2nd Lt. Connie O. Walker (December 31, 1920 – August 14, 1944)

856th Bombardment Squadron, 492nd Bombardment Group

by Luke Craig

Early Life

Connie O’Donald Walker Jr.’s parents, Lennie May Lee and Connie O’Donald Walker Sr., were born in Georgia and Florida, respectively.1 Walker Sr. grew up in Kings Ferry, FL, and served in the US Navy in World War I as a Seaman, 2nd Class.2 After the war, he moved to Waycross, GA, and lived in a multigenerational home, with his grandmother Susan F. Mott, his mother Jinnie, and his aunts and uncles.3 Walker Sr. met Lennie in Georgia and they married on March 5, 1920.4 On December 31, Walker Jr. was born.5 He was the oldest child, with three siblings: Loinys (1924), Ruth (1927), and Hampton (1930). When his parents married, Connie’s father, Walker Sr. was a salesman at a dry goods store. By 1930, the family owned their own house in Waycross and Walker Sr. ran a grocery store, allowing his wife to stay home, and his children to attend school without interruption.6

Between 1930 and 1940, Walker Sr. moved his family to Tampa, FL. It is possible that he lost his grocery store in Waycross, due to the economic difficulties of the Great Depression, and moved to Florida for a fresh start. Walker Sr. may have had contacts in Florida through his family or heard about job opportunities in the port city. Both he and Walker Jr., who graduated from high school in Waycross, found employment at the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company as meat cutters.7 The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company was the largest grocery store in the United States at the time.8

Military Service

In February 1942, both Walker Jr. and Sr. registered for the draft. Walker Sr. registered for the “Old Man’s Draft,” which the Federal Government used to keep track of men ages forty-five to sixty-five, in case they could serve the war effort on the home front.9 Walker Jr., age twenty-one, registered for the regular “Young Men’s Draft,” and, seven months later, applied to the US Air Force’s Aviation Cadet training program.10 Created as a way to quickly train pilots for the war effort, the Aviation Cadet program was highly selective, putting its applicants through a series of physical, psychological, and intelligence tests.11 Walker Jr. successfully passed this screening process and began training at the Advanced Twin Engine Flying School in Blytheville, AK in March 1943. About a year later, he graduated and entered the Air Force as a 2nd Lieutenant.12

After earning his wings on January 7, 1944, Walker Jr. returned to Tampa, FL, and married a Tampa native, Lucille Thomasine Parks, a few weeks later. The newlyweds then moved to Salt Lake City, UT where Walker Jr. was stationed.13 In June of 1944, the Air Force sent Walker Jr. to Harrington, England.14 There, he joined the 801st Bombardment Group, which became the 492nd Bombardment Group under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Fish. While in England, Walker Jr. most likely trained with the Royal Air Force (RAF) as did most of the members of the 492nd.15

In the 492nd, Walker Jr. served as a co-pilot for 2nd Lieutenant Richard Norton in a B-24 plane named Lynn Bari II.16 Lynn Bari, an actress known for being the seductive man-killer in movies, earned the second spot on a survey servicemen took in the 1940s on the most popular pin-up models; second to Betty Grable.17 The Lynn Bari II had an eight-man crew, seen in this photo taken in New York before the men shipped out. The Norton Crew, as they were known, included Llyod L. Anderson, the navigator, Benjamin Rosen, the bombardier, John Gillikin and James H. Husbands, engineers, William Moncy, the radio operator and Wayman Skadden, the gunner.18 At the Harrington base, the Norton Crew participated in Operation Carpetbagger, the Allied mission to airdrop supplies to the Maquis in German-occupied Vichy France.19

The Maquis, an element of the decentralized French Resistance, was made up of French citizens selected for ‘voluntary’ work in German munitions factories, as part of ever rising labor quotas the Nazis sent the Vichy regime to ensure Germany met its ever increasing need throughout the war. While Vichy propaganda tried to frame it as voluntary service in the shared fight against the Bolsheviks, many selected as ‘volunteers’ preferred fleeing into the hills and mountains of southern France than performing slave labor in Germany.20 The Maquis got their name from the bushes or thickets found in the hills of southern France where these resistance fighters lived and fought.21 The Operation Carpetbagger planes dropped cylinders filled with weapons, ammunition, and other supplies including bicycles, which played a vital role in communication. On their return to England, the Allies often dropped propaganda leaflets encouraging the French to resist.22

