Pvt. James “Bobby” R. Maddox (1924 – October 9, 1944)

15th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division

by Sam Dettman and Allison Stanley

Early Life

James Robert “Bobby” Maddox was born March 25, 1924, in Detroit, MI, to Nita and Claude H. Maddox Sr.1 Claude came from a family that had lived in Kentucky for at least two generations.2 Nita was born in Alabama in 1900.3 At some point before 1918, Claude moved to Munson, FL where he worked for the Bogdad Land and Labor Company caring for livestock and doing other agricultural work.4 At the age of twenty three, during World War I, Claude joined the Navy. He served as a hospital apprentice and a pharmacist’s mate at the Naval Training Station in Newport, RI, between April 1918 and October 1919.5 Nita’s family moved to Pensacola, FL before 1920.6

Claude and Nita married on September 25, 1922, in Detroit, MI. They may have met in Florida, and Nita joined Claude who had secured work in the automobile industry headquartered in Detroit.7 Before Bobby’s brother William, “Billy,” came along in 1925, the family moved again, as Billy was born in Florida. Shortly after his birth, the family moved again to Savannah, GA where Claude took a job as a sales manager for the Dixie Chevrolet Sales Company.8 Within a few years, Claude probably received a transfer within the Chevrolet motor company, as they had moved to Columbia, SC. The Maddox’s welcomed their third son, Claude Jr., in South Carolina in 1933, at the height of the Great Depression.9

The Maddox family, pictured here in the early 1940s, moved back to Pensacola, FL, by 1935, and finally settled in Tallahassee, FL, in 1940.10 Having weathered the Great Depression, the family rented their home and lived on Claude Sr.’s annual income of $2,500.11 All three boys attended school. The oldest boys attended Leon High School, playing basketball and football.12 In 1942, their basketball team made it to the state championship against the Miami Stingarees.13 Bobby dated Betty Bryson, pictured here in their football and cheerleading uniforms.14

Graduating early in January 1943, Bobby Maddox gave one of four speeches at the commencement ceremony focused on the “development of the four-square life.” As the star athlete, he elaborated on the “physical phase,” stating, “Health is the foundation for individual success. Health is one of the greatest assets that industry looks for, and health is the foundation of our nation’s victory in this war.”15 Just one month later, at the age of eighteen, Bobby joined the US Army.16 His brother Billy graduated a year later and followed in his brother’s footsteps, joining the Army at Camp Blanding in the summer of 1944.17

Military Service

Private Bobby Maddox began his service in the US Army on February 27, 1943, at Camp Blanding, FL.18 One month later, his mother, Nita, passed away.19 By June, he transferred to Camp Wolters, TX to receive more training in the Army’s replacement unit program.20 The Army assigned him to the 3rd Infantry Division, 15th Infantry Regiment.21 The 3rd Infantry Division served with honor in France during World War I, earning the nickname the Rock of the Marne and taking the motto “Nous resterons la!” often translated as “We are staying put!”22

As Bobby enlisted in February and continued training in June, he likely joined the 3rd Infantry Division during “Operation Husky,” the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943.23 Sicily held strategic importance for the Axis Powers because an invasion would give the Allies a foothold in Europe. As a result, the Italians and Germans defended its ports fiercely. The Allies used Tunisia, captured as part of Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa in 1942 and 1943, as a base to attack Italy. The 1st and 3rd Infantry Divisions’ amphibious landing entered on beaches near Licata, a city on the south-central coast of the island, on July 10, 1943. The Allies tasked the 1st and 3rd American Infantry Divisions with clearing out beaches and capturing the port and airfields. Once beached, the 3rd Division entered intense combat. Within two days, the Allies captured Licata and Syracuse, earning them a seventy-mile stretch along the southern coast of Sicily and providing port access. On July 16, the 3rd Division traveled about thirty miles northwest to Argrigento, encountering heavy reinforcement from the enemy. It nevertheless captured the city the following day and secured another new port.24

