Pvt. Orville Rex Powell (December 15, 1924 – October 2, 1944)

313th Infantry Regiment, 79th Infantry Division

by Taylor Johns and Elizabeth Klements

Early Life

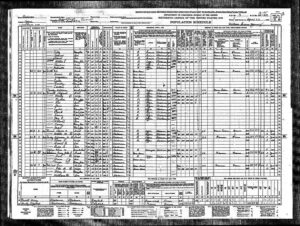

Orville Rex Powell, who often went by Rex, was born on December 15, 1924, in Coffee County, Alabama, to Clifford and Mary née Bowdoin Powell.1 Clifford and Mary married in Coffee County in 1917 at the ages of twenty-three and twenty, respectively.2 Both were born in Alabama to large farming families. While Mary grew up in Coffee County, Clifford’s family moved from Alabama to Walton, FL, in the early 1900s. By 1917, Clifford and some of his family returned to Alabama while other family members remained in Florida.3 Clifford and Mary established a farm and a family of their own in Coffee County. Orville had nine sisters and five brothers: Agnes (1918), Alice (1919), Coy (1921), Myrtice (1922), Rudolf (1923 – 1924), Samuel (1926), Lydia Marie (1927), Omah (1929), Laura (1931), Joy (1933), Roland (1936), Nancy (1939), and Joan (1940).4 Such a large family, not uncommon for the time, would have been useful as extra hands on the farm. While the children doubtless worked on the farm, they also attended school – boys and girls alike – so that they could read and write. At least one daughter received a high school education, at a time when only one in eleven rural Alabama children attended high school.5

The Powell children’s access to education and the fact that Orville Powell owned his own farm, as seen in the 1940 census, suggests the Powell’s had a degree of prosperity during the difficult years of the 1930s. The Great Depression affected every level of commerce in the country, and the agricultural south further suffered from the boll weevil infestation which decimated its cotton industry by the 1920s. Luckily, most farmers in Coffee County, including the Powells had started growing peanuts, a switch of crops G.W. Carver, at the Department of Agriculture at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institut developed and supported with the aim to increase southern farmer’s revenues. By 1919, Coffee County became the largest producer of peanuts in the country and began to diversify to other cash crops such as potatoes, sugar cane, sorghum, and tobacco.6 Orville’s farm likely grew peanuts or some of these other cash crops.

Between 1940 and 1942, the teenaged Clifford moved to the city of Ocoee, in Orange County, FL.7 Clifford had some aunts and uncles scattered across Florida, but none near Ocoee, an all-white community after the Ocoee Massacre of 1920 when white residents murdered and drove out the town’s black inhabitants.8 Clifford probably moved to Ocoee for its proximity to Dr. Philip’s orange groves and refinery. Dr. Phillips was known for owning a substantial portion of the orange groves in Central Florida and changing the citrus industry forever by creating “flash” pasteurization which gave orange juice a longer shelf life. By 1940, he dominated the orange industry in Central Florida, and his support and philanthropy helped other Central Florida businesses to grow as well.9 Like many others in the area, Orville worked for Dr. Philips, either in the orange groves or the processing plant.10

Military Service

The 1940 Selective Training and Service Act required every adult man to register for the draft, which Orville did in December 1942, a few weeks after his eighteenth birthday.11Half a year later, his number came up, and Orville reported to Camp Blanding for training on June 26, 1943.12 Located in Starke, FL, Camp Blanding had been a training reserve station for the Florida National Guard. In 1940, the US Army converted it into a federal training camp and expanded it to accommodate up to two complete infantry divisions at a time, about 30,0000 men.13 After the initial training, Powell joined the 313th Regiment of the 79th Infantry Division, which was known as the “Cross of Lorraine” Division for its participation in the Meuse-Argonne battle in the Lorraine region of France during World War I.14

The 79th trained at Camp Blanding before moving to field training in Tennessee and then desert maneuvers in Arizona. In December 1943, the 79th transferred once again to Camp Phillips in Kansas to train under winter conditions. During this winter, Orville, probably not used to the conditions, caught a bad cold for which he was hospitalized.15 The US Army wanted these new recruits as prepared as possible to take the place of the soldiers who had fallen in overseas combat operations already underway. In April 1944, the 79th Division crossed the Atlantic, landing at Liverpool, England, in the middle of the same month.16

