Staff Sgt. Robert E. Prahl (April 21, 1914 – September 15, 1944)

2nd Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division

by Paiton Lackey

Early Life

Robert Earl Prahl was born in Wausau, WI, on April 21, 1914, to Otto Robert Prahl and Esther Francis Weiss, both first generation German-Americans.1 Robert’s parents had married two years prior, on June 5, 1912.2 Otto and Esther had two more children, Oron (1917) and JoAnn (1921).3 During Robert’s childhood, Esther worked from home, taking in laundry.4 Before the advent of the modern washing machine, doing the laundry was such a time consuming and physically demanding process that nearly all middle and upper class housewives sent it out to women like Esther who did the unpleasant work for them.5 Otto worked at the Marathon Papermill as a firefighter.6 The papermill employed its own firefighters because the amount of flammable paper and hazardous chemical materials created a high risk of fires, which put both the workers and the business in danger.7

Like millions of people around the world reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, Robert’s life changed dramatically in the early 1930s, while he attended high school. In his case, it appears his parents went through a tumultuous divorce. Whether the Depression played a direct or indirect role is unclear, but what we do know is that Esther cited “cruel and inhuman treatment, and overuse of intoxicating liquor” in the legal proceedings and won custody of their three children.8 Otto then counter-sued a local Wausau man, Edwin Schield, for alienation of Esther’s affections, suggesting that the two might have been having an affair.9

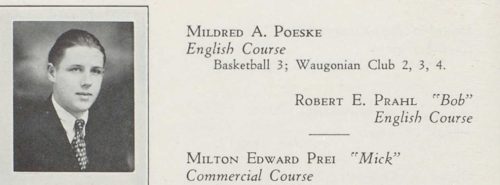

Despite the difficulties in his home life, with his parents’ divorce in 1931 and his mother remarrying Edwin Schield in 1933, Robert remained in school.10 In 1933, he graduated from Wausau High School at the age of nineteen. According to the 1933 Wausau High School yearbook, seen here, his nickname was “Bob” and he specialized in English.11 After graduating, Robert found a job at the local Sheet Metal Contracting Co., where his stepfather Edwin Schield also worked.12 Robert and his siblings lived with their mother and her second husband well into their mid-twenties, suggesting this was a close-knit family.13

On May 26, 1940, Robert married Charlotte Powell, also native of Wausau. Robert was twenty-six at the time and Charlotte was sixteen but claimed that she was twenty on the marriage license. The wedding took place in Iowa, just across the state line, possibly because the state’s marriage laws were more lenient.14 Although the wedding occurred under unusual circumstances, Charlotte’s parents announced the marriage in the local newspaper a few days after the wedding and indicated that the couple would establish a home in Wausau.15

Military Service

Robert registered for the draft on October 16, 1940. On his draft card, he listed his mother as his next of kin, despite marrying Charlotte only a few months before.16 Although this is unusual, it could be a sign of a close relationship between Robert and his mother. Sometime between October 1940 and May 1941, Robert moved to Brevard County, FL, where two of his mother’s sisters also lived.17 It is unclear if his wife Charlotte accompanied him. On May 22, 1941, the US Army called him into service, and he presented himself at Camp Blanding, FL, for training.18

Robert became a private in the 2nd Infantry Regiment of the 5th Infantry Division.19 On February 19, 1942, Robert and the 2nd Infantry sailed from New York to Reykjavik, Iceland, arriving on March 3, 1942. Life in Iceland must have been immensely different than what Robert knew in Wausau or Florida. The turbulent weather and mundane tasks affected many soldiers, who must have been cold and bored maintaining the outpost in Reykjavik. As the war raged on in Europe, the 2nd Infantry relocated to England and Ireland in early August 1943 to train for the D-Day landings. During the regiment’s time in Ireland and England, they trained in “battalion attack against fortified positions” with mock-pillboxes, in preparation for the enemy defensive structures they would encounter on the beaches of northern France.20