The Allied nighttime missions to support the French Resistance were extremely dangerous and required skilled pilots. Support teams heavily modified the B-24 Liberators, painting them black so they would be nearly invisible, even when the Germans used searchlights, and gutting the interior so that they could hold both the crew and all the supplies they were dropping.23 The crew could not see their drop sites in the dark. As a result, the Allies and the Resistance developed a radar system called the Rebecca/Eureka transmitter-receiver set. The pilot had a “Rebecca” transmitter that communicated with the “Eureka” receiver, which the Maquis hid at the drop site. The pilot used the Eureka’s response to find the drop zone at night.24 Colonel Clifford Heflin, the commanding officer of Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Fish, remarked that “it takes a lot of training and flying ability to hit a drop zone right on the nose. The best pilots for the job are those who have been on anti-submarine patrol.”25 This gives us just some idea of how skilled Walker Jr. and Norton must have been as pilots since they were selected for these missions.

The Norton Crew flew eight such missions throughout July and August 1944 and became the first American pilots to reach the department of the Rhone, over four hundred miles from the English Channel.26 On August 14, 1944, the eve of Operation Dragoon – the Allied invasion of Southern France – the Norton Crew flew to a supply drop near the small town of Duerne, France, about twenty-five miles west of Lyon. Norton and Walker flew in way too low in total darkness across the hilly terrain. A Maquis Chief codenamed “Mary” yelled through the headset “Straighten up!” but it was too late. The Norton Crew crashed into a hill and the plane exploded. Walker Jr. and five of the Norton crew died on impact. William Moncy and John Gillikin, who had been thrown from the plane, suffered massive burns, but survived the initial crash. The Maquis rushed to the crash site searching for survivors. They found Moncy within hours, and Gillikin a day later. They sent both men for emergency treatment, but Moncy died from his injuries. The doctors at the time noted that his injuries were so extensive that “any treatment was hopeless.”27 Gillikin, whose face was so badly burned he initially needed to use his fingers to open his eyes, recovered with local farmers until the Maquis connected him to the Red Cross, making Gillikin the sole survivor of the Norton Crew.28

The Maquis also recovered the rest of the Norton Crew, wrapping their bodies in their parachutes, and hid them at a nearby farm until they could bury them. With the help of other locals, they worked overnight to build six caskets, and then transported the bodies to the nearby village of St. Martin-en-Haut. There, they held a church service and buried the Norton crew at the village cemetery, as well as two local Maquis who had died at German hands the day before. The Germans directly forbade such funerals, but, despite the threat of discovery by a nearby German garrison stationed, a very large crowd of villagers attended the ceremony to pay their respects to the deceased. The funeral took place on the very day that Allied forces landed on the coasts of southern France; this likely drew away the Germans’ attention, and emboldened the citizens of Duerne, St. Martin-en-Haut, and the nearby St. Symphorien-sur-Coise to publicly honor those who died for France’s freedom.29

Legacy

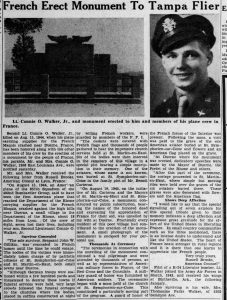

2nd Lt. Connie Walker’s death coincided with the Allied liberation of southern France. The Maquis who helped bury him immediately left to assist the Allies by sabotaging the German forces near the city of Lyon. A couple weeks later, Duerne and its neighbors were free from German occupation.30 Walker and the rest of the Norton crew’s sacrifice meant so much to these citizens that, a year after the crash, they built a monument to the crew. Despite the ravages of six years of war, and desperate poverty, the Maquis and French people in these small rural towns raised enough money to honor the men who died trying to help them defend themselves and their country. When the monument was unveiled on August 19, 1945, thousands of French citizens, American Forces, and the Red Cross participated in a dedication service.31 Russel Brooks, an American diplomat who attended the memorial, said:

