SGT. John R. Maddox (February 7, 1922 – September 17, 1944)

10th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division

by Tyler Patterson and Sebastian Garcia

Early Life

John Robert Maddox was born in Wauchula, FL, on February 7, 1922, to Walter and Lucille Maddox.1 John was Walter and Lucile’s second child after Walter Jr. (1915).2 John’s father, Walter, born on August 16, 1890, also hailed from Wauchula, FL, an agricultural community about sixty miles east of Sarasota; he was the second oldest son of five born to Alexander and Jane Maddox.3 In 1917, Walter registered for the World War I draft but was likely not called as he was already married with a child.4 John’s mother, Lucille Maddox, was the oldest daughter of four, born on May 29, 1894, to John L. and Jesse L. Skipper.5

By the 1930s, the Maddox family moved from Wauchula to Avon Park, Highlands County, FL. The move about a hundred miles northeast may have stemmed from the ongoing nationwide economic struggles of the Great Depression. In Avon Park, Walter became a self-employed broker for fruits and vegetables. Produce brokers negotiated contracts between farmers or producers of agricultural products and buyers. While Walter worked, Lucille cared for the family.6 Around 1935, the family moved southeast to rural Polk County, FL, before ultimately returning to their original hometown of Wauchula, in Hardee County, FL, five years later. Perhaps selling fruits and vegetables proved inadequate as by the early 1940s, Walter had taken a job as a truck driver.7 A sweeping infestation of Mediterranean insects damaged and restricted agricultural exports from Florida during this time, which could further explain the failure of Walter’s fruit and vegetable occupation.8 John’s father seemed to switch jobs often, likely due to the economic crisis, precipitating frequent family moves.

From 1932 to 1934, when the Depression reached its climax, twenty to twenty-five percent of Americans were unemployed on average.9 Given that Floridians already experienced harrowing economic conditions with the Florida Land Bust of the mid-1920s, the Depression’s impact remained limited, especially compared to other states. Real per capita income from 1929 to 1934 in Florida ranked higher than the United States average, and per capita farm earnings were also significantly elevated compared to the rest of the country.10 The expansion of the tourism industry in Florida enabled the state’s relatively rapid economic recovery and sustained strength, which further fueled financial growth throughout the state after 1933.11

