsula to keep the Allies pinned down in southern Italy, and the Allies decided to bypass these defenses with an amphibious attack on the coast, just south of Rome. Operation Avalanche, as it was known, began on September 9, 1943, a few days after the 59th reached Algeria. The Allies successfully established a beachhead at Salerno and Naples, but the fighting took long enough that German forces had a chance to strengthen their defenses in the mountains between Salerno and Rome. The Allies’ next objective was to break through these defenses, collectively known as the Winter Line, and reach Rome.22

The 59th joined the action at the end of October when they landed in the newly Allied-controlled port of Naples. The US army attached the 59th to the British X Corps Artillery, which sent the 59th to help the 56th Infantry pursue the retreating German army and secure a defensive position along the Winter Line about forty miles north of Naples. By mid-November, the 59th returned to the Naples area to prepare for their next engagement. In December, the X Corps ordered the 59th to support the 46th Division’s attack on Mount Camino, one of the Germans’ main defenses on the road to Rome. This was part of a broader assault on the Winter Line known as Operation Raincoat. The 59th’s primary task was to lay cover fire for the infantry troops who successfully took Mount Camino by Christmas.23

The 5th Army’s next goal was to capture the German-held monastery of Cassino, which was the Allies’ key to breaking through the Winter Line. The US army leadership reassigned the 59th to the II Corps and then to the New Zealand Corps to participate in this attack.24 The battle for Cassino was long and difficult, and the Allies’ eventual success in March 1944 depended heavily on the participation of Polish forces and British troops from Canada, New Zealand, and India, with whom the 59th fought. After taking Cassino, the 59th had a month to rest and train before the next big attack.25 In May 1944, the Allies began their push to Rome. In this campaign, the 59th supported the First Special Service Force, an elite group of Canadians and Americans trained for combat in mountains and in the air. They triumphantly entered Rome on June 4, but only had a few days to rest before their next assignment.26

On June 10, the US army command assigned the 59th to the IV Corps, which moved into northern Italy in pursuit of retreating German forces. The fighting was harsh, and they advanced slowly, reaching the Cecina valley by early July. Although the fighting in Italy was not done, the capture of Rome meant that the Allies could divert manpower in Italy to the invasion of southern France, known as Operation Dragoon. In July 1944, the Army command reassigned the 59th to the 45th Division of the US 7th Army and sent them to Naples to prepare for the imminent attack.27

The Operation Dragoon landings took place on France’s southern coast, at several locations along the Cote d’Azur, which began on the morning of August 15, 1944. William and the 59th landed at the seaside town of St. Maxime, leading the 45th Division. They did not encounter much resistance; German forces were spread thin across the landing zone and German leaders believed that the attacks would take place at bigger port cities on the coast.28 Nevertheless, the Allies lost about one hundred men on the first day, including William. 1st Lt. William Webb was acting as a forward observer with a rifle company when the company came under enemy fire. As shells rained around him, he attempted to radio for artillery fire on the hostile positions when a fatal bullet struck him in the neck and killed him. He was thirty-three years old.29

Legacy

After Operation Dragoon, William’s battalion helped the Allied forces push north toward the German border, liberating France town by town. In late November 1944, they helped capture the city of Strasbourg, in Alsace, and then supported the Allies’ efforts to breach the Siegfried Line throughout the winter of 1944 – 1945. In March 1945, the 59th crossed the Rhine and moved south through Germany, reaching the city of Oberammergau in Bavaria when Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945.30

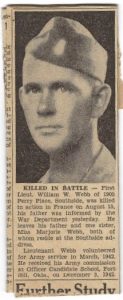

As recorded in this local newspaper article, the US Army posthumously awarded 1st Lt. Webb a Purple Heart for his death in the line of duty and a Silver Star for the gallantry and courage he displayed in his last moments. William Warren received Lt. Webb’s medals on his behalf and died shortly after his son, on March 21, 1945, at the age of seventy-three.31 By the end of the war, Marjorie Webb remained the only living member of the Webb family: she never married and passed away in 1970 at the age of sixty-two.32 The US Army buried Lt. Webb at the Rhone American Cemetery in eastern France, and his family created a memorial stone for him at the family plot in the Mandarin cemetery.33 Even though William is buried abroad, he is remembered with the rest of his Florida family by the bank of the St. Johns River.

1 “1910 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 14, 2021), entry for William Webb, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois; “Cook County, Illinois, Birth Certificates Index,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 14, 2021), entry for William Wirt Webb.

2 “1915 State Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 14, 2021), entry for W.W. Webb, Brooklyn, Kings County, New York; “1920 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 14, 2021), entry for William Webb, Brooklyn, Kings County, New York.