A new plan to capture Palermo, Sicily’s capital located on the northern coast seventy-five miles away, required Bobby’s 3rd Division to move quickly. In capturing Palermo, the Allies split the Italians and the Germans between the western and eastern sides of the island. The 3rd Division began its 100-mile trek alongside the 2nd Armored Division and 82nd Airborne Division, all part of the Seventh Army. When the men arrived in Palermo on July 22, the 3rd Division entered the city while the 2nd Armored Division cleared Axis forces out of the rest of western Sicily. The 7th Infantry Regiment entered first with the 3rd Division’s 15th Infantry Regiment following closely behind, capturing thousands of enemy soldiers. Within 72-hours of the Allies’ arrival, the city surrendered and the 3rd Infantry Division occupied and patrolled the city for several days. Around the same time, on July 25, 1943, the Italians voted their leader, Benito Mussolini, out of power. Within a few months, the new Italian government declared war on Germany and joined the Allies.25

After a few days of rest, the 3rd Division moved to relieve the 45th Division in San Stefano di Camastra, Sicily, on July 31, traveling ninety miles northeast in seventeen days. The division engaged in combat on August 2, 1943. The Germans held the advantage, but Bobby’s 15th Regiment successfully moved on the following day toward the Furiano River. The rough terrain and heavy combat made it difficult for the 3rd Division to advance. As the 15th and 30th Infantry Regiments closed in on Messina, the city formally surrendered on August 17, and enemy troops evacuated Sicily, leaving the territory to the Allies.26

Following the capture of Sicily, Allied forces turned their attention to Salerno because it provided access to mainland Italy with relatively few defenses. The US Fifth Army arrived on the beaches following the Navy’s sweep of the Gulf of Salerno on September 9, 1943.27 As part of the larger Allied effort, the 3rd Division, dispatched from Sicily, captured fleeing Germans in the small town East of Salerno. The retreating Germans destroyed the bridges to cross the Volturno River, forcing the 3rd Division to improvise by using Navy life rafts with gas tins and water cans as flotation devices.28

After most of the division successfully crossed the Volturno River on October 14, 1943, about forty-five miles inland from the coastal city of Naples, the 3rd Division advanced northwest towards Dragoni. Enemy troops blocked the 15th Regiment in Roccaromana, but it managed to break through on October 22. Thanks to the 15th Regiment’s foothold on Mount della Costa overlooking a supply route, Bobby and his comrades forced the Germans out and allowed the 3rd Division to continue its advance into mainland Italy. By early November, the 3rd Division had moved across the peninsula, facing continuous combat in the hills, working to reach Germany’s defensive positions at the Gustav Line.29

In mid-November 1943, the 36th Infantry Division relieved the 3rd Division from combat for a period of rest. Unfortunately, just days before, Bobby Maddox was wounded in action and sent to a hospital in North Africa to recover.30

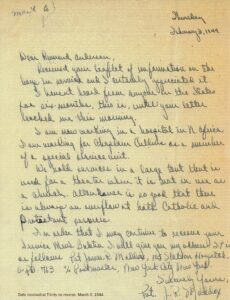

While there, doctors also treated him for cholangitis, an “inflammation of the bile duct system…. [usually] caused by a bacterial infection.”31 While on extended leave, Bobby assisted the hospital chaplain. In one of his letters, pictured here, to his pastor, Dr. Jack Anderson of Trinity United Methodist Church, in Tallahassee, he explained:

I am now working in a hospital in N. Africa. I am working for Chaplain Cullius as a member of a special service unit. We hold services in a large tent that is used for a theater when it is not in use as a church. Attendance is so good that there is always an overflow at both Catholic and Protestant services.32