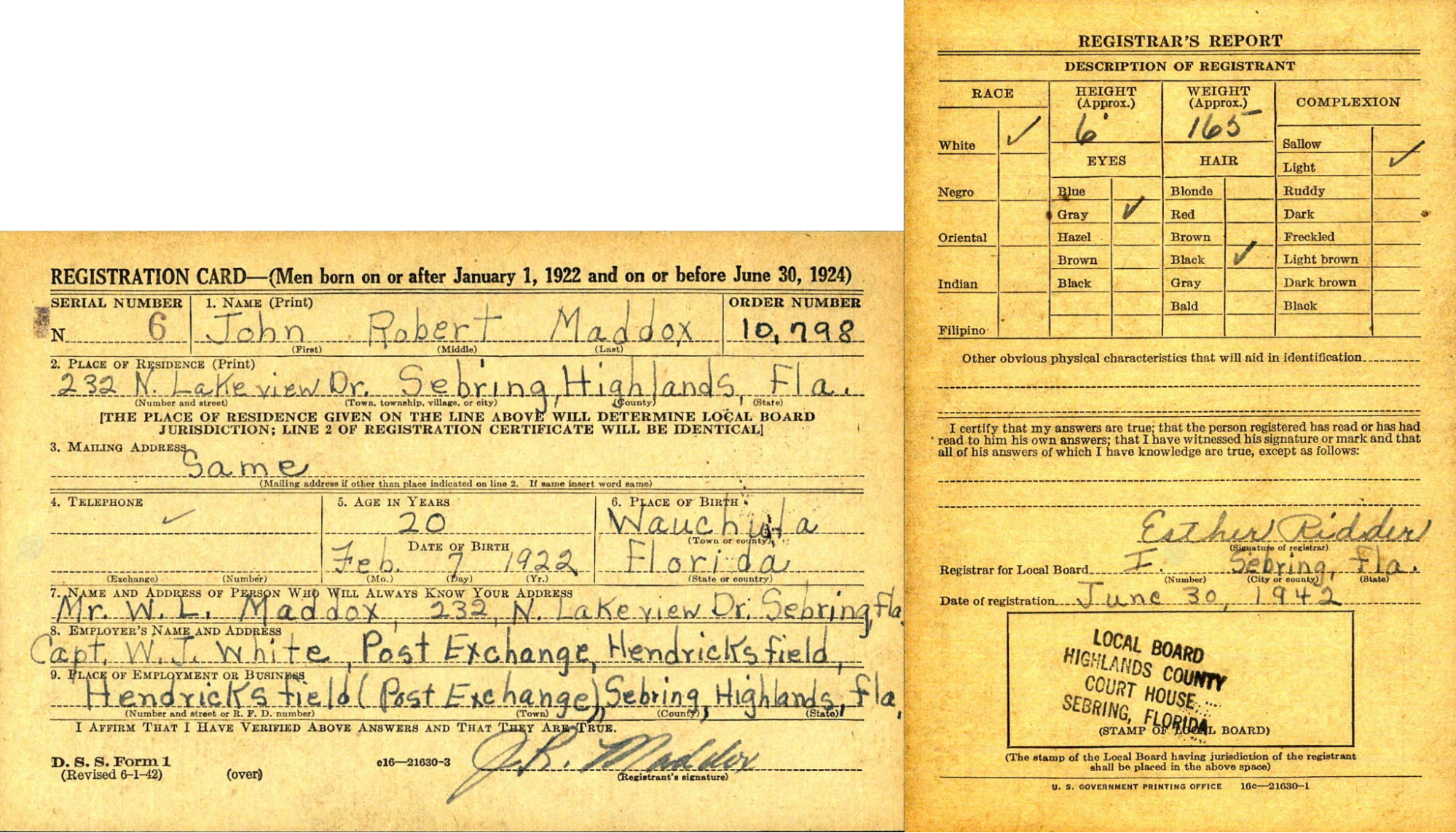

John Maddox spent his teenage years and young adult life at the height of the Great Depression in a family that appears to have struggled. Yet, while many his age had to leave school to help their families, Maddox completed four years of high school education from Wauchula High School.12 John moved out of the family home around 1942 and settled in Sebring, Highlands County, FL. There, he worked for the US Army as a civilian assistant manager of the post exchange at Hendricks Field, a recently constructed military airfield.13 At Hendricks Field, he registered for the draft on June 30, 1942, as seen here.14 His brother, Walter Jr., also lived in the area, in Avon Park, for at least the past two years, working as a salesperson.15 Around this time, John met and married Helen Roberts, who, after completing her education at Marietta Hospital Training School, GA, worked as an “operating room nurse” at Weems Hospital in Sebring, FL. Judge McNicholas authorized the marriage of John and Helen Roberts at the Sebring courthouse on October 13, 1942.16

Military Life

At the age of twenty-one, on February 20, 1943, Maddox entered the Army at Camp Blanding, FL.17 He followed in the footsteps of his brother Walter Jr., who preceded him by almost three years, enlisting in the US Army in November 1940, just a few days after he filled out the draft card.18

Camp Blanding became a major US Army training camp throughout World War II. Located southwest of Jacksonville in Starke, FL, it trained over 800,000 men, with the lion share going through once it became one of the Army Infantry Replacement Centers (IRTC) in 1943. At any one time, it housed, fed, and trained 50,000 men in 10,000 buildings and on 170,000 acres of land.19 After Maddox completed his training at Camp Blanding, he joined the 10th Infantry Regiment of the 5th Infantry Division.20

The 5th ID fought in World War I and proved pivotal in the US Army’s contribution to end the war in 1918. During World War II, General S. Patton’s Third Army commanded the 5th ID. Given the nickname “The Red Diamond Men” for the division’s red diamond insignia, the men of the 5th ID trained in Iceland and then England to prepare for their service in France.21 Landing on Utah beach in July 1944, the 5th ID served as replacement troops for those lost during the initial Normandy invasion in June. By July 10, they established a command post at Montebourg, twelve miles north and west from Utah beach on the Cotentin Peninsula. Then they marched south towards Balleroy, a village located twenty miles west of Caen. Throughout the remainder of July, the 5th ID fought at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula, establishing a command post at Cerisy-la Salle by August 4.22 During this time, an artillery shell hit John Maddox, wounding his leg; fortunately, he recovered from this serious injury.23 From Cerisy-la Salle, Maddox’s 10th Infantry Regiment left Normandy and marched 125 miles south to Angers, encountering light resistance en route from disorganized German units. Angers proved geographically and tactically significant, as the city marked a central path to exit the Brittany region towards central and eastern France.24

