Charles Stripling (1927 – June 12, 1945)

Steward’s Mate Second Class USNR

by Levi Berry and Michael Richardson

Early Life

Charles (Charlie) Stripling was born in early 1927 in Beards Creek, GA, to Willie and Isam Stripling.1 Both his mother, Willie (1895), and his father, Isam (1900), grew up in Georgia.2 Isam came from Odum, GA, where he lived with his parents, Janie and Abraham Stripling, both born in the mid-1880s. The census takers described Abraham as black, but Janie and their children as “mulatto,” a status classified as “tragic” in Jim Crow America.3 Despite the family’s adversity, they prioritized the education of their five children and a niece, Blanche, who lived with them. According to the 1920 census, all attended school.4

Willie and Isam married in about 1925, staying in Beards Creek, GA where they had Charles, followed by three daughters, Jernita (1929), Dorothy (1933), and Irene (1937). Isam supported the family by working on “general farms,” likely as a sharecropper.5 Georgia agriculture was predicated mainly on producing “King Cotton” at the turn of the century. In 1915, however, a pest known as the boll weevil spread into Georgia and began destroying most of the cotton crop throughout the state. Combined with outdated farming practices, it resulted in topsoil erosion by the 1920s. Georgia’s production of almost 3,000,000 cotton bales in 1911 dropped to roughly 500,000 by 1923. The state never recovered to what it once was, producing just under two million bales in 2018.6

Despite the likely increased hardships, the family did not move to Florida until the height of the Great Depression in the 1930s, presumably to improve their economic conditions and provide their children with a better life. Willie and Isam participated in a lesser-known part of the Great Migration, moving south instead of north. The Great Migration, with the significant internal migration of Black Americans from the 1910s until the 1970s, included approximately six million people who moved from the American South to other parts of the country to “escape racial violence, pursue economic and educational opportunities, and obtain freedom from the oppression of Jim Crow.”7 The Stripling family settled in Fort Lauderdale, where they had their youngest child, Irene, born on 25 April 1937.8

The Stripling family lived at 608 NW 6th Street in Lincoln Park, Fort Lauderdale, FL. They paid six dollars a month in rent: about $130 in 2023 dollars.9 Fort Lauderdale, created as a fort during the Second Seminole War in 1838, became an incorporated city on March 27, 1911.10 By 1944, Fort Lauderdale advertised itself as “conservative and a ‘class’ community,” and a likeness to “the most fragile Venetian Island city,” with a population of 41,000. The city served as a training ground for servicemen, military industry, and the “greatest yacht highway” in the world (during winter when the wealthy northerners visited to escape the cold).11

The African American residents of Lincoln Park, where the Striplings lived, made only a fraction of the average salary of whites in the area.12 They also lived in inexpensive housing along the park, likely a result of the recently developed practice of redlining, which allowed banks to perpetuate residential segregation even when New Deal policies may have allowed African Americans to receive federal aid, including mortgages, on the same footing as white citizens.13 Nevertheless, the family believed in the opportunities associated with education. Charles attended Dillard High School, Fort Lauderdale’s first African American school. Opening in 1907 and named initially Colored School Number Eleven, Dillard High School sought to break the mentality that African American students would only have a career in agriculture.14

In 1936, the police arrested Isam and two other African Americans for a series of robberies in “the colored section” of town. While we do not know if he was ever charged or convicted of these crimes, or what may have motivated him if he did break the law. We do know his family faced challenging conditions during the financial crisis of the Depression and the deep-seated, institutional racism, including police brutality.15 Despite the arrest, Isam sought other opportunities to help his family, learning to be an automobile mechanic at Halls Auto Parts, where, by 1940, he earned an annual salary of $332 working eighty-four hours a week (well under the average yearly income in 1940 of $1,368).16 The family continued to stay close to their family in Georgia, as Isam indicated his father, Abraham, as a trusted contact on his draft registration card.17

