2nd Lt. Richard Lee McClintock (April 15, 1914 – January 5, 1945)

276th Infantry Regiment, 70th Infantry Division

by James Bentley and Elizabeth Klements

Early Life

Richard Lee McClintock was born to Frederick and Edith McClintock on April 15, 1914, in Greenville, SC.1 Frederick was an insurance agent, and moved his family across the US several times throughout Richard’s youth. Both Frederick and Edith were from Virginia, and lived there for a few years after they married, during which time they had Fred Jr. (1911) and Margaret C. (1912). The family then moved to South Carolina, where they had Richard in 1914, before moving across the country to Colorado.2 There, the couple had their two youngest children, Mary Virginia (1917) and Charles W. (1921). Sometime between 1921 and 1930, Frederick moved his family a final time, to Tampa, FL.3

Frederick died in Tampa in 1930, at the age of fifty-four.4 His death must have introduced financial complications for the rest of the family, as Edith, who had never worked during her marriage, took a job as a housekeeper, as did her sister-in-law who had been living with the family since the 1930s. The oldest son, Frederick Jr., moved back into his mother’s home with his wife and young daughter, likely to provide financial support. The family also took in a boarder, a dressmaker named Mrs. Robbie.5 Despite this upheaval, McClintock successfully finished high school and found work as a fireman on a cargo ship based at Port Tampa Bay.6 He married Edna Wittman in 1931, at the age of seventeen, but they divorced a year later, and he remarried in 1938 to Jewell Price.7 By 1940, McClintock left the shipping industry and worked as a salesman for Armour and Co., an important firm in the meatpacking industry, while Jewell worked as a registered nurse.8

Military Service

McClintock registered for the draft in 1940 and was called to service in December of 1942. Likely due to his experience as seaman, the US Army assigned him to the Coast Artillery Anti-Aircraft Division, where he entered as a Warrant Officer.9 McClintock remained in this division for two years, where he rose to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. In July 1944, the Army transferred him from this division to the 276th Regiment of the 70th Infantry Division.10

The Army activated the 70th Infantry Division in June, 1943. Its purpose was to support and replace American troops already in combat in Western Europe.11 Because the Army intended this division to go to the areas of most intense combat in Europe, it trained for over a year – from June 1943 to December 1944 – before shipping out.12 This need for well-trained men may also explain why the Army transferred a seasoned officer like McClintock to the division. When he arrived in July, he became the leader of the 3rd Platoon, Company A, 276th Regiment.13

McClintock’s regiment shipped out in December 1944, and arrived at the port of Marseille, in southern France, at the end of the month. Allied forces had landed there a few months earlier and had pushed the Germans back toward France’s northeastern border by the time McClintock’s regiment arrived. It was on this border in the winter of 1944 that the German forces made their final stand. On December 16, they launched an attack to break through Allied lines in the Ardennes Forest near the Franco-Belgian border, in what became the lengthy Battle of the Bulge. Allied leaders immediately diverted troops from the Franco-German border to assist in the Battle of the Bulge, and created Task Force Herren, a body of various infantry regiments, to hold the now-weakened Allied line on the Franco-German border.14

The Army assigned McClintock’s regiment to Task Force Herren. From Marseille, it traveled North across the country to the town of Wingen-sur-Moder. This was a small town in the Northern Vosges area, in Alsace near the Franco-German border, but it was critical to the Allied war effort in the area because it was part of the main supply route for the US 7th Army.15 McClintock’s regiment arrived there on January 2, 1945, and set up defensive positions about 200 yards south of the town. On the dawn of January 4, German forces launched a surprise attack and quickly took the town. This attack was part of “Operation Nordwind,” the Germans’ last major offensive of the war, in which they tried to break through the Allied lines in the Alsace-Lorrain area, while also drawing Allied troops away from the action in the Ardennes.16

After taking Wingen-sur-Moder, the Germans prepared to move south to the town of Saverne, but Company A of the 276th Regiment stood in their way. Not expecting an attack, the company had been resting in the shelter of the forest that lay south of the town. After the initial confusion, Company A received orders to move to the foxholes that they had dug out the day before and hold their ground. McClintock’s 3rd Platoon had to move across a hundred yards of exposed ground to reach their foxholes, but a German machine-gunner stationed at the edge of the village rained fire on them every time they attempted to cross it. McClintock decided to silence this machine-gunner himself. He ordered his men to distract the gunner by firing at his position, while he tried to get close enough to the gunner to launch a hand grenade at him. As McClintock made his way through the heavy snow toward the village edge, two other German machine gunners noticed his approach caught him in their crossfire.17 According to an official Army statement: “the mortar fire he directed at the sacrifice of his life successfully knocked out the enemy positions. His intrepid actions enabled his command to advance and participate in the capture of the town.”18