On August 8, 1944, Louis Bordier, a leader in the French resistance, directed the American troops to Prunier, south of Angers, where the railroad bridge over the Maine River–le Petit Anjou–remained intact. The German soldiers risked everything to prevent the capture of this crucial bridge, even suicidal tactics. Despite their efforts to thwart the Allies, the 11th Infantry Regiment of the 5th ID secured the bridgehead. Before the end of the day, Maddox’s 10th Infantry Regiment crossed the bridge to participate in the attack of Angers from the city’s southwest, confronting fierce enemy resistance. Under suffocatingly hot weather, the regiments of the 5th ID advanced into Angers, where they faced urban combat; they fought Germans behind every house and wall. After two days of intense warfare and mopping-up operations, the 5th ID finally liberated the city on August 10, marking the largest French city that the Allies had liberated since D-day.25 The battle for Angers also signified a crucial victory for the 5th ID, as it enabled further advances eastward into France.26

After the battle for Angers, Maddox’s 10th Infantry Regiment advanced 120 miles northeast to the suburbs south of the medieval city of Chartres, in the small town of Nicorbin, only fifty miles from Paris. On August 19, the 10th Infantry Regiment strengthened its position and completed mop-up operations while the rest of the 5th ID secured Chartres and presented a captured German limousine to General Patton as a clear sign of their victory. Three days later, on August 22, the 10th Infantry Regiment seized Malesherbes, capturing an intact bridge over the Essonne River. The 5th ID’s engineer units and pontoon companies laid out several treadway bridges during these specific advancements, demonstrating their tactical centrality as such constructions enabled troops and armored units to cross over the increasing number of streams and rivers en route toward central and eastern France.27

On August 25, as the Allies liberated Paris, the 10th Infantry Regiment received the order to cross the Seine River at Montereau-Fault-Yonne, nearly fifty miles southeast of the capital city. In two and a half hours and covered by smoke from 81mm mortars, the 10th Infantry Regiment completed this order using assault boats. Then, to liberate Montereau, Maddox’s Regiment paid a heavy tribute, losing sixty-two enlisted men and one officer. The 5th ID commander awarded the 10th Infantry Regiment a unit citation for this action, and Patton gave them a Letter of Commendation. After the war, the unit historian, David Polk, noted:

The way was opened for the Allied Armies to cut Paris off from the south, and to continue encirclement of the city, and its suburbs by driving north from the Fifth Division’s Seine River bridgehead. 28

With Angers, Chartres, and the south of Paris under Allied control, the 5th Division moved further into the east of France, where it faced more infrastructure ruin, including destroyed bridges, blocked roads, and stiff German resistance on the road to Metz. The 5th ID seized Rheims, despite German entrenchment, on August 29. The Division moved to Verdun and, by August 31, established a bridgehead across the Meuse River. At that point, their march forward halted as a result of logistics failures. With the Allies moving so quickly across 150 miles of France, the supply lines could not keep up; they ran out of gas, literally.29

Despite the continued difficulty regarding gasoline shortages in September 1944, the 5th ID arrived near Metz. Maddox’s 10th Infantry Regiment fought in the southwest area of Metz, around the villages of Arnaville, Corny, Arry, and Lorry-Mardigny. The 10th Infantry Regiment encountered violent combat, with German forces using tanks and ample artillery pieces, demonstrating stubborn and fanatical resistance. Such violence made the crossing of the Moselle River incredibly difficult on September 10. After five days of agonizing combat conditions, the 10th Infantry Regiment secured the bridgehead on the east side of the Moselle River, but at the cost of exceptionally high casualties. Probably during the fierce combat to secure the bridge on the Moselle River, an artillery shell fragment hit John Maddox in his thorax and abdomen. Sergeant John Maddox succumbed to his wounds on September 17, 1944, joining the 926 men on the 10th Infantry Regiment’s casualty list for September 17-23, 1944.30

Legacy

After Maddox’s death, the 5th ID continued attacking Metz, liberating the fortified city on December 13, 1944, enabling access to the Saar River. The initial plan changed, however, when the Germans launched their final offensive with the Battle of the Bulge on December 16, 1944. The 5th Division rushed into the southern part of the bulge, protecting Luxembourg City. When they crossed the Sauer River at the end of January 1945, they entered Germany and breached the Siegfried Line. On March 22, they reached the Rhine River at Oppenheim and took Frankfurt a few days later. In April 1945, the Division participated in reducing the Ruhr Pocket, an operation that trapped three German divisions and led to the capture of over 300,000 German soldiers. At the end of April, the 5th ID moved 300 miles away where the borders of Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia joined to finally end the war in Czechoslovakia, fighting against a Panzer Division.31