Military Service

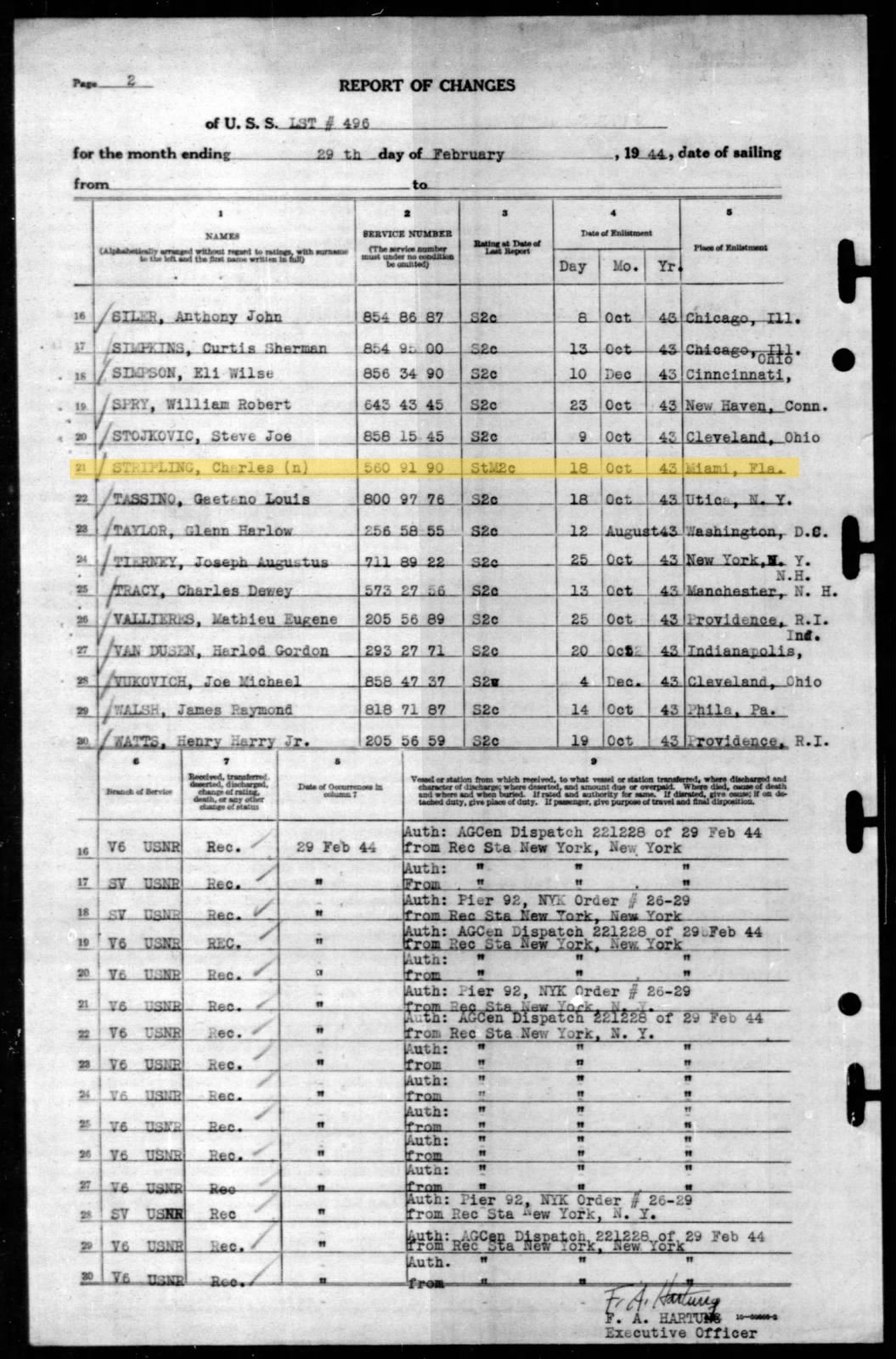

Charles entered the United States Naval Reserves at sixteen years old on October 18, 1943, in Miami.18 During World War II, the military allowed people to enter at the age of sixteen with parental consent, so Charles likely did not need to lie to join the service.19 While in the USNR, Charles achieved the rating and rank of Steward’s Mate Second Class Petty Officer (STM2). A Steward’s Mate rating was nearly exclusive to African Americans and Filipinos and was the only job available to them on combat vessels. The primary job of a Steward’s Mate is serving food in the officers’ wardroom, cleaning and organizing officers’ living quarters, and assisting cooks in the galley, although they also trained as gunners in the event of a wartime emergency.20 Despite Congress officially banning discrimination with Executive Order 8802: Prohibition of Discrimination in the Defense Industry (1941), segregation remained firmly in place.[21]

The Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, adamantly opposed black men in combat roles and said that the Navy would “remain lily-white.”22 African American recruits faced racial slurs and violence from white soldiers and sailors despite every service member fighting for the same cause. According to one black Navy Veteran, white Recruit Division Commanders at boot camp during the 1940s told him, “there were ‘only two kinds of n****s – a good n**** and a dead n****.’”23 The Navy even hesitated to award African Americans war medals.24 Senators also believed African Americans were cowardly and avoided fighting.25 Despite all his obstacles, Charles still found the motivation to serve his nation in the Navy.

