PFC Sherman Knights (February 12, 1924 – January 27, 1946)

2794th Engineer Firefighting Platoon

by Alexis Sutton and Elizabeth Klements

Early Life

Sherman Knights was born on February 12, 1924, to Ethel Evans and Eugene Knights in Miami, FL.1 Not much is known about his parents. Ethel was born in the Bahamas and likely immigrated to Miami as a young adult, since she does not appear in earlier US census records.2 In Miami, she met and married Eugene Knights, and had Helen (1922), Sherman (1924), and Eugenia (1926).3 At some point in 1926 or early 1927, Eugene died, leaving Ethel a widow.4 After 1930, Eugene’s widowed mother, Catherine Turner, raised the three children alone in Miami.5 Ethel may have also died, or she may have returned to the Bahamas to support her children and her mother-in-law from a distance. Segregation in the Jim Crow south limited the type of work available to African Americans and black immigrants, and Helen may have found better employment opportunities elsewhere. This is all the more likely because Catherine Turner was not employed while the children grew up, suggesting that the family had some other source of financial support.6

Sherman and his siblings grew up in a Bahamian community in Overtown, a historically Afro-Caribbean neighborhood in the heart of Miami. Due to the discriminatory city planning practices, it, and the other segregated neighborhoods in Miami, was overcrowded, with unsafe housing and only partial access to municipal facilities like water and power. Despite this, black entrepreneurs turned Overtown into a center of arts and culture: this “Harlem of the South,” as it was known, hosted famous black artists, intellectuals, and entertainers in the first half of the twentieth century.7 Miami’s white leaders, however, disliked this prominent black presence in downtown Miami and in the mid-1930s began to move Overtown residents outside city limits in order to expand white businesses into the area. With New Deal funding, the city built Liberty Square on the city’s outskirts, the first public housing project specifically for African Americans in the entire country.8 It opened up in 1937, and it was around this time that Catherine Turner moved her grandchildren to a rental house in the neighborhood of Liberty City, very close to the Liberty Square housing project.9

All three children received a grammar-school education, which was common for African Americans in Jim Crow south whose segregated schools received little state support and funding.10 In 1940, Helen, the oldest daughter, did housework at a private residence, and Sherman, aged sixteen, was unemployed. Sometime between 1940 and 1942, Sherman was arrested on unknown charges and ended up in the Tavares Prison Camp 48 in Tampa, FL.11 Florida’s Black Codes intended to penalize, even terrorize, African Americans. The white justice system handed out harsh punishments to African Americans for petty crimes including “vagrancy” – that is, being unemployed. Sherman most likely fell victim to Florida’s vagrancy code and was forced to work on a chain gang to pay the resulting fines.12

Military Service

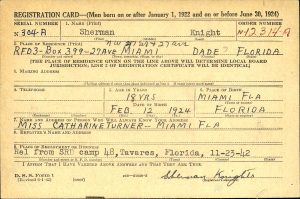

On November 23, 1942, Sherman was released from Tavares Prison Camp 48 and, having recently turned eighteen, filled out his draft card, seen here, at the prison camp on the day of his departure.13 Four months later, the US Army called him to service, and Sherman entered Camp Blanding, FL, for training on March 23, 1943.14 Although Congress’s 1940 Selective Training and Service Act prohibited discrimination in the armed forces, it still shaped the experiences of African American servicemen throughout the war. The US military leaders preferred to assign black soldiers to service and support roles in the Quartermaster or Engineer units, due to racist fears about training them in armed combat and prejudices about their ability to fight. At the training camps, especially those in Jim Crow south, the camp authorities put the African American enlistees in the most undesirable quarters and assigned them the more menial camp duties, such as cooking, cleaning, and transportation.15

Like many African American soldiers, Sherman entered the Engineer Corps. While most segregated engineer units were responsible for building and repairing infrastructure in war zones, Sherman joined one of its few segregated firefighting units – the 2794th Engineer Firefighting Platoon.16 Platoons like the 2794th had a headquarters section and three firefighting sections, each of which were about twenty-six to twenty-eight men. In segregated platoons, these sections were made up of black soldiers who served under white officers. Each platoon had a class-325 firetruck and three class-1000 water-pumping trailers. The platoons acted as mobile fire stations and their main job was to respond to fire emergencies wherever they were assigned. Their duties also included fire safety and fire prevention.17

The US Army activated the 2794th at Camp Patrick Henry, VA, on April 24, 1944, about a year after Sherman entered basic training. The platoon arrived at the European Theater by the winter of 1944 and participated in the Second Battle of the Ardennes, also known in the US as the Battle of the Bugle, which took place on the French-Belgium border from December 1944 to January 1945.18 During this battle, the firefighters were mainly responsible for putting out fires caused by bombings. The enemy aircrafts targeted ammunition trains and supply depots, and the Army needed several firefighting platoons on hand to prevent disastrous explosions and salvage as much of the supplies as they could.19

