PFC Rubbie McKnight (April 22, 1912—February 22, 1946)

3985 Quartermaster Truck Company

by Jacob November and Elizabeth Klements

Early Life

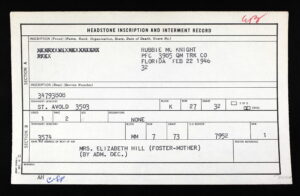

Rubbie McKnight was born on April 22, 1912, in Willacoochee, a small town in rural southeast Georgia.1 Not much is known about his parents. They likely worked as sharecroppers, like many other African Americans working in agriculture in the Jim Crow south.2 Rubbie only appeared in the census records as an adult, and his internment record, seen here, indicated that his nearest relation was Mrs. Elizabeth Hill, “foster mother.”3 The foster system as we know it today emerged in the 1930s and 1940s from a patchwork of private child protection and placement agencies which underserved and ignored African American populations, especially in the south. As a result, very few African American children entered foster homes through fostering agencies until the second half of the twentieth century. Instead, black communities relied on informal kinship networks to care for children in need.4 Rubbie may have been an exception, as a young African American boy officially placed into a foster home, or Mrs. Elizabeth Hill may have belonged to such a kinship network with Rubbie’s parents and took him in after they could no longer care for him.

Despite the challenges Rubbie faced as a child, he received a grammar-school education and could read and write.5 He became a legal adult in 1930, and, by 1935, was living in Gainesville, FL.6 This was the beginning of the Great Depression, which disproportionately affected African Americans, especially those in the South.7 Rubbie may have already lived in Florida, or moved to Florida once he reached maturity, but it seems clear he sought the work opportunities. Gainesville was home to the University of Florida, which, by the 1930s, became the center of the region’s economy and which helped Gainesville weather the economic instability of the 1930s far better than other Florida cities.8 Like many Gainesville residents, Rubbie found work at the University of Florida. By 1940, he was an assistant at the University’s Infirmary, which provided healthcare for students on campus.9 Rubbie worked in the same building that, with some renovation, still houses UF’s Student Healthcare Center.10 As in all industries in Jim Crow south, discrimination limited the jobs that Rubbie could have performed at the Infirmary. Depending on the level of care the infirmary provided to the students, Rubbie may have worked as an orderly, assisting in everyday patient care like changing sheets and bedpans, or he may have had a more janitorial role.11

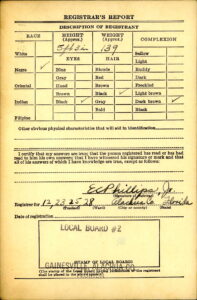

By 1940, Rubbie met and married a woman named Ethel, who was from Tallahassee, FL, and who worked as a maid and cook for a private family.12 Their relationship, however, seems to have ended that year. When Rubbie registered for the 1940 draft, he listed his next-door neighbor, Mrs. Mattie Grey, as his closest contact, rather than his wife Ethel or Mrs. Hill. This draft card, shown here, provides the only known record of what Rubbie might have looked like. It describes him as 5’3”, 139 pounds, with “black hair, black eyes, [and a] dark brown complexion.”13 Between April 1940, when the census worker recorded Rubbie’s information, and October 1940, when he registered for the draft, Rubbie moved to a different address in Gainesville and started a new job, at the College Inn, a restaurant on the University campus.14 Between 1940 and 1943, Rubbie moved again, this time to Jacksonville, and worked there as a laborer for the Royal Crown Bottling Co.15

Military Service

Although Rubbie registered for the draft in 1940, the US Army did not call him to service until 1943. The 1940 Selective Service Act officially prohibited discrimination in the military, but it occurred in practice. The draft boards tended to call up African American men later than their white counterparts during the war, despite the Army’s great need for manpower, out of racist fears and prejudices about arming African American soldiers. For the same reasons, the US military usually assigned African American servicemen to service and support units rather than combat units.16 Rubbie entered Camp Blanding, FL, for training on October 6, 1943.17 Both the Army’s unofficial policy of segregation and local Jim Crow laws influenced military training. The camp authorities quartered the African American servicemen at the most undesirable parts of the camp and gave them the most menial duties in the camp, such as cooking and cleaning.18 In early 1944, Rubbie finished training and the Army assigned him to the 3135th Quartermaster Service Company, an all-black unit in the Quartermaster Corps.19

Because the US military leaders wanted to avoid putting African American soldiers into combat units, most African American soldiers in World War II belonged to the Quartermaster Corps. There, they served under a white officer and performed non-combat duties, such as cooking, manual labor, transportation, and more.20 As Rubbie’s unit was a “Service” company, it is likely that the 3135th did mostly manual labor. It must have been frustrating for these young men who wanted to fight for their country and prove themselves, only to face the same unfair pressures and institutional racism in the military that they faced at home.