Charles was assigned to a Landing Ship Tank, known as an LST.26 He sailed on the USS LST-496, stationed at Pier 92 in New York City on February 29, 1944. Charles was one of fifteen sailors serving as the USS LST-496 ship’s company. These sailors were responsible for routine shipboard operations while on deployment and maintenance when in port. Pictured here is the February 1944 Muster Roll taken aboard the USS LST-496 featuring Stripling.27 LSTs served as the work horses of amphibious landings carrying troops and land vehicles, capable of transporting roughly 2,100 tons of material and approximately 200 soldiers.28 In 1938, American and British manufacturers developed and tested LSTs as vessels designed to land tanks onshore. These ships created anxiety for many military officials, so much so that many sailors joked that their initials stood for “Large Slow Target.”29 Missouri Valley Bridge & Iron Company built the USS LST-496 in Evansville, IN, on August 24, 1943.30 The ship sailed down the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico en route to Pier 92, New York City.31

Shortly after Charles arrived, the 496 left New York for Providence, RI, to take on its load of steel pontoons and smaller ships.32 The ship’s last North American stop was in Halifax, Nova Scotia, to join the convoy en route to Southampton, England.33 The 496 saw its first attack only one hour after departing from Halifax. As the convoy lost a food supply ship in the attack, the crew of the 496 and others in the group had to travel the Atlantic Ocean on a diet of Spam.34

To prepare for the incoming American forces, the British government had all citizens of South Hams around the Slapton Sands, a beach within Lyme Bay on the Bristol Channel in southern England, removed from their homes. Locals did not appreciate their government ordering them to leave their homes for several reasons, including fears about losing the region’s cultural heritage. Local protest did not sway the Allied leadership as the coastline resembled the beaches in Normandy where the Allies planned to land, and the Allies wanted their training to remain top secret.35 The beach presented an ideal training scenario for the imminent operation for storming Normandy: “I thought we were off the coast of France,” said Joseph R. Sandor, a USN Petty Officer at the time.36

On April 26, 1944, the 496 participated in its first mission, a series of exercises known as Exercise Tiger. A disastrous event, Edward Filo, a News Staff writer for The Stuart Daily News, refers to as “one of the best-kept secrets of World War II and U.S. military history.”37 Exercise Tiger was intended to prepare the ships and personnel38 for landing at designated beaches in Normandy as part of preparations for the massive amphibious assault. Military leaders planned to simulate the attack in and around Lyme Bay along the southern coast of England.39 Under the high stakes and dangerous circumstances that Exercise Tiger provided, the US and Royal navies “insisted on radio silence during Exercise Tiger, except in cases of imminent danger,” which would likely be too late for action.40

As Exercise Tiger’s preparations ended, German ships and radar caught wind of the exercise. The German Luftwaffe sent planes over Lyme Bay for reconnaissance and saw much of the military stockpile that lay along the English coast.41 Despite Allied personnel witnessing the horror on enemy vessels, they had no preparations for what came next. As Exercise Tiger commenced after 0130 in the morning, personnel caught sight of the green tracers that went with the bullets on German E-boats.42 The radio silence made for a disastrous event, with ships firing in response to the Germans, engendering friendly fire. While the Germans immediately left the area, mass confusion reigned on the Allies’ side. The fully refueled vehicles onboard the damaged transports caused “the most spectacular fireworks.” Army personnel onboard had not received training on abandoning flaming ships. Some service members were still wearing full packs when jumping overboard. Heavy steel helmets and improperly fastened lifebelts also hastened drowning.43

The 496 participated in the catastrophe when a German E-boat drove between the 496 and the USS LST-511. A German E-boat, was “without a doubt the most sinister, purpose-built killing machines,” USN vessels moved at 12 or 13 knots; In comparison, the E-boat moved at 40 knots,44 In the dark of night, the LSTs tried shooting back at the German target after the E-boat left, resulting in a friendly fire incident exacerbated by the communication blackout.45 Joseph R Sandor, a torpedo survivor, shares his experience with a British news report published more than forty years later:

In the aftermath of the training gone array, some tired personnel thought they saw masses of dark seaweed bobbing on the waves in the predawn darkness. When the sun came up, clearing away the mist…(the) horrified (sailors) saw the dark shapes, hundreds of them, were actually the bodies of fellow American soldiers and sailors floating in the English Channel.46

The Germans sank or damaged multiple LSTs, and “you could actually see the boats turn into molten metal.”[47] Most troops experienced their first combat night during a training exercise, a frightening prelude to the war. Over 1,000 men died in the Allies’ secret staging for the invasion operations, giving military leaders pause, with some arguing that the Allies should scrap the invasion.48 Despite the disaster, Allied leaders decided to carry on with the massive amphibious landings in Normandy.49

Exercise Tiger had been forgotten for thirty years, until 1974 when a fisherman, Ken Small, found an undamaged Sherman tank of the 70th Battalion sunk sixty yards off the beachline on the seafloor in Lyme Bay.50 In the immediate aftermath, the US military leadership kept the disaster a secret to preserve personnel morale. Although not kept secret after the war, official histories made little mention of the catastrophe. Following Small’s discovery and attention from survivors following the fiftieth anniversary, the site’s memorial, which includes the recovered Sherman tank, now sits on the plinth in Devon, England. It serves as a steadfast reminder of the sacrifices of brave men in uniform who participated in Operation Tiger.51

Though damaged, the 496, seen below during preparations for the landings, joined the fight on D-Day as part of the Battle for Normandy. Steward’s Mate Charles Stripling and the rest of his crew shuttled men and material across the channel to Omaha Beach beginning on June 6, 1944.52 The men of the 496 braved treacherous waters, the looming threat of German E-boats, and the strafing from Luftwaffe planes above. And, despite efforts to remove sea mines, they faced invisible dangers underwater. After unloading the men and material they carried, Stripling and the crew of the 496 returned to England to resupply and return to the battle.53

Five days later, the 496 returned to France again to bring more men and material on June 11, 1944. This time, it struck a sea mine, killing Charles Stripling and most of the ship’s crew.54 Pictured here are photos of the 496 during wartime preparations and after its sinking.55 Aboard the nearby USS LST-502, Leon Schafer remembered the LSTs returning to England and making their second trip to Omaha Beach. Schafer recalled watching the explosion of the 496:

It was a pretty day. We approached close to the beach, I happened to be out on the wings of the ship. I was not on duty yet, I think I was just wanting to see what was going on, and the LST-496 was to our starboard and it was also going in, and it hit a sea mine, a 750-pound sea mine. Now those particular sea mines were set after so many ticks of the ships that went over it, that it would explode on the next one. And the explosion, I saw daylight under this LST, the way it detonated. The detonation was so great, I didn’t believe what I was looking at. She was loaded with tanks that had already been unshackled, prepared to hit the beach, and Army personnel, and immediately we stopped and sent our small boats over to see what they could do. Canadian Corvettes pulled up along the sides and tied lines to her to keep her from capsizing and we brought casualties over. The way the detonation was so great, some people were thrown up against the overhead and some of our men came back and said they stuck to the ceiling…It was one of our stories never told, the ship, the 496, until many years later.56

The sea mine hit towards the ship’s front end, near the officer’s quarters, where Steward’s Mates like Charles worked. The War Department declared Stripling missing after the 496 sank but waited to declare him deceased, following protocol, until one year and one day later, on June 12, 1945.57

Legacy

The LSTs played a critical role in the success of D-Day and in the logistical support that Normandy provided to the Allied troops in France and Germany. Soldiers and sailors like Charles Stripling brought inspiration to Allied forces all over the globe as they took part in the largest seaborne invasion in human history.58 Petty Officer Charles Stripling and the 496 provided the necessary support to capture Omaha Beach.59 Charles Stripling’s name appeared in the Fort Lauderdale News on August 31, 1944, indicating he was among the local men serving in the armed forces who had been reported as missing. We know that the Stripling family believed their son was alive but missing for many months after his death, as they included him as serving in the Navy on the 1945 Florida census.60