After the Battle of the Bulge, the 2794th joined US troops as they fought for control of the Rhine River, which formed part of the Franco-German border.20 The Allied forces took the Rhineland region by March 1945 and began a full-scale invasion of Germany which ended with Germany’s surrender on May 8, 1945. After the war in Europe ended, many American soldiers remained in occupied Germany. They acted as a peacekeeping force and participated in the reconstruction. Germany, like much of Europe, had been destroyed by nearly six years of war. Transportations networks, housing, and industries all suffered under Allied bombing. People did not have adequate shelter, fuel for heating, or enough food to eat.21 The 2794th participated in the reconstruction, in the American Zone of southern Germany.22 They must have attended many fires triggered by the detonation of previously unexploded bombs or cooking fires created by inhabitants of buildings with no working stoves or heating.

African American soldiers like Sherman Knights were in a unique position in post-war Germany. As part of an occupying force, they were in positions of respect and power over the local populations, but their own military treated them as second-class citizens. The military police disproportionately targeted black soldiers and the German women who associated with them for infractions that they overlooked when committed by other white soldiers and civilians.23 Germany itself had a mixed response to the presence of African Americans. Germans embraced elements of African American culture, especially jazz, but disliked the relationships between black soldiers and white German women, which they saw as a sign of Germany’s military and moral weakness.24

From this picture of Sherman’s platoon taken on January 21, 1946, a few days before Sherman’s death, we know that the 2794th was stationed in Heidelberg, Germany in early 1946.25 Although the Germans bombed some of the city’s important features, including bridges, just before the Allies arrived, most of the city’s architecture survived the war. As a university town, Heidelberg had not been a target for Allied bombings.26 PFC Sherman Knights, and a fellow platoon member, Tech 5 Earl Spears, both died on January 27, 1946, in a truck accident at the nearby town of Neckargemünd.27

Legacy

PFC Sherman Knights died at the age of twenty-two. His fellow soldiers likely buried him in a temporary cemetery in Germany, but his final resting place is plot K, row 33, grave 32 at the Lorraine American Cemetery in France, an American Battle Monuments Commission cemetery dedicated in 1960.28 Sherman’s wife, Muriel, never remarried. She died in 1967 at the age of forty-one from bronchopneumonia and is buried at the Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery, TX. Her headstone reads: “Wife of PFC Sherman Knights, USA.”29 Sherman also left behind his grandmother Catherine Turner, and his sisters Helen and Eugenia.30 As an African American growing up in the South, segregation shaped Sherman’s life, and he died fighting for a country that did not recognize his equality. The services and sacrifices, however, of Sherman and the rest of the African American soldiers in World War II, helped bring an Allied victory overseas and inspired future Civil Rights victories at home, beginning with the desegregation of the armed forces in 1948.31

1“U.S, World War II Draft Cards,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 10, 2021), entry for Sherman Knight, serial number 304-A. Sherman is referred to as Knights and Knight in different records, but this biography uses Knights because that is the way Sherman signed his name on his draft card. For Sherman’s parents, see his siblings’ Social Security Claims forms: “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed September 27, 2021), entry for Eugenia Knights and Helen Knights.

2 For Ethel’s Bahamian heritage, see “1930 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 10, 2021), entry for Sherman Knights, Miami, Dade County, Florida.

3 “Miami, Florida, City Directory 1925,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed September 27, 2021), entry for Ethel and Eugene Knights, 953 NW 5th Ct; “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007,” entries for Eugenia Knights and Helen Knights.

4 “Miami, Florida, City Directory 1927,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed September 27, 2021), entry for Ethel (wid Eug), 1529 NW 5th Ct.

5 “1930 U.S. Census.” This census year lists Helen as twenty years older and the mother of the other two children, while the 1935 and 1940 censuses list her correct age and identifies her as their older sister. Given the evidence of the 1935 and 1940 censuses, as well as that of Helen’s Social Security Claims Index, the 1930 census taker must have confused Helen’s age and position in the family.

6 “1930 U.S. Census,” entry for Catherine Turner; “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed September 27, 2021), entry for Kathryn Turner, Miami, Dade, Florida.

7 Porsha Dossie, “The Tragic City: Black Rebellion and the Struggle for Freedom in Miami, 1945-1990” (MA diss., University of Central Florida, 2018), 22 – 29; Dorothy Jenkins Fields, “A Look Back at Miami’s African American and Caribbean Heritage,” Miami and Beaches, accessed September 7, 2021, https://www.miamiandbeaches.com/things-to-do/history-and-heritage/miamis-african-american-caribbean.

8 R. Bachin, “Race, Housing, and Displacement in Miami,” University of Miami, accessed September 28, 2021, https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/0d17f3d6e31e419c8fdfbbd557f0edae.