The first Allied landings in northern France took place on June 6, 1944. The 5th Infantry Division entered France three days later through Utah Beach, as part of the D-Day reinforcements.21 From Utah Beach, the 2nd Infantry Regiment moved inland on foot, providing reinforcements to other units as they fought to liberate the region, town by town. By August of 1944, the regiment split up. The first battalion traveled south to Nantes, about 150 miles from the English Channel, to block all roads leading north of the town and force the Germans further south, and the second battalion went about fifty miles east to the town of Angers to assist the 11th Infantry. Then the reunited regiment marched east about two hundred miles, through Chartres and the areas surrounding Paris, toward the Franco-German border. They were responsible for a task known in the military as mopping up. This meant capturing or killing any remaining enemy troops and securing any liberated territory.22

By September 1944, the 2nd Infantry crossed nearly all of France and reached the area surrounding Metz, France, about fifty miles from the German border. There, German forces tried to hold their ground and, as enemy fire rained on American troops throughout September 13 and 14, Robert’s unit could not advance any further and had to call for reinforcements.23 On September 15, 1944, Robert Prahl was killed in action, likely in the area north of Metz, after he sustained artillery wounds to the chest and face. At the time of his death, Robert was thirty years old, and had worked his way up from Private to Staff Sergeant.24 The US Army likely buried him in the vicinity of his death and reinterned him after the war.

Legacy

SSgt. Robert Prahl’s final resting place is plot J, row 7, grave 36 at the Lorraine American Cemetery and Memorial in Saint-Avold, France.25 Six days before Robert’s death, his wife, Charlotte, enlisted in the US Navy.26 Robert and Charlotte never had any children, and Charlotte must have learned of his death while she was in the service. It is unclear what position Charlotte held, but at the time women in the Naval Reserve had posts in nursing and clerical work. On rarer occasions, educated women could engage in more technical or scientific work as members of the Navy’s “Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service,” or WAVES.27 Charlotte was discharged from the Navy only three months later, on December 11, 1944.28

In 1945, Robert’s high school honored him and other alumni by dedicating pages from their yearbook to those who fought in the war.29 Robert’s mother, Esther, also lovingly carried his legacy. For the rest of her life, Esther actively participated in the local chapters of the American War Mothers, the Purple Heart Auxiliary, the Veterans of Foreign Wars Auxiliary, and the American Gold Star Mothers program.30 The American Gold Star Mothers organization arranged for mothers of servicemen killed overseas to travel abroad to visit their graves, and through this organization, Esther may have visited her son’s grave at Saint-Avold.31

Esther even served as the president of the American Gold Star Mothers Marathon County Chapter, a post from which she retired in 1958.32 It is clear from the amount of time Esther spent honoring her son and his sacrifice that Robert’s death was life-changing, and Esther took comfort in other women who had suffered a similar loss. In 1949, the Wausau chapter of the American War Mothers dedicated a stone memorial, seen here, which honored Marathon County men who gave their lives in World War II.33 Esther likely joined the push to dedicate the memorial. Esther Schield died on April 8, 1968.34 Her fellow American Gold Star Mothers led her memorial, and Robert’s legacy became her legacy.35

1 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Robert Earl Prahl, serial number 2075; “1920 US Census,” Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Otto R Prahl, Marathon County, Wisconsin.

2 “News of Society,” Wausau Daily Herald, June 5th, 1912, Newspapers.com.

3 “1930 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Robert E Prahl, Marathon County, Wisconsin. Spelling of this name varies throughout sources, some are listed as Joan, JoAnn, or Johanna. Based on her gravestone, the likely correct spelling is JoAnn.

4 “1930 US Census,” entry for Esther F Prahl.

5 Ruth Schwartz Cowan, More Work For Mother: the Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1983), 151 – 174.

6 “U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Otto R Prahl, serial number 2065.

7 James N. Hall, “Paper Mill Fires,” Fire Engineering, accessed April 5, 2021, https://fireengineering.com/leadership/paper-mills-fires.