Like Charles, his siblings attended Dillard High School, even though Charles never had the opportunity to finish his education.61 His sister, Jernita, went on to work as a runner for a mechanic, likely working with her father.62 At some point after the war, Charles’ father, Isam Stripling, may have been moved by the loss of his son to seek solace in his faith. Isam became a reverend at St. Phillips CME Church in Fort Myers, FL.63 Charles’ parents, Willie and Isam, spent their later years in Fort Myers, passing away in 1993 and 1990, respectively.64

The 496 received one battle star for its service on D-Day.65 An extraordinary feat for anyone, Charles Stripling earned and was posthumously awarded a Purple Heart.66 The Navy never recovered Steward’s Mate Second Class Charles Stripling’s body. He is memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer, France.67 Although the Allied Forces sacrificed many lives and resources, the D-Day operations in Normandy were successful, leading to the liberation of France. Without Charles and others like him, the overall Allied victory and the war’s conclusion would not have been possible.

1 “1930 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Charles Stripling, Beards Creek, Georgia. In some documents, Charles has the nickname “Charlie,” and in some cases Isam is spelled as “Isson” or other misspellings. The latter seems to be an error as most other records spell his name as “Isam,” including documents he wrote on himself. We are using the spelling he used. The Federal Census record includes an estimated date of birth. Given Charles’ age of three and a half on the 1930 census, taken in April, we estimate that Charles was born in January 1927. Various reasons may exist for these inconsistencies such as home births and federal disenfranchisement of poor families in rural Southern States.

2 “1930 U.S. Census,” entry for Charles Stripling; We found no record containing Willie’s exact birthday, based on census records we estimate between 1895-1898; “U.S. WWII Draft Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Isam Stripling, 1451.

3 “1910 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Isam Stripling, Odum district, Georgia; “The Tragic Mulatto Myth,” Jim Crow Museum, accessed November 14, 2023, https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/mulatto/homepage.htm.

4 “1920 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Charles Stripling.

5 “1930 U.S. Census,” entry for Charles.

6 William P. Flatt, “Agriculture in Georgia,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, accessed December 5, 2023, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/business-economy/agriculture-in-georgia-overview/.

7 “African American Heritage,” National Archives, accessed December 5, 2023, https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/migrations/great-migration.

8 “Irene Benson Grave,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/18067977/irene_s-benson; “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Willie and Isam Stripling, Lincoln Park, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

9 “Fort Lauderdale City Directory, June 1944,” database, Ancestry.com (ancestry.com: accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Charles Stripling, 412; “How Much is $1 in 1940 Worth Today? Inflation Calculator,” Carbon Collective, accessed November 14, 2023, https://tools.carboncollective.co/inflation/us/1940/1/. ; “1940 U.S. Census,” entry for “Willie and Isam.”

10 “About Fort Lauderdale,” City of Fort Lauderdale Florida, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.fortlauderdale.gov/government/about-fort-lauderdale#:~:text=Incorporated%20on%20March%2027%2C%201911ten%20largest%20cities%20in%20Florida; “The Seminole Wars,” Seminole Nation Museum, accessed November 14, 2023, https://seminolenationmuseum.org/history-seminole-nation-the-seminole-wars/.

11 “Fort Lauderdale City Directory, June 1944,” entry for Charles Stripling, 10, 12.

12 “Redline: Historical Bus Tour, Legacy Unveiled: Journey Through Miami’s Hidden History, 2025,” accessed April 30, 2025, https://southfloridapoc.org/redlining/#:~:text=Redlining%2C%20a%20discriminatory%20practice%20dating,communities%20of%20Miami%20and%20Broward.

13 “MapMaker: Redlining in the United States,” National Geographic, accessed November 14, 2023, https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/mapmaker-redlining-united-states/.

14 “Stripling Missing,” The Fort Lauderdale (Florida) Daily News, August 31, 1944, 2; “Youths Entertained,” Fort Lauderdale Daily News, June 1950, 16. On the history of Stripling’s school, see Destinee A. Hughes, “A Historic Look at Dillard High School,” Venice Magazine – Fort Lauderdale’s Magazine, last modified September 6, 2015, https://venicemagftl.com/in-retrospect-lucky-number-eleven/ and “Old Dillard Museum,” Broward County Public Schools, accessed November 14, 202, https://www.browardschools.com/Page/35769. For more details about the African American educational network established in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries see the interactive map featuring 259 schools founded for education of African Americans, Michael Richardson, Mapping Reconstruction, accessed May 22, 2025, https://arcg.is/1P0DWW.