9 “1935 Florida Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed September 28, 2021), entry for Sherman Knight, Miami, Dade, Florida; “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed September 28, 2021), entry for Sherman Knight, Miami, Dade, Florida. Liberty city was also known as Model City.

10 Dionne Danns and Michelle A. Purdy, “Introduction: Historical Perspectives on African American Education, Civil Rights, and Black Power,” The Journal of African American History 100, no. 4 (2015): 576.

11 “U.S, World War II Draft Cards.” This prison camp famously inspired the movie Cool Hand Luke: “Donn Pearce,” Florida Wanderer, https://floridawanderer.wordpress.com/tag/tavares-road-prison/.

12 James A. Schnur, “Caught in the Cross Fire: African Americans and Florida’s System of Labor During World War II,” Sunland Tribune 19, article 8 (1993), https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol19/iss1/8; Jerell H. Schofner, “Custom, Law, and History: The Enduring Influence of Florida’s ‘Black Code,’” The Florida Historical Quarterly 55, no. 3 (Jan. 1977): 277-298.

13 “U.S, World War II Draft Cards.”

14 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October 15, 2021), entry for Sherman Knight, service number 34549332.

15 Jon Evans, “The Origins of Tallahassee’s Racial Disturbance Plan: Segregation, Racial Tensions, and Violence during World War II,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 79, no. 3 (Winter 2001): 349-352.

16 “African-American Engineer Troops,” US Army Corps of Engineers, accessed October 13, 2021, https://www.usace.army.mil/About/History/Historical-Vignettes/Women-Minorities/112-African-American-Engineer/; “U.S., Headstone and Interment Record,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October 15, 2021), entry for Sherman Knights, service number 34549332.

17 Leroy Allen Ward, Army Fire Fighting: A Historical Perspective (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2012), 41, 55, 57 – 78.

18 Ward, Army Fire Fighting, 172; Roger Cirillo, “Ardennes-Alsace,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed October 13, 2021, https://history.army.mil/brochures/ardennes/aral.htm#:~:text=Ardennes-Alsace%2016%20December%201944-25%20January%201945%20In%20his,initiative%20had%20characterized%20Hitler%27s%20influence%20on%20military%20operations.

19 Ward, Army Fire Fighting, 51 – 52.

20 Ward, Army Fire Fighting, 172; Ted Ballard, “Rhineland,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed October 13, 2021, https://history.army.mil/brochures/rhineland/rhineland.htm.

21 Elizabeth Heineman, “The Hour of the Woman: Memories of Germany’s ‘Crisis Years’ and West German National Identity,” The American Historical Review 101, no. 2 (Apr., 1996): 374.

22 Ward, Army Fire Fighting, 172.

23 Alexis Clark, “When Jim Crow Reigned Amid the Rubble of Nazi Germany,” The New York Times Magazine, February 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/19/magazine/blacks-wwii-racism-germany.html; Timothy L. Shroer, Recasting Race after World War II : Germans and African Americans in American-Occupied Germany (Colorado: University of Colorado Press, 2007), 66-70.

24 Shroer, Recasting Race after World War II, 83-85, 149-150.

25 Gene Galanter, “Men of the 2794th Fire-Fighting Platoon in Heidelberg, Germany,” database, The National Archives (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/178140876: accessed October 15, 2021), Photographs of American Military Activities, ca. 1918 – ca. 1981.

26 K. Werrel, “The Strategic Bombing of Germany in World War II: Costs and Accomplishments,” The Journal of American History, 73, no. 3 (Dec., 1986): 704-705.

27 “Sherman Knights,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed March 26,2021, https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/knights%3Dsherman; “Earl E Spears,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed March 26,2021, https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/knights%3Dsherman. For cause of death, see National Archives and Records Administration, Army IDPF, Box 4191, Sherman Knights File. Many thanks to Dr. Amy Giroux for acquiring and sharing Sherman Knights’ NARA records.

28 “Sherman Knights,” American Battle Monuments Commission; “Lorraine American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed March 26, 2021, https://www.abmc.gov/Lorraine.

29 “Texas, U.S. Death Certificates 1903-1982,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com accessed March 11, 2021), entry for Muriel Knights, Texas; “Knights, Muriel J.,” National Cemetery Administration, accessed October 15, 2021, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/ngl/ngl#results-content; “Muriel Johnson Knights,” Find a Grave, accessed October 15, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/3029272/muriel-knights.

30 “Florida 1945 Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 11, 2021), entry for Catherine Turner, Precinct 37, Dade County, Florida; National Archives and Records Administration, Army IDPF, Box 4191, Sherman Knights File.

31 N. Wynn, “The ‘Good War:’ The Second World War and Postwar American Society,” Journal of Contemporary History, 31, no. 3 (July, 1996): 473-474.