Although military leaders saw it as second-class work suitable for second-class citizens, the Quartermaster companies played an integral role in the war effort. Rubbie’s company shipped out to France and supported American troops during the Northern France campaign, from July 25 to September 14, 1944. During this period, Allied troops pushed across northern France toward the Franco-German border in the months after the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944.21 After the Northern France campaign, something must have happened as Rubbie was reported as a deserter in January 1945.22 We are not sure why Rubbie went absent without leave (AWOL), and as we do not have any records that indicate he faced disciplinary action.23 It is possible he got temporarily separated from his unit and someone reported him as having deserted. This is all the more likely because he disappeared during the Battle of the Bulge, a German counteroffensive in the Ardennes Forest during the winter of 1944 – 1945. The bitterly cold and snowy weather, the difficult terrain, and the moving enemy lines all added to the chaos of a combat zone, and it would have been easy in these conditions for a soldier to lose contact with the rest of his company.24

At some point after his return, the US Army promoted Rubbie to Private First Class and reassigned him to the 3985th Quartermaster Truck Company, which was responsible for transporting men and materials to the front lines.25 The 3985th participated in the Battle of the Bulge, after which it moved with Allied troops into Germany during the Rhineland campaign.26 The 3985th entered Germany on May 2, 1945, five days before Germany surrendered.27 After its defeat, the four Allied powers divided Germany into four zones, one each for the United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union. Rubbie’s unit remained in the US sector in southern Germany.28

While Germany had been the aggressor during the war, by 1945 its infrastructure, cities, and people were in tatters from years of wars and the intense Allied bombings. Like other Quartermaster units, the 3985th helped in the rebuilding efforts, likely helping transport supplies as a Truck Company. African American soldiers made up a large part of the occupying and rebuilding force in US-occupied Germany. White soldiers got preferential treatment on transport ships after the war, and so many came home before their black counterparts. While some black soldiers resented this, others re-enlisted so that they could remain in Germany. As they had done throughout the war, the US military in Germany discriminated against the African American soldiers there. The leaders assigned them to the countryside, rather than important cities, where they would be less visible. Some army units even imposed segregation in certain German towns, by forcibly removing African American soldiers from establishments frequented by white soldiers. Despite this, some black soldiers preferred to stay in Germany, because the discrimination was not as pervasive as in Jim Crow South.29

Five and a half months after the war ended, Private First Class Rubbie McKnight passed away on February 22, 1946, from unknown causes. He was thirty-three years old.30 Rubbie could have fallen victim to any number of the dangers that plagued the occupying troops in postwar Germany. Unstable buildings collapsed, undetonated bombs exploded, and terrible conditions lead to frequent fires.31 Given the tensions in occupied Germany, Rubbie’s death could also have been the result of racially-motivated violence.32

Legacy

Rubbie’s fellow soldiers buried him in a temporary cemetery and later reinterred him at the Lorraine American Cemetery in France, near the German border. This American Battle Monuments Commission Cemetery, dedicated in 1960, is the final resting place of 10,486 American servicemen, many of whom died in Germany during the US occupation.33 Rubbie’s internment card, shown earlier, highlights how alone this thirty-three-year-old had been during his life. The Army named Elizabeth Hill as his next of kin, despite the fact that Rubbie indicated in his draft registration forms that his friend and neighbor Mattie Grey was his closest contact.34 The Army did not have an address for Elizabeth Hill in its records, meaning that nobody received word of his reinterment. Rubbie’s death was not even reported in the World War II Honor List of Dead and Wounded, because it occurred one month after the list’s cut-off date of January 1946.35

Rubbie McKnight fought against adversity through his whole life. As an African American orphan who grew up in the segregated south, he became an adult even as his nation sank into the Great Depression. He found stability working at the University of Florida before the Army called him to serve his country in the final years of World War II. He played a vital role in securing victory for the Allies and rebuilding the home of the vanquished, all the while facing discrimination. His story stands as a testament to the struggles of the black community which strove against the unjust system of segregation. Rubbie McKnight was a hero and a man who deserves to be honored and remembered. We do both.

1 “WWII Draft Registration Cards,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed February 1, 2021), entry for Rubbie McKnight, serial number 1694; “Willacoochee History,” Willacoochee GA, accessed September 23, 2021, https://willacoochee.com/Willacoochee_History.html.