Several memorials stand for the 5th ID along their liberating path. The Prunier railway bridge outside of Angers remains dedicated to the Division for liberating the town.32 Currently, the Society of the Fifth Division catalogs and commemorates the members of the 5th ID through reunion events and the publication of The Red Diamond, a quarterly newsletter.33

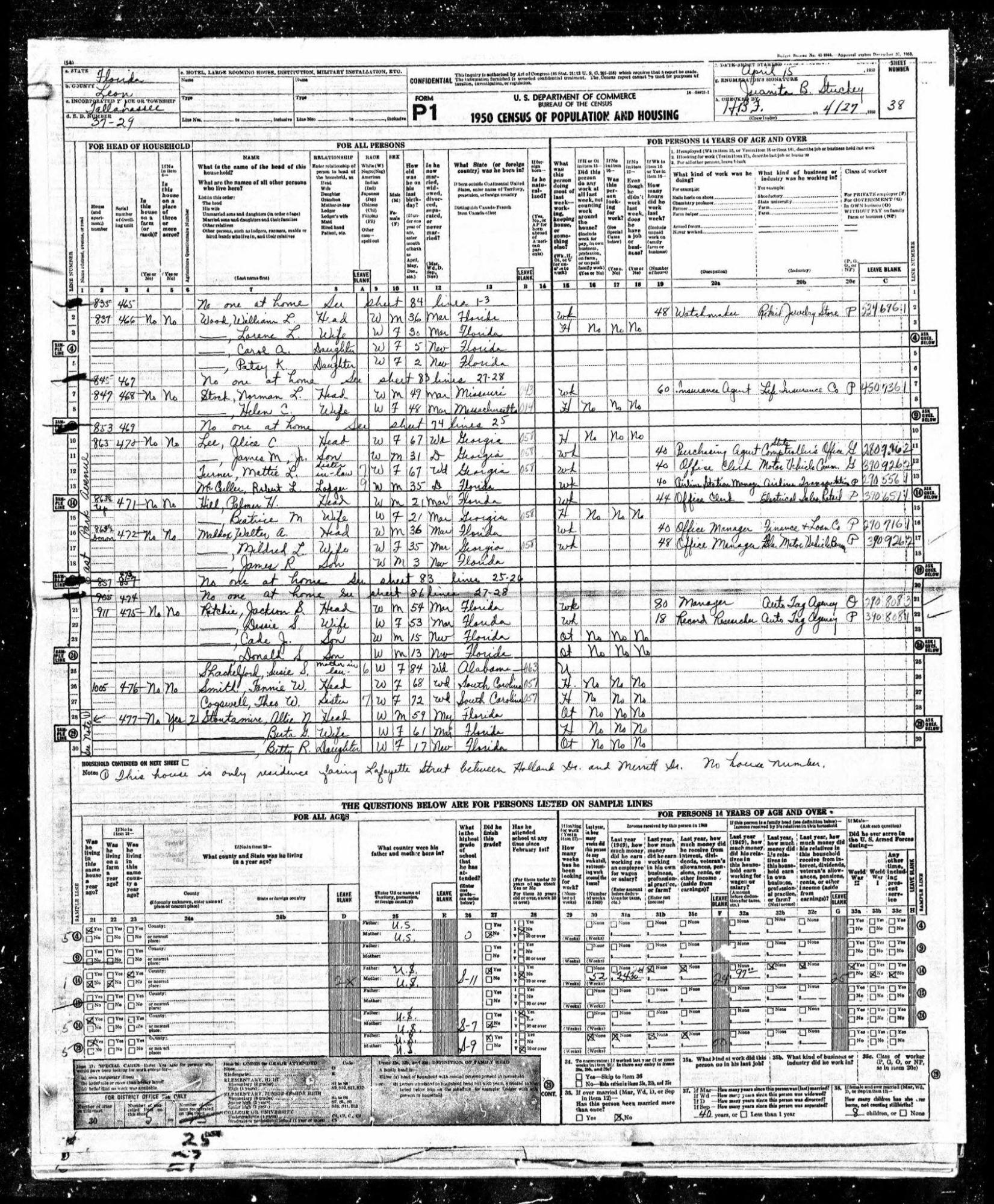

Back home and during the same month of John’s death, Helen finalized a divorce.34 John left behind his parents and brother. Walter Jr. was deployed to the 56th Field Artillery Brigade as part of the Florida State Guard.35 After the war, he settled in Tallahassee, FL, with his wife, Mildred Maddox.36 Walter Jr. continued to remember his brother several years after his death, as on February 22, 1947, Walter Jr. and Mildred welcomed their son, James Robert Maddox. Likely in remembrance of his brother, Walter Jr. gave his son John’s middle name, seen on the 1950 US Federal Census here, as a way to memorialize his younger brother in the next generation of the Maddox family.37 Three years after John’s death, Walter Sr. passed away in 1947. John’s mother lived until 1972 and remains buried alongside her husband in a companion plot of the Friendship Methodist Cemetery in Zolfo Springs, FL.38 Walter Jr. lived until the age of 81, passing away in 1996.39

John Maddox was posthumously awarded a Purple Heart for his sacrifice during World War II. He rests in the Lorraine American Cemetery in France, along with other brave soldiers from World War II who fought until their last breath to liberate the European continent.40

1 “U.S. WWII Draft Registration Cards,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 12, 2023), entry for John Robert Maddox, service number 34545189 ; “1930 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 12, 2023), entry for Walter, Lucile, Walter Jr, and John Maddox, Avon Park, Highlands, Florida.

2 “U.S. WWII Draft Registration Cards,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 12, 2023), entry for Walter Alexander Maddox, serial number 20422525; “1930 U.S. Census.”

3 “Walter L Maddox,” FindAGrave, accessed September 17, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49974423/walter_l-maddox/; “1900 United States Frederal Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed December 4, 2022), entry for Walter L. Maddox, Crewsville, Desoto, Florida.