In England, the 79th prepared for the Allied invasion of France, scheduled for D-Day, June 6, 1944. Having ousted the German forces in northern Africa and almost all of Italy by the spring of 1944, the Allied leaders prepared for the liberation of France. The first Allied landings took place on the coast of northern France, from which point the Allied troops pushed inland toward Paris. Between April and June, the 79th trained for amphibious operations and for attacks on fortified areas to prepare for the inevitable encounter with the German troops in northern France.17

Orville and the rest of the 79th Division landed in the second wave of attacks on Utah Beach, Normandy between June 12 and 14, alongside the 4th, 90th, and 9th Infantry Divisions, which altogether made up the American VII Corps. The US military command instructed this Corps to seize the port city of Cherbourg and its surrounding area. Cherbourg’s capture was vital to the Allies’ overall success allowing control on supplies’ transportation. The assault began on June 19, 1944, and lasted until June 26, when the German troops defending Cherbourg finally surrendered. Orville’s regiment, the 313th, played a key role in this engagement, taking the brunt of the attack as the Corps took Fort du Roule, the last German stronghold defending the city.18

For the rest of June and July, the 79th Division pushed across northern France, at first encountering strong enemy resistance, and then moving quickly with less difficulty toward the Paris region. In early August, the 79th was about to reach Versailles when the military command ordered it to take the heights overlooking Mantes-Gassicourt, north of Paris, which would block the last escape route for Germans trapped by the Allied troops in northern France.19Throughout August, the 79th fought to take these heights and then cross the river Seine in face of German resistance.20

At the end of August, the US military leaders reassigned the 79th Division to the XIX Corps near the Franco-Belgian border. Then, throughout September, the 79th Division fought along a forty-mile front in the Lorraine region, liberating Charmes, Poussay, Ambacourt, Neufchateau, and Luneville. On September 28, 1944, the division began the attack on their next objective, the Parroy Forest. The new terrain was especially challenging to the men of the 79th and the German resistance was fierce. A captured German officer in the engagement reported that the German troops had received a direct order from Hitler to hold the forest at all costs, because “he, Hitler, had fought here in the last war and had attached a high sentimental value to this area.”21 By October 2, the Division had advanced a third of the way through the forest. The 313th regiment spent the day reorganizing and patrolling when the sporadic enemy artillery fire struck and killed Pvt. Orville Powell.22 He was nineteen years old.

Legacy

The battle for the Parroy Forest ended with an Allied victory at the end of October, and the 79th Division received some well-earned rest before pushing further East. The Division defended the Allies’ hold of the Moder River in the North of Alsace over the winter of 1944 – 1945, crossed the Rhine River in April, and helped clear a pocket of resistance in the Ruhr valley. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the Division remained on occupation duty until it was deactivated and sent back to the US.23In 1946, the French Provisional Government awarded the 79th Division with the Croix de Guerre with Palm in recognition of its “splendid endurance and exceptional fighting zeal” in the forest of Parroy and in liberating Baccarat, Phalsbourg, and Saverne.24

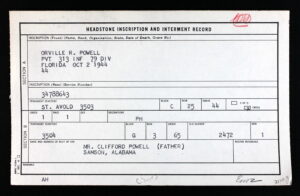

His fellow soldiers buried Pvt. Powell at a temporary cemetery in Lay-Saint-Remy near his place of death, and, after the war, the US Army reinterred him at the Lorraine American Cemetery in St. Avold, in block C, row 25, grave 44.25 As seen in his headstone inscription and internment record, Powell earned a posthumous Purple Heart, a symbol of his camaraderie and bravery, awarded to soldiers who are injured or killed in action while defending the United States.26He was survived by his father and mother, who passed away in 1962 and 1986 respectively, four brothers and seven sisters.27 The war took away Powell’s chance to grow old alongside his family, but his service and sacrifice helped ensure their future safety and happiness.

1 “U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 22, 2021), entry for Orville Rex Powell, Ocoee, Orange County, Florida.

2 “Alabama, Coffee County, Marriages, 1830- 1957,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed February 22, 2021) entry for Clifford Powell and Mary Bowdoin, Coffee County, Alabama.