2 W. Fitzhugh Brundage, “A Portrait of Southern Sharecropping: the 1911-1912 Georgia Plantation Survey of Robert Preston Brooks,” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 77, no. 2 (Summer, 1993): 367-381.

3“U.S., Headstone and Interment Record,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 1, 2021), entry for Rubbie Mc Knight, 34793808.

4 Catherine E. Rymph, Raising Government Children: a History of Foster Care and the American Welfare State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 34 – 36, 124 – 126.

5 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed March 23, 2021), entry for Rubbie McKnight, service number 34793808.

6 “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 23, 2021), entry for Rubbie McKnight, Gainesville, Alachua, Florida. The 1940 census indicated that Rubbie lived at the same address in 1935.

7 Raymond Wolters, Negroes and the Great Depression: The Problem of Economic Recovery (Westport: Greenwood Publishing Corporation, 1970), 7-8.

8 Ben Pickard, “History of Gainesville,” City of Gainesville, accessed September 16, 2021, http://www.cityofgainesville.org/Community/AboutGainesville/History.aspx.

9 “1940 U.S. Census.”

10 See images of the infirmary in the 1930s here: “Photograph 423: University Archives Photograph Collection,” University of Florida Digital Collections, accessed September 23, 2021, http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00029651/00001.

11 David Cavanaugh, “UVA and the History of Race: Confronting Labor Discrimination,” UVA Today, March 18, 2021, accessed April 22, 2021, https://news.virginia.edu/content/uva-and-history-race-confronting-labor-discrimination.

12 “1940 US Census,” entry for Ethel McKnight, Gainesville, Alachua, Florida.

13 “WWII Draft Registration Cards.”

14 The current UF Emerson Alumni Hall is currently located where the College Inn used to stand. To see photos of the College Inn in the 1930s, see “Photograph 2380: University Archives Photograph Collection,” University of Florida Digital Collections, accessed September 23, 2021, http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00030420/00001.

15 “Ohio and Florida, U.S., City Directories, 1902-1960” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed February 11, 2021), entry for Rubbie McKnight, Jacksonville, Duval, Florida.

16 Neil A. Wynn, The African American Experience during World War II (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010), 44.

17 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records.”

18 Jon Evans, “The Origins of Tallahassee’s Racial Disturbance Plan: Segregation, Racial Tensions and Violence During World War II,” Florida Historical Quarterly 79, no. 3 (Winter 2001): 346 -364.

19“U.S., WWII Army Deserters Pay Cards, 1943-1945” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed February 11, 2021), entry for Rubbie McKnight, service number 34793808.

20 Bryan D. Booker, African Americans in the United States Army in World War II (Portland: McFarland & Co., 2008), 60. For more examples of different possible duties, see chapter 4, “Combat Service Support Units.”

21 US Army, Unit Citation and Campaign Participation Credit Register (Washington D.C.: Department of the Army, 1961), 459; David W. Hogan, “Northern France,” accessed September 24, 2021, https://history.army.mil/brochures/norfran/norfran.htm.

22 “U.S., WWII Army Deserters Pay Cards, 1943-1945” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed February 11, 2021), entry for Rubbie McKnight, Army Serial Number 34793808.

23 When a soldier deserts and later returns to active service, he is officially AWOL, not a deserter.

24 Hugh M. Cole, The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge (Washington D.C.: Department of the Army, 1965), 649 – 673.

25 “U.S., Headstone and Interment Records.”

26 U.S. Army, Unit Citation and Campaign Participation Credit Register, 489; Ted Ballard, “Rhineland Campaign,” accessed September 24, 2021, https://history.army.mil/brochures/rhineland/rhineland.htm.

27 U.S. Army, Unit Citation and Campaign Participation Credit Register, 489.

28 Earl F. Ziemke, The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany, 1944-1946 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 1990), 109 – 129.

29 Alexis Clark, “When Jim Crow Reigned Amid the Rubble of Nazi Germany,” The New York Times Magazine, February 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/19/magazine/blacks-wwii-racism-germany.html.

30 “U.S., Headstone and Interment Records.”

31 Elizabeth Heineman, “The Hour of the Woman: Memories of Germany’s ‘Crisis Years’ and West German National Identity,” The American Historical Review 101, no. 2 (Apr., 1996): 374.

32 Alexis Clark, “When Jim Crow Reigned Amid the Rubble of Nazi Germany.”

33 “Lorraine American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed April 22, 2021, https://www.abmc.gov/Lorraine.

34 “U.S., Headstone and Interment Records.”

35 “World War II Honor List of Dead and Missing,” database, National Archives (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/305285: accessed September 24, 2021), entry for State of Florida.