4 “U.S., WWI Draft Registration Cards,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed September 3, 2024) entry for Walter Letcher Maddox. Interestingly, Walter’s World War I draft registration card misspells his middle name. During World War I, clerks were mainly responsible for filling out draft registration cards, and it is likely that the clerk here misheard or did not know how to spell “Letcher.”At the bottom of the form, which required draftees themselves to sign, Walter correctly spelled “Letcher.” The difference in calligraphy between the two “Letchers” further points to the clerk misspelling Letcher and Walter correctly writing his own middle name. Moreover, Walter received education as a child (1900 US Census), which would likely prevent him from misspelling his own middle name. Although minor, Walter’s World War I draft registration card broadly illuminates the complex issues historians encounter when engaging with primary sources. This example demystifies the apparent transparency from records in the past, instead emphasizing the mistakes and even prejudices that records can contain and unveil.

5 “Lucile S Maddox,” FindAGrave, accessed December 4, 2022, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi; “1900 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed December 4, 2022), entry for Helen L Skipper, Zolfo, Desoto, Florida.

6 “1930 U.S. Census,” entry for Walter L. and John R. Maddox, Avon Park, Highlands, Florida;

7 “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 12, 2023), entry for Walter, Lucille, Walter Jr., and John R. Maddox, Wauchula, Hardee County, Florida. The 1940 census asked residents to list their place of residence in 1935, which the Maddoxs’ listed as Polk County.

8 William B. Stronge, The Sunshine Economy: An Economic History of Florida Since the Civil War (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2008), 130.

9 Gene Smiley, “Recent Unemployment Rate Estimates for the 1920s and 1930s,” The Journal of Economic History 43, no. 2 (1983): 488.

10 Stronge, The Sunshine Economy, 129.

11 Stronge, The Sunshine Economy, 140-141.

12 “U.S. WWII Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 5, 2025), entry for John R. Maddox; “Miss Helen Roberts, Sebring, Is Bride of Robert Maddox,” The Tampa Tribune (Tampa, Florida), October 25, 1942, Newspapers.com (www.newspapers.com: accessed March 5, 2024); “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry; The 1940 US Federal Census listed that John Maddox completed three years of high school by April 11, 1940, meaning he likely completed his four years of high school education in 1941.

13 “U.S. WWII Draft Registration Cards,” entry for John R. Maddox; “Hendricks Field History,” Sebring Multimodal Logistics Center, accessed April 12, 2023, https://sebring-airport.com/hendricks-field/.