I would like to say that the special signaling out of seven aviators for this tribute given to their memory indicates a deep affection and expresses great gratitude in the efforts of the United States in liberating France…the heart of France beats stronger in rural regions and it’s there that one learns to appreciate the French People.32

After the war ended, the US Army reburied Walker Jr. and his comrades at the Rhone American Cemetery, which began as a temporary cemetery for US soldiers killed in combat in August 1944 but became an official overseas American cemetery in 1956.33 It also posthumously awarded Walker Jr. an Air Medal and a Purple Heart for his service.34 He was survived by his parents, siblings, and his wife, Thomasine, who remarried a veteran named Aaron D. Blankenship in 1946.35 She passed away in 2004, at the age of seventy-nine.36

The people of France still honor the Norton crew. The monument appears on several websites, including directions to the crash site. In 1989, Gillikin returned to Duerne, forty-five years after the crash, to visit the monument and participate in the anniversary commemoration ceremony, along with the members of the Resistance who helped him to safety.37 In 2014, the citizens of the Duerne area held a seventieth anniversary commemoration of the crash. A large crowd gathered before the memorial, where the Mayor of Duerne read the names of the dead, and local notables reflected on the courage and sacrifices of those involved in the crash. The Deputy of Duerne emphasized the gratitude which “we owe to all these men committed to France’s liberty,” and Pierrot L’hopital de Saint-Symphorien, urged “history teachers…to tell this [story] to their students rather than the story of the pharaohs in Egypt.”38 After the speeches, the presentation of a wreath, and a moment of silence and patriotic songs, the crowd processed to the marker at the crash site where Walker Jr. and the six other Crew gave their lives for France’s liberty.39

1 “1930 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/21705298:6224: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for Connie and Lennie Walker, Waycross, Ware County, Georgia.

2 “Florida, World War I Navy Card Roster, 1917-1920,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS1B-79R2-S?cc=3010015: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for Connie Walker, serial number 162-53-45.

3 “1920 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for Connie Walker, Waycross, Ware County, Georgia.

4 “Georgia, U.S., Marriage Records From Select Counties, 1828-1978,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for Connie O’Donnell Walker and Lonnie May Lee.

5 “U.S., World War II Draft Registration,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for Connie O’Donell Walker Jr., serial number 317.

6 “1930 U.S Census.”

7 “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for Connie Walker, Tampa, Hillsborough County, Florida.

8 “Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, Inc: American Company,” Britannica, accessed April 28,2021. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Atlantic-and-Pacific-Tea-Company-Inc.

9 “U.S., World War II Draft Registration,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for Connie O’Donald Walker, serial number 1846; “The Old Man’s Draft,” Newberry, accessed July 21, 2012, https://www.newberry.org/old-mans-draft.

10 “With Our Boys On All Fronts,” The Tampa Times (Tampa, Florida), January 14, 1944, Newspapers.com.

11 Bruce Ashcroft, We Wanted Wings: A History of the Aviation Cadet Program (HQ AETC Office of History and Research, 2005), 33 – 34.

12 “Miss Thomasine Parks Bride of Lieutenant,” The Tampa Times (Tampa, Florida), January 21, 1944, Newspapers.com.

13 “Miss Thomasine Parks.”

14 “Tampa Pilot is Missing Over France,” The Tampa Tribune (Tampa, Florida), September 6, 1944, Newspapers.com; “Norton Crew,” The Wartime Experiences of Carpetbaggers, accessed April 28, 2021, http://www.801492.org/Air%20Crew/Norton/Norton%20Crew.html.

15 Don Holloway, “Brave B-24 Aircrews Smuggled Spies into Enemy Territory in Europe,” History Net, accessed April 29, 2021, https://www.historynet.com/brave-b-24-aircrews-smuggled-spies-into-enemy-territory-in-europe.htm.

16 “2Lt. Connie O’ Donald Walker Jr,” Find a Grave, accessed April 28, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56511412/connie-o’donald-walker.