3 “1925 State Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 14, 2021), entry for William Webb, Brooklyn, Kings County, New York; “1930 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 14, 2021), entry for William and Marjorie Webb, Jacksonville, Duval County, Florida.

4 “1925 State Census.”

5 “1930 US Census.”

6 Gary R. Mormino, “Twentieth-Century Florida: A Bibliographic Essay,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 95, no. 3 (2017): 295.

7 “1930 US Census.”

8 “Other Notable Residents: William Webb,” Mandarin Museum & Historical Society, accessed August 14, 2021, https://www.mandarinmuseum.net/mandarin-history/notable-residents. Many thanks to Sandy Arpen from the Mandarin Museum for providing us with information on 1st Lt. Webb and his family.

9 “Other Notable Residents: William Webb.”

10 “William Wirt Web,” Find a Grave, accessed August 8, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/75847928/william-wirt-webb; “1885 State Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 15, 2021), entry for W.W. Webb, Mandarin, Duval County, Florida.

11 Bob Nay, “I Am A Full-Fledged Floridian Now:” The Life and Times of William Wirt Webb of Mandarin, Florida (Jacksonville: Mandarin Museum & Historical Society, 2015).

12 “1930 US Census;” “1935 State Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 23, 2021), entry for William W. Webb Sr. and Jr., Duval County, Florida; “1940 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed January 19, 2022), entry for William Warren Webb; “U.S., World War II Draft Registration,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 23, 2021), entry for William Wirt Webb, serial number 2256.

13 “Father Given Dead Officer’s Army Medal,” Florida Times-Union, article clipping provided by the Mandarin Museum & Historical Society, https://projects.cah.ucf.edu/fl-francesoldierstories/wp-content/uploads/Webb-article-2.jpg.

14 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards;” “Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed January 19, 2022), entry for Evelyn Webb.

15 Ibid.

16 “U.S., Army Enlistment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 23, 2021), entry for William W. Webb, service number 14081383. Service numbers beginning in 1 indicate that the soldier voluntarily enlisted.

17 “Other Notable Residents: William Webb;” “1930 US Census,” entry for William W. Webb (Sr.).

18 “Class Rosters 1940s,” Artillery OCS Alumni, https://www.artilleryocsalumni.com/rosters/classrosters40s.pdf, 58; “Headstone Inscription and Internment Record,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed August 23, 2021), entry for William W. Webb, service number 01174469. A soldier’s service number changes when he becomes an officer.

19 Lewis J. Gorin Jr., The Cannon’s Mouth: The Role of U.S. Artillery during World War II (New York: Carlton Press, Inc., 1973), 1 – 14.

20 William G. Dennis, “U.S. and German Field Artillery in World War II: A Comparison,” National Museum of the United States Army, accessed August 23, 2021, https://armyhistory.org/u-s-and-german-field-artillery-in-world-war-ii-a-comparison/.

21 Gorin, 55 – 57; “Father Given Dead Officer’s Army Metals.”

22 Col. Kenneth V. Smith, “Naples-Foggia,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, https://history.army.mil/html/books/072/72-17/CMH_Pub_72-17.pdf.

23 Gorin, 64 – 74, 80 – 86; Fifth Army Historical Section, Fifth Army at the Winter Line (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 1990), 15 – 28.

24 The New Zealand Corps at this time included the New Zealand Infantry Division and the 4th Indian Division. See “The Italian Campaign: Cassino,” New Zealand History, accessed April 21, 2022, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/the-italian-campaign/cassino.

25 Gorin, 88 – 99; “Battle of Monte Cassino,” fabr245.org, accessed January 20, 2022, http://frabr245.org/Mil%20Hist%20-%20WWII%20Battle%20of%20Monte%20Cassino.pdf.

26 Gorin, 100 – 121.

27 Ibid, 120 – 121.

28 Ibid, 122 – 127; Jeffrey J. Clarke, “Southern France,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, https://history.army.mil/html/books/072/72-31/CMH_Pub_72-31(75th-Anniversary).pdf.

29 “Father Given Dead Officer’s Army Medal;” “U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed January 20, 2022), entry for serial number O1174469. The newspaper article mistakenly cites Webb’s death as October 15.

30 Gorin, 140 – 255.

31 “Father Given Dead Officer’s Army Medal;” “Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed January 20, 2022), entry for William Warren Webb.

32 “Alabama, U.S., Deaths and Burials Index, 1881-1974,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed January 20, 2022), entry for Marjorie Leona Webb.

33 “William W. Webb,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed January 20, 2022, https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/webb%3Dwilliam-3; “Lieut. William Wirt Webb,” Find a Grave, accessed January 20, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9999501/william-wirt-webb.