14 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed October 7, 2024), entry for John Robert Maddox.

15 “U.S. WWII Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Fold3 (www.fold3.com: accessed April 12, 2023), entry for Walter A. Maddox, serial number 20422525; “U.S. WWII Draft Registration Cards,” entry for Walter A. Maddox.

16 “Florida, Marriage Records, 1927-2001,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed November 1, 2022), entry for John R. Maddox and Helen Roberts; “Miss Helen Roberts, Sebring, Is Bride Of Robert Maddox,” The Tampa Tribune (Tampa, Florida), October 25, 1942, Newspapers.com (www.newspapers.com: accessed September 3, 2024).

17 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” entry for John R. Maddox, service number 34545189.

18 “U.S. WWII Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” entry for Walter A. Maddox; “U.S. WWII Draft Registration Cards,” entry for Walter A. Maddox.

19 George E. Cressman, “Camp Blanding in World War II: The Early Years,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 97, no. 1 (2018): 36.

20 “Headstone Inscription and Interment Records,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 13, 2023), entry for John R. Maddox, St. Avold Cemetery, France.

21 “5th Infantry Division,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed April 13, 2023, https://history.army.mil/documents/eto-ob/5id-eto.htm; “The Fifth Infantry Division, World War II,” Society of the Fifth Division, accessed April 13, 2023, http://www.societyofthefifthdivision.com/WWII/WW-II.htm.

22 “5th Infantry Division,” U.S. Army Center of Military History.

23 “U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 13, 2023), entry for John R. Maddox, July 1944.

24 “After Action Report for September, 1944,” database, Fold3 (www.fold3.com: accessed April 13, 2023), 10th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division.

25 “After Action Report for September, 1944,” 10th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division.

26 “After Action Report for September, 1944,” 10th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division; Sylvain Bertoldi, “Août 1944. Angers est libérée: Chronique Historique,” Vivre à Anger, no. 178, September 1994, Archives Municipales. Accessed October 18, 2024. https://archives.angers.fr/chroniques-historiques/les-chroniques-par-annees/1989-1995/aout-1944-angers-est-liberee/index.html; David Polk, Fifth Infantry Division: World War I, World War II, Vietnam & Panama (Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 1994), Internet Archive, 37-38, https://archive.org/details/fifthinfantrydiv00polk.

27 Polk, Fifth Infantry Division, 38-42; “After Action Report for September, 1944,” 10th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division.

28 Polk, Fifth Infantry Division, 41-44; “After Action Report for September, 1944,” 10th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division.

29 Polk, Fifth Infrantry Division, 43-44.

30 “U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” entry for John R. Maddox, September, 1944; “Headstone Inscription and Interment Record,” entry for John R. Maddox; Polk, Fifth Infantry Division, 43-45; “After Action Report for September, 1944,” 10th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division; The 926 total accounts for enlisted men who were killed, missing, wounded, and injuried. From the 926 total, 38 enlisted men died (which includes Maddox), 250 were missing, 430 were wounded, and 211 were sick or injured.

31 “The Fifth Infantry Division, World War II,” Society of the Fifth Division.

32 “Memorial liberation d’Angers – Prunier, France,” Waymarking.com, accessed April 13, 2023, https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMWMHR_Memorial_liberation_dAngers_Prunier_France

33 Society of the Fifth Division, United States Army, accessed April 13, 2023, http://www.societyofthefifthdivision.com/.

34 “Florida Divorce Records, 1927-2001,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 13, 2023), entry for John Robert Maddox and Helen, Highlands, Florida, 1944.

35 “U.S., Adjutant General Military Records, 1631-1976,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 13, 2023), entry for Pvt. Walter A. Maddox, 56th Field Artillery Brigade, Jacksonville, Florida. The US government federalized the National Guard during America’s entry into World War II, resulting in the Florida State Guard in which Walter Jr. served.

36 “1950 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 13, 2023), entry for Walter A. Maddox, Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida.

37 “New Arrivals,” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, Florida), February 23, 1947, Newspapers.com (www.newspapers.com: accessed September 17, 2024); “1950 U.S. Census,” entry for James Robert Maddox, Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida.

38 “Lucile S. Skipper Maddox,” FindAGrave, accessed April 13, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49974434/lucile-s-maddox.

39 “Walter Alexander Maddox,” FindAGrave, accessed April 13, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/83698465/walter-maddox.

40 “Headstone Inscription and Interment Record,” entry for John R. Maddox.