The hospital in North Africa discharged Bobby in February 1944.33 Stationed in Anzio with light duty, he worked with a special unit providing clean clothes and showers to the fighting men, boosting morale for those he encountered. Despite no longer working alongside the chaplain, he maintained his faith through it all. Bobby discussed his faith and experience with Dr. Anderson. In another letter, he told his pastor that, “Church Service this morning was held on the beach within sight and hearing of the artillery shells of the enemy.” He closed by offering a prayer “that the war will soon end and we may return to our homes, families, and friends.” 34

A few weeks after Operation Dragoon, the massive amphibious landing in southern France, which began on August 15, Bobby rejoined his unit, which had landed on the beaches of the French Riviera on the first day alongside other divisions in the Seventh Army. 35 Once Bobby returned, his regiment had already traveled over 400 miles northeast into Lorraine, making their way closer to the German border. By September 15, the men pushed across the Moselle and Meurthe Rivers heading into the Vosges region. The heavy forest, mountain peaks and valleys, and narrow roadways made moving through the Vosges difficult. On September 26, Bobby and the rest of the 15th Infantry Regiment entered an exhausting battle. The Germans, holding the high ground on the mountain ridge, organized numerous roadblocks near St. Amé, next to the town of Remiremont, and prevented the Allies from advancing. Over the next four days, the 15th Regiment fought on its own until the 7th Infantry Regiment, also of the 3rd Division, arrived on September 30. The Allies could not move into Remiremont and capture the nearby quarry in Cleurie, which provided much needed cover, without routing the Germans from the ridge. Only once the 3rd Division’s 30th Infantry Regiment joined the fight on October 1, did the Allies begin making progress– triangulating the German position. It took the entire 3rd Division a week to take the German soldiers’ high ground.36 On October 9, 1944 the 15th Regiment fell under heavy combat when Lt. Victor Kandle led a platoon of sixteen soldiers to attack a German position. Private Robert “Bobby” Maddox was likely among those killed in the deadly fight just southeast of Epinal, one day before the Americans secured the quarry on October 10.37 He was only twenty years old.

Legacy

At the end of 1944, the 3rd Division fought in the Colmar Pocket, a fierce battle lasting nearly two months around the Alsatian city. The division continued northeast, eventually reaching Germany in March 1945.38

Killed in action in the European theater, Bobby Maddox earned a Purple Heart.39 Lt. Kandle also lost his life in December 1944; he earned a Purple Heart, a Silver Star, and a Medal of Honor. He is buried near Bobby in Epinal American Cemetery.40 Two of 1,633 men of the 15th Regiment of the 3rd Infantry Division killed in action.41 The 3rd Division’s sacrifice during World War II is memorialized in St. Mark’s Chapel, on a US-Italian military base in Italy, through stained glass windows which commemorate all the units that served in the Italian Campaign; a rock commemorates the liberation of Montecorvina Rovella, a small town near Salerno, Italy; and a marker, as seen on the picture, identify the Cleurie Quarry near Epinal, France, the area where Bobby passed.42

Bobby was survived by his father, Claude and his younger brother Claude Jr. He also left behind his high school sweetheart, Betty Bryson, whom he planned on marrying when he returned home from the war.43 His brother Billy tragically died on October 10, 1944, one day after Bobby’s death. Billy spent a few days leave visiting friends in Tallahassee, just before shipping out. On the way back from Camp Blanding, with a friend, they stopped to change a tire, and Billy was struck by a passing motorist, never regaining consciousness.44

Billy, who served in the Army like his older brother, never got the chance to serve overseas. In the chaos of the war years, Billy never received a headstone. Thanks to the work of David Wilson, a former football coach for Lincoln High School, and Gordon Lightfoot, both members of the Tallahassee Amvets Post 1776, and Claude Jr.’s children, Sarah Farren and Claude Maddox III, Billy received a civilian headstone in 2022.45 Then, on Memorial Day 2023, Billy received the National Cemetery Administration headstone, pictured here, that he earned in 1944–nearly eighty years after his death.46

While the brothers are buried nearly 5,000 miles apart, they remain connected in death as they did in life. Bobby rests in the Epinal American Cemetery in eastern France, just thirteen miles from where he fell.47 The family continues working on inducting Bobby into the Leon High School Hall of Fame, hopefully in 2023, following Billy’s induction in 2022.48

1 “U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 7, 2023), entry for James Maddox, serial number 593; “1930 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 7, 2023), entry for Bobbie Maddox, Columbia, Richland County, South Carolina.