8 “Short News Items,” Wausau Daily Herald, September 18th, 1931, Newspapers.com.

9 “Short News Items,” Wausau Daily Herald, October 10th, 1931, Newspapers.com. In the article, Otto Prahl is listed as suing an “Edwin Prahl.” This is likely a misprint due to human error, and based on Esther’s upcoming remarriage, it can be assumed that the Edwin being referred to in the article is Edwin Schield.

10 “Marathon County News,” Marshfield News-Herald, May 31st, 1933, Newspapers.com.

11 “U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Robert E Prahl, Wausau High School, Wisconsin.

12 “U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Robert E Prahl and Edwin H. Schield, Wausau; “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” entry for Robert E. Prahl.

13 “1940 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Edwin Schield, Marathon County, Wisconsin.

14 “News of Society,” Wausau Daily Herald, June 1st, 1940, Newspapers.com; “Iowa, U.S., Marriage Records, 1880-1951,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Robert Prahl. On the marriage certificate, Charlotte indicated that she would be 20 by the time of her next birthday, however, according to census records, as well as correspondence from Charlotte’s nephew’s wife, Ramona Powell, via Ancestry.com, it appears that Charlotte lied on the marriage record and was 16 at the time.

15 “News of Society,” Wausau Daily Herald, June 1st, 1940, Newspapers.com.

16 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” entry for Robert Earl Prahl.

17 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Robert E Prahl, service number 34052685. On Esther’s family in Florida, see “Mrs. Esther Schield,” The Wausau Daily Herald (Wausau, Wisconsin), April 8, 1968, Newspapers.com.

18 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” entry for Robert E Prahl.

19 “U.S., Headstone and Interment Records for U.S., Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942-1949,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Robert E Prahl.

20 US Army, Second Infantry Regiment, Fifth Infantry Division (United States Army 2d Infantry Regiment, 1946) 20 – 23.

21 “5th Infantry Division – Red Diamond,” US Army Divisions, accessed August 12, 2021, https://www.armydivs.com/5th-infantry-division.

22 US Army, Second Infantry Regiment, 33 – 41.

23 Ibid, 40 – 41.

24 “U.S., World War II Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Robert E Prahl; “US Headstone and Internment Record;” US Army, Second Infantry Regiment, 41.

25 “U.S., Headstone and Interment Records.”

26 “U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2021), entry for Charlotte Reynolds. According to social security information, Charlotte Powell went on to have several different last names, including the name Reynolds.

27 Kathleen Broome Williams, “Women Ashore: The Contribution of Waves to the US Naval Science and Technology in World War II,” Northern Mariner/Le Marin Du Nord 8, no. 2 (1998): 1-20.

28 “U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010,” entry for Charlotte Reynolds.

29 Wausau High School, The Wahiscan 1945 Yearbook, page 10, accessed March 19, 2021, https://sites.google.com/wausauschools.org/wausaueasthighschoolyearbooks. Archived by Ms. Paula Hase, Wausau East High School Librarian.

30 “News of Society,” Wausau Daily Herald, September 2, 1955, Newspapers.com; “Wausau Area Obituaries,” Wausau Daily Herald, April 8, 1968, Newspapers.com.

31 Christine M. Kreiser, “The First Gold Star Mother,” American History 47, no. 4 (October 2021): 19.

32 “Gold Star Mothers to Cheer Veterans,” Wausau Daily Herald, October 11, 1957, Newspapers.com.

33 “Marathon County Veterans Memorial: WWII,” Wisconsin Historical Markers, accessed March 19, 2021, http://www.wisconsinhistoricalmarkers.com/2014/08/marathon-county-veterans-memorial-world.html. Thank you to Gary Gisselman from the Marathon County Historical Society for clarifying the date on which the memorial was dedicated.

34 “Wausau Area Obituaries.”

35 “Helke Funeral Home,” Wausau Daily Herald, April 10, 1968, Newspapers.com.