3 “1910 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed January 26, 2022) entry for Orville Clifford, Walton County, Florida, and for Mary Bowdoin, Coffee County, Alabama; “Obituaries: Clifford Powell,” Geneva County Reaper, August 2, 1962, page 8, Newspapers.com.

4 “1930 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed January 26, 2022) entry for Orville Clifford, Coffee County, Alabama; “1940 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed January 26, 2022) entry for Orville Clifford, Coffee County, Alabama. For Rudolf Powell, see “Rudolf Douglas Powell,” Find a Grave, accessed January 26, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/123772328/rudolf-douglas-powell.

5 “1940 US Census;” Gordon Harvey, ”Public Education in the Early Twentieth Century,” Encyclopedia of Alabama, accessed January 26, 2022, http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2601.

6 Lorraine Boissoneault, ”Why an Alabama Town Has a Monument Honoring the Most Destructive Pest in American History,” American South, May 31, 2017, accessed January 26, 2022, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/agricultural-pest-honored-herald-prosperity-enterprise-alabama-180963506/.

7 “U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card.”

8 “Obituary: Orville Powell;” Carlee Hoffmann and Claire Strom, “A Perfect Storm: The Ocoee Riot of 1920,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 93, no. 1 (Summer 2014): 25 – 43; “Bending Toward Justice: Voting Rights and Voter Suppression,” RICHES, accessed October 14, 2022, https://bendingtowardjustice.cah.ucf.edu/

9 Joy Wallace Dickinson, “Doctor Philips: The Real Deal,” Orlando Sentinel, May 1, 2007, accessed January 26, 2022, https://www.orlandosentinel.com/orl-doctorphillips-history-story.html; “Bittersweet: The Rise and Fall of the Citrus Industry in Florida,” Florida Memory, accessed January 26, 2022, https://www.floridamemory.com/learn/exhibits/photo_exhibits/citrus/.

10 “U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card.”

11 “U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card.” (ibid)

12 “U.S., WWII Army Enlistment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 22, 2021), entry for Orville R. Powell, service number 34788643.

13 “History of Camp Blanding,” Camp Blanding, accessed March 18, 2021, https://fl.ng.mil/Camp-Blanding/Pages/History.aspx, George E. Cressman Jr., “Camp Blanding in World War II: The Early Years,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 97, No. 1 (Summer 2018), 44.

14 US Army, The Cross of Lorraine: a Combat History of the 79th Infantry Division, June 1942-December 1945 (1946), 8 – 9, https://issuu.com/79thdivision/docs/ww2-history_of_the_79th.

15 “U.S., WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-54,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 22, 2021), entry for Powell, Orville R., service number 34788643, February 1944.

16 US Army, The Cross of Lorraine, 9.

17 US Army, The Cross of Lorraine, 9; William M. Hammond, “Normandy, 6 June – 24 July 1944,” US Army Center of Military History, accessed February 10, 2022, https://history.army.mil/html/books/072/72-18/index.html.

18 US Army, The Cross of Lorraine, 18 – 27.

19 US Army, The Cross of Lorraine, 28 – 47.

20 US Army, The Cross of Lorraine, 47 – 49.

21 US Army, The Cross of Lorraine, 69.

22 Sterling A. Wood, History of the 313th Infantry in World War II (Washington: Infantry Journal Press, 1947), 124; Staff Group C, Section 11, CSI Battlebook 11 – C: Foret de Parroy (Fort Leavenworth: Combat Studies Institute, 1984), 59 – 61; “U.S., WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-54,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 22, 2021), entry for Powell, Orville R., service number 34788643, October 1944.

23 “79th Infantry Division – Cross of Lorraine,” US Army Divisions, accessed January 28, 2022, https://www.armydivs.com/79th-infantry-division.

24 Wood, History of the 313th Infantry, 203.

25 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Record,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 4, 2021), entry for Orville R. Powell, service number 34788643.

26 Fred Borch, “The Purple Heart – The Story of America’s Oldest Military Decoration and Some Soldier Recipients,” accessed April 4, 2021, www.Armyhistory.org.

27 “Pvt. Orville Rex Powell,” Find a Grave, accessed February 10, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56659665/orville-rex-powell. This link also provides two pictures of Pvt. Orville Rex Powell which we have not been able to verify.