2 “1910 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 7, 2023), entry for Claude Maddox.

3 “1920 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 7, 2023), entry for Nita Lowe, Pensacola, Escambia County, Florida.

4 “U.S., WWI Draft Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 8, 2023), entry for Claude Maddox, serial number 117.

5 “World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed September 20, 2016), entry for Claude Maddox, serial number 117; “World War I Service Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 10, 2023), entry for Claude Maddox.

6 “1920 U.S. Census,” entry for Nita Lowe.

7 “Michigan, Marriage Records, 1867-1952,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 7, 2023), entry for Claude Maddox.

8 “Georgia, City Directories, 1822-1995,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 7, 2023), entry for Claude Maddox.

9“1930 U.S. Census,” entry for Bobbie Maddox; “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 7, 2023), entry for Claude Maddox Jr., Tallahassee, Leon County, Florida.

10 “1940 U.S. Census,” entry for Bobbie Maddox; Family photograph, c.1940. We would like to thank Sarah Farren and Claude Maddox III, Bobby’s niece and nephew, for allowing us to publish family photos.

11 “1930 U.S. Census,” entry for Claude Maddox.

12 “Bobby Maddox Dies in Action,” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, FL), October 30, 1944, Newspapers.com.

13 “Miami Plays Leon in Finals of High School Cage Meet,” The Tampa Bay Times (Tampa, FL), March 14, 1942, Newspapers.com.

14 Bobby Maddox and Betty Bryson, c. 1942. We are grateful to Sarah Farren and Claude Maddox III for allowing us to publish the family photos.

15 “Four-Square Life Emphasized by Leon High School Seniors,” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, FL), January 31, 1943, Newspapers.com; “Students to Make Own Talks at Leon Graduation Friday,” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, FL), January 28, 1943, Newspapers.com.

16 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed February 9, 2023), entry for James Maddox, service number 34546465.

17 “U.S., WWII Hospital Admission Card Files,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 8, 2023), entry for William Maddox, service number 34934367.

18 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” entry for James Maddox.

19 “Nita P Lowe Maddox,” Find a Grave, accessed February 9, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/107461147/nita-p-maddox.

20 “Camp Wolters,” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, FL), June 4, 1943, Newspapers.com.

21 “U.S., World War I, World War II, and Korean War Casualty Listings,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 19, 2016), entry for James Maddox.

22 Philip A. St. John, History of the Third Infantry Division (Paducah: Turner Publishing Company, 1994): 7.

23 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” entry for James Maddox.

24 Matthew G. St. Clair, “Operation Husky and the Invasion of Sicily,” in The Twelfth US Air Force: Tactical and Operational Innovations in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, 1943–1944, (Alabama: Air University Press, 2007), 17-29; Donald G. Taggart, History of the Third Infantry Division in World War II (Washington: Infantry Journal Press, 1947), 52-57.

25 Taggart, History of the Third Infantry Division in World War II, 52-63; Andrew J. Birtle, Sicily: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1993), 14-16.

26 Taggart, History of the Third Infantry, 63-74.

27 “The U.S. Navy and the Landings at Salerno, Italy, 3–17 September 1943,” Naval History and Heritage Command, May 10, 2019, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1943/salerno-landings/landings-at-salerno-italy.html.

28 Taggart, History of the Third Infantry, 80-88.

29 Taggart, History of the Third Infantry, 88-96.

30 “Bobby Maddox Dies in Action,” Tallahassee Democrat.