15 “3 Negroes Held For House Thefts,” Fort Lauderdale News, June 22, 1936, 2. https://www.newspapers.com/image/230164444.

16 “WWII Draft Registration Card,”entry for Isam Stripling; “1940 U.S. Census,” database, , entry for Willie and Isam Stripling,; Diane Petro, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? The 1940 Census: Employment and Income,” National Archives, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2012/spring/1940.html#:~:text=The%2016th%20decennial%20census%20of,5.2%20percent%20in%20the%201920s .

17 “WWII Draft Registration Card,” entry for Isam Stripling.

18 “USN Muster Roll,” database, fold3.com (accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Charles Stripling. 44 February, 1944.

19 Gilbert King, “The Boy Who Became a World War II Veteran at 13 Years Old,” Smithsonian Magazine, accessed November 14, 2023. .https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-boy-who-became-a-world-war-ii-veteran-at-13-years-old-168104583.

20 Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum. “Steward’s Scrapbook: Photographs of Thomas Edwin Murray.” Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum. Accessed May 22, 2025. https://www.patriotspoint.org/artifacts-archives/stewards-scrapbook-photographs-thomas-edwin-murray.

21 “Executive Order 8802: Prohibition of Discrimination in the Defense Industry (1941),” National Archives, last modified February 8, 2022, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/executive-order-8802.

22 Joseph Conklin LaNier II, “My War on Two Fronts,” American Legion, accessed December 5, 2023, https://www.legion.org/magazine/94871/my-war-two-fronts; President Harry S. Truman, Executive Order 9981: Desegregation of the Armed Forces, July 26, 1948, National Archives (.gov). Segregation in the armed forces continued until after the war, when on July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981: Ending Segregation in the Armed Forces.

23 LaNier, “Joseph LaNier Interview,”; the offensive language in this sentence is an exact quote from someone who had been a victim to it; Recruit Division Commanders are the navy equivalent to the army’s Drill Sergeants; for more information on Recruit Division Commanders, visit https://www.bootcamp.navy.mil/Subs-and-Squadrons/#:~:text=RDCs%20are%20Chief%20Petty%20Officers,endeavor%20to%20be%20taken%20lightly.

24 Wills, “Remembering Doris Miller.”

25 “African American Press, December 1944,” database, ProQuest History Vault (hv.proquest.com accessed November 14, 2023), 264, https://www.proquest.com/archival-materials/african-american-press-december-1944/docview/2903842563/se-2?accountid=10003.

26 “US LST Association,” https://uslst.org.

27 Charles Stripling on February 1944 Muster Roll. https://www.fold3.com/sub-image/281765197/stripling-charles-us-world-war-ii-navy-muster-rolls-1938-1949.

28 Paula Ussery, June 16, 2008, “LST in WWII,” www.army.mil/Army Heritage Museum, last modified June 16, 2008, https://www.army.mil/article/10067/lst_in_wwii#:~:text=The%20LST%20was%20specifically%20designed,tons%20and%20approximately%20200%20soldiers.

29 Nigel Lewis, Channel Firing, (Penguin Group, 1989), 32; Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Vol. IV (United States Navy, 1969), 667; Lewis, Channel Firing, 24.

30 “LST-496,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/l/lst-496.html.

31 “Heinz History Center: Dravo Leads the “Cornfield Navy”

32 Lewis, Channel Firing, 30.

33 “USS LST-496,” NavSource Online: Amphibious Photo Archive, accessed on November 14, 2023, https://www.navsource.org/archives/10/16/160496.htm; “Frank Derby Story – LST 496,” Exercise Tiger Memorial, accessed November 14, 2023, https://exercisetigermemorial.co.uk/frank-derby-story-lst-496#:~:text=LST%20496%20sank%20in%2018,the%20rest%20of%20the%20war.

34 Lewis, Channel Firing, 41.

35 Lewis, Channel Firing, 9-41.

36 Edward Filo, “Operation Tiger Remembered,” The Stuart News, December 7, 1987, A3. https://www.newspapers.com/image/885881507/.

37 Filo, “Operation Tiger Remembered,” A1.

38 “D-Day Landing Designations,” https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1944/overlord/operation-neptune.html. Each D-Day beach landing site is designated with Particular naming conventions such as “Utah Beach,” or “Omaha Beach.”Designations such as “Force O” stood for “Omaha Beach” directing crews of the various LSTs on where to land troops or materials.

