S Sgt George Toney Jr. (March 11, 1909 – October 17, 1943)

306th Bombardment Group, Eighth Air Force

By Haley Shaner and Brett Nystrom

Early Life

George Toney Jr. was born on March 11, 1909 to Syrian immigrants from the Ottoman Empire.1 From the 1890s to 1914, displaced Muslim populations from around the region migrated into the Ottoman Empire. Significant in-migration and a weak central government, coupled with European imperialism, war, and economic stagnation, created trying conditions that inspired many, called Assyrians at the time, to emigrate to industrialized nations like the US.2

A part of this wave of migration, the Toney family lived in Jacksonville alongside many Syrian immigrant families, forming a close-knit community with a shared culture.3 Toney Jr.’s father, George Toney Sr., owned a produce wholesaler business in Jacksonville, FL. His mother, Ada Toney, cared for George Toney Jr. and his six siblings. Toney Jr. had an older sister, Mary (1907), and five younger siblings, Sarah (1911), Nellie (1912), Helen (1914), Edward (1916), and Charles (1922).4

During the 1920s, all the Toney children attended school, but only Helen completed all four high school years.5 Toney Jr. left high school, having completed only one year, likely to help his father in the family produce shop. Despite the financial hardships of the Great Depression, Toney Jr. married his love, Ms. Eleanor Rose, in 1930, a short time after he turned twenty-one. In 1934, George and Eleanor welcomed their daughter, Patsy Toney.6 By the mid-thirties, Toney Jr.’s mother, Ada, passed away, and by 1938, Toney Jr. and Eleanor divorced.7

Military Service

Toney Jr. registered for the draft on October 25, 1940, followed by his brother, Edward, one day later.8 Soon after signing up for the draft, Toney Jr. found love again with Ms. Sophie Antone. The two wed on March 25, 1941, in Macclenny, FL. One year later, Toney Jr. enlisted at Camp Blanding in Starke, FL, on August 19, 1942, at the age of thirty-three.9

After basic training at Camp Blanding, Pvt. George Toney likely joined the 306th Bombardment Group, Eighth Air Force. He headed west for bombardier training at Gowen Field, ID (in what is today the Boise Airport) and, later, more training in Wendover Field, UT, after the unit relocated. Activated for combat on March 1, 1942, at Gowen Field, the 306th Bombardment Group consisted of airmen from around the country. It eventually relocated to Thurleigh, England, at the beginning of September 1942.10

Along with the rest of the 306th Bombardment Group, Toney Jr. received further training at the airbase in Thurleigh. The infrastructure within the airbase could not efficiently house the ever-growing number of American airmen arriving from overseas. Toney Jr., like much of the 306th, had to sleep in tents and follow an irregular schedule, including taking rotating shifts over a 24-hour period to ensure the base’s facilities operated efficiently until the airbase could accommodate the force. The 306th Bombardment Group trained alongside British crews, learning British codes, phrases, and techniques to better work alongside them in the air. Airmen practiced these techniques through the bombing of dummy targets placed along the English countryside.11

While training and preparing for the war in continental Europe, Toney Jr., and other Floridians spoke with war correspondent, Marjorie Avery. A photo of their conversation appeared in this Miami Herald article,

which referred to their location as “Somewhere in England” to avoid divulging information regarding the whereabouts of Allied servicemen and operations to the Germans. The Herald likely captured the photo in Thurleigh, but it may have also taken it in Duxford, a significant hub for servicemen in the Eighth Air Force and the present-day location of the American Air Museum in Britain.12 On September 28, 1942, the US Army Air Forces declared the 306th ready for combat, joining the rest of the Eighth Air Force.13

The Eighth Air Force intended to deprive Germany of its ability to wage war by destroying ammunition and aircraft assembly plants – infrastructure vital to the German war industry.14 Between their activation in 1942 and the beginning of 1943, most 306th Bombardment Group missions flew daylight aerial strikes within B-17 Flying Fortress aircraft formations. More dangerous than night attacks, the bombers reached their targets more accurately. During this time, the 306th flew thirty-five missions, molding them into an experienced, battle-hardened force.15 The 306th targeted various industrial targets throughout the war, including the bombing of railroad infrastructure in both Rouen and Lille, France, and wartime industries from Hannover to Stuttgart, Germany. In addition to their task of targeting wartime industry, the 306th also conducted raids on German naval operations, such as the bombing of submarines at Bordeaux, France, and the disruption of shipbuilding in Vegesack, Germany.16 Toney Jr., as a bombardier, operated at the nose of the plane, shooting at enemy aircraft while loading and fusing bombs to strike targets on the ground. The crew’s survival and the mission’s success relied heavily on Toney’s position within the plane. Toney Jr. also actively communicated with the pilot to ensure successful bomb delivery.17