31 “U.S., WWII Hospital Admission Card Files,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 7, 2023), entry for James Maddox, service number 34546465; “Cholangitis,” Johns Hopkins Medicine, (https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/cholangitis, accessed February 8, 2023); “Bobby Maddox Dies in Action,” Tallahassee Democrat. Quotation from the Johns Hopkins’ medical information site. According to the newspaper article cited here, Maddox was wounded in action. The hospital record from the same period indicates “disease,” specifically “cholangitis.” We do not know if the cholangitis resulted from an injury, an illness he contracted while living in combat conditions, or something he contracted while in the hospital while being treated for other injuries.

32 “Our Men in Service,” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, FL), March 5, 1944, Newspapers.com; Letter from James Maddox to Rev. Anderson, Thursday, February 3, 1944. Trinity United Methodist Church, Committee for the Preservation of Church History, Tallahassee, FL provided us with special permission to publish the letters. Our thanks to the Trinity Methodist Church for allowing us to include Bobby’s letters.

33 “U.S., WWII Hospital Admission Card Files,” entry for James Maddox. “Bobby Maddox Dies in Action,” Tallahassee Democrat.

34 Letter from James Maddox to Rev. Anderson, May 14, 1944. Provided for use by special permissions from Trinity United Methodist Church, Committee for the Preservation of Church History, Tallahassee, Florida. The entire collection of WWII correspondence from Rev. Anderson is available at https://www.tumct.org/wwii-letters/

35 Duane C. Denfeld, “15th Regiments, United States Army,” historylink.org (http://www.historylink.org/File/10353: accessed September 21, 2016); “France’s Second D-Day: Operation Dragoon and the Invasion of Southern France,” American Battle Monuments Commission, (https://www.abmc.gov/news-events/news/france%E2%80%99s-second-d-day-operation-dragoon-and-invasion-southern-france, accessed August 15, 2014).

36 Taggart, History of the Third Infantry, 237-250; Jeffery J. Clarke and Robert Ross Smith, Riviera to the Rhine (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 1993), 248-251.

37 Duane C. Denfeld, e-mail message to Allison Stanley, October 3, 2016.

38 Taggart, History of the Third Infantry, 283-320; “3d Infantry Division,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed May 19, 2023, https://history.army.mil/documents/eto-ob/3id-eto.htm.

39 He also earned the European African Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with a bronze service star, a Good Conduct Medal, and an Expert Infantry Badge. Extracts from the National Archives and Records Administration file on James Maddox, provided by his niece, Sarah Farren.

40 “Victor L. Kandle,” American Battle Monuments Commission, (https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/kandle=victory, accessed May 27, 2023).

41 Duane C. Denfeld, “15th Regiments, United States Army,” historylink.org (http://www.historylink.org/File/10353: accessed September 21, 2016).

42 “Cleurie Valley Liberators,” American War Memorials Overseas, accessed March 27, 2023, https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=402&MemID=657; “3rd Infantry Division Liberation Rock,” American War Memorials Overseas, accessed April 11, 2023, https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=1976&MemID=2608; “St. Mark’s Chapel,” American War Memorials Overseas, accessed April 11, 2023, https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=1352&MemID=1769.

43 Sarah Farren email to Amelia Lyons and Sam Dettman, February 10, 2023.

44 “Billy Maddox Dies at Camp From Injuries,” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, FL), October 10, 1944, Newspapers.com; “For 78 years, Billy Maddox was in an unmarked grave. Now this former Leon star, veteran gets overdue honors,” Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, FL), September 12, 2022.

45 “Veteran gets overdue honors,” Tallahassee Democrat.

46 We would like to thank the VA’s National Cemetery Administration for its assistance in processing the family’s request for a military headstone.

47 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 7, 2023), entry for James Maddox, service number 34546465.

48 Sarah Farren email to Amelia Lyons and Sam Dettman, February 10, 2023, Orlando, Florida; “Veteran gets overdue honors,” Tallahassee Democrat.