17 “Lynn Bari Biography,” IMDb, accessed April 28, 2021, https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0054609/bio?ref_=nm_ql_1#trivia.

18 “Missing Air Crews Reports,” database, Fold3.com (https://familysearch.org/: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for aircraft 42-40172.

19 “Operation Carpetbagger,” National Museum of the United States Air Force, accessed April 28, 2021, https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/195994/operation-carpetbagger/.

20 Robert Gildea, Fighters in the Shadows: A New History of the French Resistance (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2015), 58 – 82.

21 C. Peter Chen, “The French Resistance 22 Jun 1940- 28 Aug 1944,” World War II Database, accessed April 28, 2021, https://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=153 .

22 Holloway, “Brave B-24 Aircrews.”

23 Holloway, “Brave B-24 Aircrews.”

24 “Radar Recollections – Rebecca/Eureka,” Centre for the History of Defense Electronics, accessed July 27, 2021, http://histru.bournemouth.ac.uk/Oral_History/Talking_About_Technology/radar_research/rebecca_eureka.html.

25 Holloway, “Brave B-24 Aircrews.”

26 “French Erect Monument To Tampa Flier,” The Tampa Tribune (Tampa, Florida), March 21, 1946, Newspapers.com ; « Norton Crew Mission Reports, » at « 36th/856th BSs Norton Crew, » The Wartime Expériences of the Carpetbaggers, accessed July 27, 2021, http://www.801492.org/Air%20Crew/Norton/Norton%20Crew.html.

27 “Nuit du 14 au 15 Aout à Duerne: Le crash du bombardier américain,” Le Coqpelaud de St-Sym no. 120 (August 2015): 3, http://lecoqpelaud.com/iphone-coq/nav/Par%20Annees/2015/coqpelaud120/CP120P3.pdf. We thank Marie Oury for her assistance in finding numerous French language sources that have helped us to tell the Norton Crew’s story.

28 Robert W. Fish, They Flew at Night: Memories of the 801st/492nd Bombardment Group (San Antonio: 801st/492nd Bombardment Group Association, 1990), 221 – 222; “American Red Cross Note,” at « 36th/856th BSs Norton Crew, » The Wartime Experiences of the Carpetbaggers, accessed April 28, 2021, http://www.801492.org/Air%20Crew/Norton/gillikin-RedCross-Ltr.jpg .

29 “Nuit de 14 au 15 Aout;” “French Erect Monument to Tampa Flier;” “Undated letter to Serge Blandin,” at « 36th/856th BSs Norton Crew, » The Wartime Experiences of the Carpetbaggers, accessed April 28, 2021, http://www.801492.org/Air%20Crew/Norton/1992-03-p04-Gillikins%20Story.jpg.

30 “Undated letter to Serge Blandin,” at « 36th/856th BSs Norton Crew, » The Wartime Experiences of the Carpetbaggers, accessed April 28, 2021, http://www.801492.org/Air%20Crew/Norton/1992-03-p04-Gillikins%20Story.jpg; Fish, They Flew at Night, 221.

31 “French Erect Monument To Tampa Flier.”

32 Ibid.

33 “Rhone American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed July 29, 2021, https://www.abmc.gov/Rhone.

34 “U.S., Headstone and Internment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for Connie O. Walker Jr., service number 0821120.

35 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2021), entry for Thomasine L. Walker and Aaron D. Blankenship, film number 001903286; “Aaron D. Blankenship,” Find a Grave, accessed April 28, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/113537307/aaron-d.-blankenship.

36 “Blankensip, Thomasine L.,” The Tampa Tribune (Tampa, Florida), July 2, 2004, Ancestry.com.

37 Fish, They Flew at Night, 221 – 222.

38 “Le 70e anniversaire du crash de l’avion américain commémoré,” Le Pays (Duerne, France), September 11, 2014, accessed July 30, 2021, https://www.le-pays.fr/duerne-69850/actualites/le-70e-anniversaire-du-crash-de-lavion-americain-commemore_11139532/.

39 Ibid.