39 “Exercise Tiger: Disaster at Slapton Sands, 28 April 1944,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1944/exercise-tiger.html.

40 “Exercise Tiger: Disaster at Slapton Sands, 28 April 1944.”

41 “Exercise Tiger: Disaster at Slapton Sands, 28 April 1944,” Additional reconnaissance over the English Channel was ordered under Hitler’s Directive No. 5.

42 “Exercise Tiger: Disaster at Slapton Sands, 28 April 1944.”

43 “Exercise Tiger: Disaster at Slapton Sands, 28 April 1944.”

44 “Last of its kind, deadly Nazi E-boat rises again: Seized by the British,” https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna30977019.

45 “USS LST-496,” NavSource Online: Amphibious Photo Archive, photos, accessed on November 14, 2023, https://www.navsource.org/archives/10/16/160496.htm; Edward Filo, “Operation Tiger Remembered,” The Stuart News, December 7, 1987.

46 Filo, “Operation Tiger Remembered,” A3.

47 Filo, “Operation Tiger Remembered,” A3.

48 Filo, “Operation Tiger Remembered” A3.add the page.

49 “Exercise Tiger: Disaster at Slapton Sands, 28 April 1944.”

50 “Exercise Tiger Memorial,” Atlas Obscura, accessed November 16, 2023, https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/exercise-tiger-memorial.

51 “Excercise Tiger Blackout Details,”Atlas Obscura, https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/exercise-tiger-memorial.

52 “Frank Derby Story – LST 496,” Exercise Tiger Memorial, accessed November 14, 2023, https://exercisetigermemorial.co.uk/frank-derby-story-lst-496#:~:text=LST%20496%20sank%20in%2018,the%20rest%20of%20the%20war.

53 Leon Schafer, “Leon Schafer Interview,” The Digital Collections of the National WWII Museum, accessed February 10, 2023, https://www.ww2online.org/view/leon-schafer#uss-lst-496-hits-a-mine.

54 “LST-496,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/l/lst-496.html

55 NavSource Online: Amphibious Photo: Auxiliaries and AmphibiousArchive, https://www.navsource.org/archives/10/16/1016050613.jpg. and https://www.navsource.org/archives/10/16/1016049601.jpg. Our thanks to Gary Priolo, Navsource,Project General Manager for allowing us to publish these photos here.

56 “Leon Schafer Interview.”

57 “Stripling Missing,” Fort Lauderdale News, August 31, 1944, 2; “Charles Stripling,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.abmc.gov/print/certificate/460542.

58 “D-Day (June 6, 1944),” Library of Congress, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/collections/veterans-history-project-collection/serving-our-voices/world-war-ii/d-day-june-6-1944/#:~:text=June%206th%2C%201944%3A%20More%20than,only%20to%20December%207th%2C%201941.

59 Jesse Greenspan, “Landing at Normandy: The 5 Beaches of D-Day,” The History Channel, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.history.com/articles/landing-at-normandy-the-5-beaches-of-d-day.

60 “Florida State Population Census, 1945,” database, Ancestry.com (ancestry.com: accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Charles Stripling, Broward County; “1950 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (ancestry.com: accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Willie Stripling, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

61 “Youths Entertained,” Fort Lauderdale News, June 21, 1950, 16.

62 “1950 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (ancestry.com: accessed November 14, 2023), entry for Willie Stripling, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

63 “Rev. I. G. Stripling,”News-Press, September 26, 1993; “Stripling, Mrs. Willie Clifton,” News-Press, January 25, 1990.

64 “Rev. I. G. Stripling,” 24.

65 “USS LST-496,” NavSource Online: Amphibious Photo Archive, photos, accessed on November 14, 2023, https://www.navsource.org/archives/10/16/160496.htm.

66 “Charles Stripling,” Purple Heart Hall of Honor, accessed April 21, 2023, https://www.thepurpleheart.com/roll-of-honor/profile/default?rID=5b7cb527-e530-4307-8f23-13b4968b435c; For an example of an African American Normandy Veteran denied his Purple Heart until the end of his life, see this news article: https://www.cnn.com/2021/06/23/us/ozzie-fletcher-ww2-vet-purple-heart-trnd/index.html.

67 “Stripling Missing,” Fort Lauderdale News, August 31, 1944, 2; “Charles Stripling,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed November 14, 2023, https://www.abmc.gov/print/certificate/460542.