On October 17, 1943, the Eighth Air Force participated in the Second Schweinfurt Raid, also known as “Black Thursday.”18 US Allied command tasked the Eighth Air Force with a mission to destroy German factories producing ball bearings, an essential ingredient in enemy aircraft production. Schweinfurt’s factories turned out two-thirds of all ball bearings produced in Germany, and destroying that production would cripple the German war effort in the air.19 This mission was the first time George Toney Jr. flew in the B-17 Flying Fortress, nicknamed the Jackie Ellen.20 The crew joining Toney Jr. hailed from across the US, including pilot Douglas White (TX), co-pilot Emil Rasmussen Jr. (OR), navigator Carl Alexander (NY), waist gunner Charles Adams (PA), waist gunner William Earnest (PA), ball turret gunner Francis Pulliam (CA), top turret gunner/flight engineer Gus Riecke (OR), radio operator Joseph Bocelli (PA), and tail gunner Walter Sherrill (CA).21

The US Army Air Forces considered the mission a strategic success; however, they also recognized the disastrous loss of life for the crews of aircraft involved. Of the eighteen 306th Bombardment Group aircraft on the mission, only eight planes returned to Allied territory.22

The Jackie Ellen suffered severe damage to its horizontal stabilizer from German aircraft, according to Captain Charles T. Scholfield, who saw the Jackie Ellen from his own aircraft nearby.23 The Jackie Ellen exploded mid-air shortly after the initial hit, breaking in half at the radio room.