Legacy

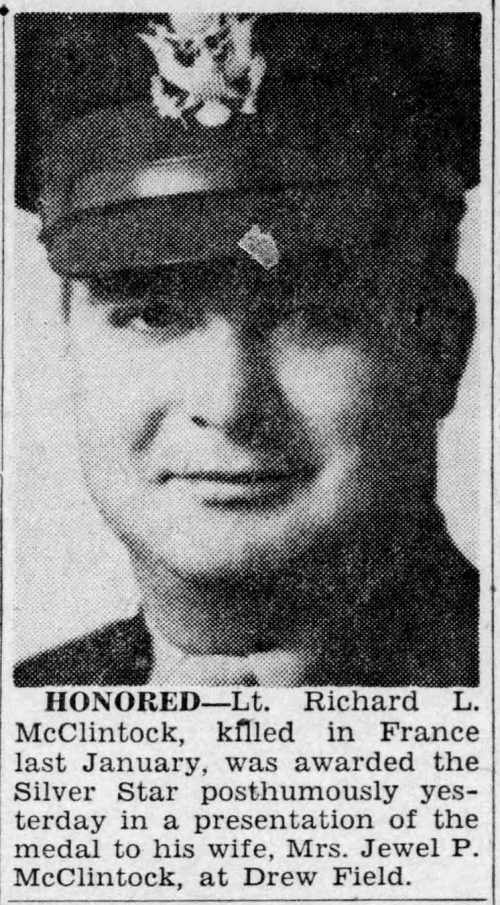

2nd Lt. McClintock died on January 5, 1945. His brothers in arms fought for three more days to retake the town. By stopping the German offensive there, McClintock’s regiment kept the Allied supply lines intact, thus helping to foil a major objective of “Operation Nordwind.”19 For his bravery in this battle, McClintock’s commanders recommended him for the Distinguished Service Cross. In the end, the Army awarded him the Silver Star Medal for gallantry in action and a Purple Heart for his death.20 They buried him at the Epinal American Cemetery in France.21

Back in Tampa, FL, McClintock left behind his widow, Jewell McClintock, as well as his mother, his two brothers, and two sisters. In January, the local papers published obituaries mourning the loss to his family and his community.22 Later that year, Brig. General Y. H. Taylor presented McClintock’s Silver Star to Jewell at a ceremony at the Drew Field in Tampa.23

1 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/12594207:2238: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard Lee McClintock; “1920 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard Lee McClintock.

2 “1920 U.S. Census.”

3 “1930 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard Lee McClintock.

4 “Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Frederick W. McClintock.

5 “1935 Florida State Census, ” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard L. McClintock.

6 “U.S., Applications for Seaman’s Protection Certificates, 1916-1940,” database, Ancestry (https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?dbid=61257&h=82337&indiv=try: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard L. McClintock; “Killed 30 Days After Departure,” The Tampa Times (Tampa, Florida), January 22, 1945.

7 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard L. McClintock and Edna Wittman, and entry for Richard L. McClintock and Jewell Price; “Florida, U.S., Divorce Index, 1927-2001,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard L. McClintock and Edna McClintock.

8 “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard McClintock; for Armour and Co., also see “Plankington, John 1820-1891,” Dictionary of Wisconsin History, https://web.archive.org/web/20131030074914/http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/dictionary/index.asp?action=view&term_id=1725&term_type_id=1&term_type_text=People&letter=P: accessed June 1, 2021.

9 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard L. McClintock; “Killed 30 Days After Departure.”

10 “Killed 30 Days After Departure;” “U.S., Headstone and Internment Records,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 1, 2021), entry for Richard L. McClintock.

11 Frank H. Lowry, Company A, 276th Infantry in World War II (Modesto, CA, 1991), 5, accessed at Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/image/306323942: accessed June 1, 2021).

12 Ibid, 5 – 29.

13 Ibid, 16.

14 Ibid, 46 – 49.

15 Ibid, 71.

16 Ibid, 65 – 66, 70.

17 Ibid, 78 – 79.

18 “War Heroes Get Medals at Drew,” The Tampa Times (Tampa, Florida), October 26, 1945.

19 Lowry, Company A, 114.

20 U.S. Army, “276th Infantry, Unit History,” database, Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/image/313747582: accessed June 2, 2021), page 5.

21 “U.S. Headstone and Internment Records.”

22 “Killed 30 Days After Departure.”

23 “War Heroes Get Medals at Drew.”