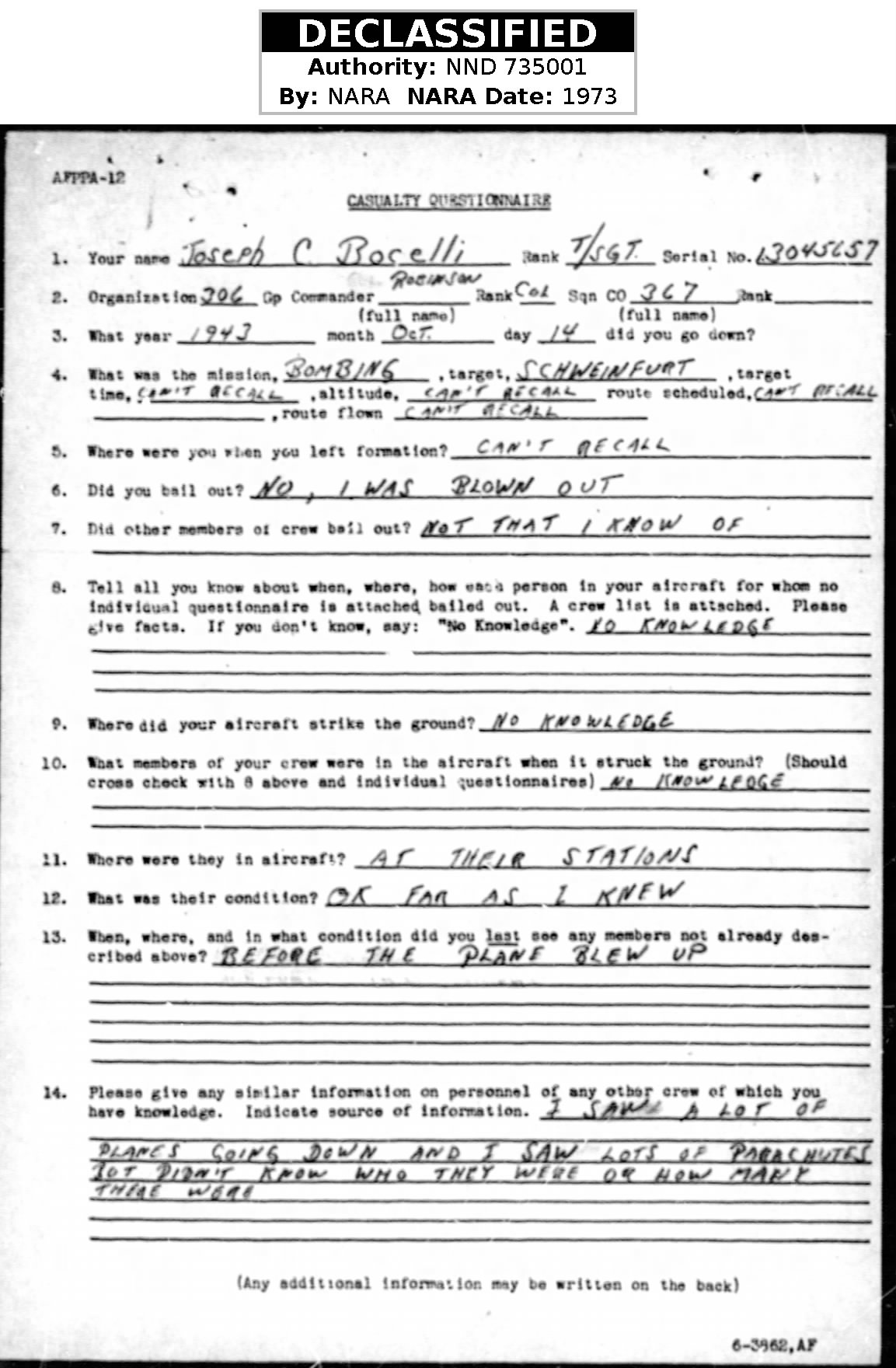

The plane’s remains fell over Northwest Thuringia, Germany, forty minutes before reaching their target in Schweinfurt, Bavaria, Germany. George Toney Jr. and eight of his crewmates perished. Joseph Bocelli, the lone survivor, spent the remainder of the war as a prisoner of war (POW), eventually returning home to Philadelphia, PA, after the war’s end.24 After his liberation, Bocelli completed a casualty questionnaire, a key element of any Missing Aircrew Report. On the page, reproduced here, Bocelli, asked if he bailed out, responded, “No, I was blown out,” shining light on the final moments of the lives of Toney Jr. and the rest of the crew of the Jackie Ellen.25 Once blown clear of the aircraft, Bocelli managed to open his parachute and landed not far from their target in Schweinfurt, Germany.26

Legacy

After the Second Schweinfurt Raid, the 306th Bombardment Group continued to serve in significant operations within the European Theatre, destroying enemy infrastructure related to the German war effort. Starting in February 1944, the 306th bombed V-Weapons sites, home to the infamous V-2 missiles, which terrified Allied forces and destroyed European cities.27 After the war, the 306th Bombardment Group and the 305th Bombardment Group worked on the then-classified Casey Jones Project to capture US Army post-war reconnaissance photos of Iceland, Europe, and Africa using the Eighth Air Force’s vast B-17 Flying Fortress fleet. Officially deactivated from service on July 1, 1947, the men of the 306th became the longest-serving group in the Eighth Air Force. A museum and memorial dedicated to the 306th Bombardment Group currently resides on its former airbase in Thurleigh, England.28

George Toney Jr. left behind his daughter, Patsy, his wife, Sophie Toney, his father, George Toney Sr., and his siblings. In 2017, Patsy left virtual flowers for her father on the website Find A Grave, with a note wishing to see him soon and reminding us how much she missed the father she lost when she was nine years old. Sophie did not remarry and passed away on March 25, 2005.29 The US military awarded Staff Sgt. George Toney Jr. an Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters for completing at least fifteen bombing missions and posthumously awarded him the Purple Heart.30 He is interred at the Lorraine American Cemetery at Saint-Avold, France, Plot A, Row 26, Grave 51, where he may forever rest in peace.31

1 George Toney, Find a Grave, accessed September 17, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56661660/george-toney.

2 Kemal H. Karpat, “The Ottoman Emigration to America, 1860-1914,” introduction, in Studies on Ottoman Social and Political History: Selected Articles and Essays (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2002), 90–131.

3Kathleen Cohen, “Immigrant Jacksonville: A Profile of Immigrant Groups in Jacksonville, Florida, 1890-1920,” master’s thesis, (University of North Florida, 1986), 47-60.

4 “1930 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com. (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed September 17, 2022), entry for George Toney Jr., Jacksonville, Duval County, Florida.

5 “1930 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com. (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed September 17, 2022), entry for Helen Toney, Jacksonville, Duval County, Florida.

6 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry.com. (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed September 17, 2022), entry for George Toney Jr., Eleanor Rose Toney, and Patsy Toney, Jacksonville, Duval County, Florida.

7 “Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, Ancestry.com. (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed September 17, 2022), entry for Ada Toney, Jacksonville, Duval County, Florida; “Florida, U.S., Divorce Index, 1927-2001,” database, Ancestry.com. (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed September 17, 2022), entry for George Toney Jr., Jacksonville, Duval County, Florida.

8 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry.com. (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed September 17, 2022), entry for George Toney Jr., serial number 34247980, and entry for Edwin Toney.

9 Florida Marriages, 1830-1993,” database, FamilySearch.com. (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:234K-346: accessed September 17, 2022), entry for George Toney; “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” entry for George Toney Jr.

10 Charles Westgate, “The Reich Wreckers: An Analysis of the 306th Bomb Group during World War II,” (Masters Thesis, Air University, 1998), 6, 72.

11 Charles Westgate, “The Reich Wreckers,” 11.

12 “Herald War Correspondent Marjorie Avery,” The Miami Herald (Miami, FL), Sep. 26, 1943; “About IWM Duxford,” Imperial War Museums, accessed June 26, 2023, https://www.iwm.org.uk/iwm-duxford/about.

13 Westgate, “The Reich Wreckers,” 11; “42-37720 Jackie Ellen,” American Air Museum in Britain, accessed September 18, 2022, https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/aircraft/42-37720.

14 Westgate, “The Reich Wreckers,” 14.

15 Westgate, “The Reich Wreckers,” 16.

16 “306th Bomb Group The Reich Wreckers,” American Air Museum in Britain, accessed March 5, 2023, https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/unit/306th-bomb-group-reich-wreckers.

17 AAF, “The Bombardier,” in Pilot Training Manual for the Flying Fortress B-17 (AAF Office of Assistant Chief of Air Staff, 1945), pp. 18-22.

18 John M Curatola, “‘Black Thursday’ October 14, 1943: The Second Schweinfurt Bombing Raid,” The National WWII Museum: New Orleans, published October 16, 2022, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/black-thursday-october-14-1943-second-schweinfurt-bombing-raid.

19 John T. Correll, “The Cost of Schweinfurt,” Air & Space Forces Magazine, published February 1, 2010, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/0210schweinfurt/#:~:text=World%20War%20II%20created%20a,ball%20bearings%20and%20roller%20bearings.

20 “42-37720 Jackie Ellen,” American Air Museum in Britain; “Missing Air Crews Reports,” database, Fold3.com (www.fold3.com: accessed March 28, 2023), entry for aircraft 42-37720.

21 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” entry for Douglas H. White, Serial number 18063911; entry for Emil O. Rasmussen Jr., Serial number 19047718; entry for Carl A. Alexander, Serial number 12051889; entry for Charles A. Adams, Serial number 13113209; entry for William R. Earnest, Serial number 13041315; entry for Francis W. Pulliam, Serial number 39393944; entry for Gus Riecke, Service number 39092509; entry for Joseph C. Bocelli, Service number 13045657; entry for Walter D. Sherrill, Serial number 39529633; “42-37720 Jackie Ellen,” American Air Museum in Britain.

22 Westgate, “The Reich Wreckers,” 23.

23 “Missing Air Crews Reports,” database, Fold3.com (www.fold3.com: accessed March 28, 2023), entry for aircraft 42-37720.

24 “Pennsylvania, U.S., Veteran Compensation Application Files, WWII, 1950-1966,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed September 17, 2022), entry for Joseph Bocelli. Bocelli had two kids, Augustine (1949) and Dolores (1958), passing away on February 19, 1993, at the age of 72; “Joseph C. Bocelli,” Find a Grave, accessed February 1, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/110906986/joseph-c-bocelli.

25 “Missing Air Crews Reports,”entry for aircraft 42-37720.

26 “42-37720 Jackie Ellen,” American Air Museum in Britain; Dave Osborne, “B-17 Fortress Masterlog,” 91st Bombardment Group, accessed May 31, 2023, https://www.91stbombardmentgroup.com/Aircraft%20ID/FORTLOG.pdf.

27 Westgate, “The Reich Wreckers,” 26.

28 Robert J. Boyd, Project ‘Casey Jones’: Post-Hostilities Aerial Mapping; Iceland, Europe, and North Africa, June 1945 to December 1946 (Offutt Air Force Base: Strategic Air Command, 1988); Westgate, “The Reich Wreckers,” 73; “The 306th Bombardment Group Museum,” 306th Bombardment Group Museum, accessed March 8, 2023, https://www.306bg.co.uk/.

29George Toney, Find a Grave, accessed September 17, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56661660/george-toney.

30 “U.S., Headstone and Interment Records for U.S., Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942-1949,” database, Ancestry.com. (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed September 17, 2022), entry for George Toney Jr. Serial number 34247980.

31 George Toney, Find a Grave. “George Toney Jr.,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed June 30, 2023, https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/toney%3Dgeorge.