Lt. Charles Milton Kates Jr. (September 16, 1919 – December 27, 1944)

157th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division

by Sofia Bastidas

Early Life

Charles Milton Kates Jr. was born in Philadelphia, PA, on September 16, 1919, to Charles Milton Kates Sr. and Helen Busser. His mother, Helen, grew up in Philadelphia, while Charles Sr. had moved to Pennsylvania after growing up in Key West, FL.1 As a teenager, Charles Sr. worked in a cigar factory in Key West.2 In his twenties, he moved to Philadelphia where he married Helen around 1914.3 The couple had three children, Mary (1917), Charles Jr. (1919), and George William (1922). Before the Kates family moved to Florida, they lived with Helen’s parents and Charles Sr. worked as an ironworker in the construction industry.4

Charles Jr. attended Frankford High School in Philadelphia where he played on the tennis team.5 Upon Charles’ high school graduation in 1938, the Kates relocated to Miami.6 Remarkably, in the second half of the Great Depression, Miami had already rebounded and experienced a period of rapid growth.7 Miami’s miracle resulted from the federal government’s response to the economic devastation; it created a vast set of public works programs known as the New Deal. In South Florida, the Public Works Administration (PWA) projects included the construction of the Orange Bowl (originally known as Roddey Burdine Stadium and demolished in 2008) and a highway linking Miami and Key West.8 Charles Sr.’s experience as a construction worker in Philadelphia served him well in South Florida, where the economic possibilities and housing construction greatly improved the family’s prospects.9

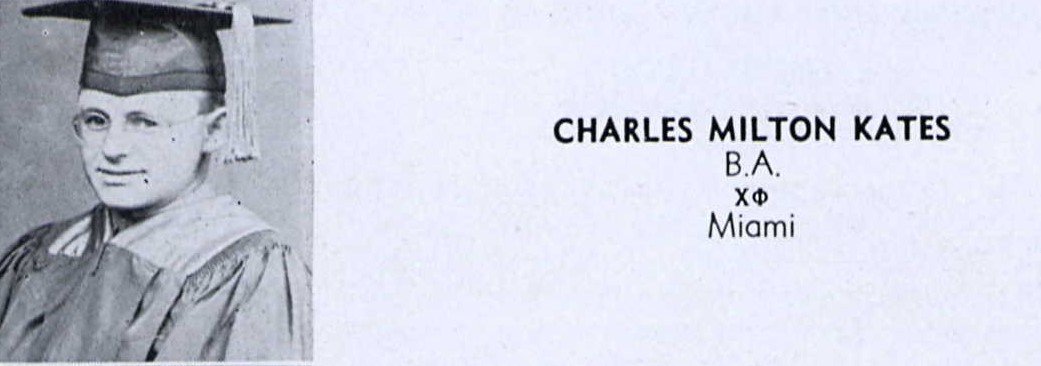

In 1940, Charles attended the University of Florida (UF), and in October, he registered for military service.10 During his college years, Charles served as president of the UF chapter of the Chi Phi Fraternity, noted under his name in his senior photo, and played tennis for the UF Gators. Upon receiving his bachelor’s degree in 1943, Charles began law school at UF.11

According to his family, he was “well respected by his classmates, quiet, intellectual, and a true gentleman with the makings of a judge.”12 Charles met his fiancée, Hazel Martin, after graduating from UF’s law school.13

Military Service

Although Charles registered for service during his sophomore year of college in October 1940, he did not enlist until July 1943, when he left law school to join the US Army as a commissioned officer.14 According to his family, Charles nearly missed qualifying for the service as he had poor eyesight. Eager to join the war effort, he memorized the eye exam to pass the Army medical and join the service.15 In August 1943, Charles entered the Tank Destroyer Officer Candidate School at Camp Hood, TX. In December 1943, he earned his commission as a second lieutenant.16 By the summer of 1944, Charles Kates married Hazel Martin and retrained at Camp Blanding, FL, as an infantry officer in the Infantry Replacement Training Center (IRTC).17

The US Army faced an infantry shortage due to high casualty rates once the European landings in Italy began in September 1943.18 In January 1944, Camp Blanding expanded to meet the demand to replace those who had been killed or wounded by training infantrymen who then joined the front lines.19 These replacement troops became ever more crucial to the war effort following the D-Day landings in June 1944. According to a survey conducted by the US Army Center of Military History, during the six weeks following D-Day, infantry companies lost “nearly sixty percent of their enlisted men and more than sixty-eight percent of their officers.”20 As a result of the high casualty rates American units suffered in combat, the War Department implemented new policies to expand the existing Army personnel replacement system.21 These policies included transferring personnel from other divisions to IRTCs across the country to facilitate the replacement of losses.22 The Army likely transferred Charles from an armored to an infantry division due to this new infantry replacement policy, and the critical need for junior officers to lead men into battle.23

The 45th Infantry Division, also known as the “Thunder Birds,” served in the Seventh US Army during World War II.24 Prior to Charles’s deployment, the 45th Infantry Division participated as one of three American divisions alongside French, British, and Greek divisions, among others, in the massive Allied amphibious invasion of Southern France, known as Operation Dragoon, on August 15, 1944.25 During this operation, the Seventh US Army and the Allies secured the French Riviera and pursued the retreating Germans north and east into the Rhone Valley. In September, the Allies reached the Vosges Mountains, in eastern France, where French, British, and American forces met heavy German resistance.26

Throughout September to November, the 45th continued to move toward the Franco-German border, pushing through the Vosges mountains and into France’s easternmost territory, around Bouxwiller, a small town about twenty-five miles west of the Rhine River.27 To reach Bouxwiller, the 45th had to cross through the Saverne gap on November 23, 1944, a crucial path through the Vosges mountains.28 By December 14, 1944, the 45th secured the town of Langensoultzbach, France, and prepared to move towards Obersteinbach and the German border.29 The 157th regiment crossed the German border on December 16, 1944, the same day that the German forces launched an unexpectedly fierce offensive in the Ardennes region, about 200 miles north toward the Franco-German border. The US Army command quickly responded to what became known as the Battle of the Bulge, or the Second Battle of the Ardennes, by diverting troops from the southern region to support the Allied forces in Ardennes. The 157th, however, remained in place to help hold the line further south along the German border.30

As winter approached, Allied infantry units’ shortages went from critical to severe. It was at this time that Charles Kates entered into the 157th Infantry Regiment, coming from the 3rd Replacement Battalion. Prior to his deployment into the 157th, on December 18, 1944, Company C of the First Battalion in the 157th Infantry Regiment pushed forward into Bundenthal, Germany, a small town on the Franco-German border. Encountering heavy resistance, German forces pinned down Company C from all sides with artillery and machine gun fire as the men attempted to establish communication with Allied units nearby, including the rest of the 157th regiment. Company G from the Second Battalion attempted to rescue the First Batallion’s Company C trapped in Bundenthal, but Company G also became pinned down in and around the town. For six long days the men of Company G and C defended their encircled position until First Battalion’s Company A and Company B rescued them on December 24, 1944.31

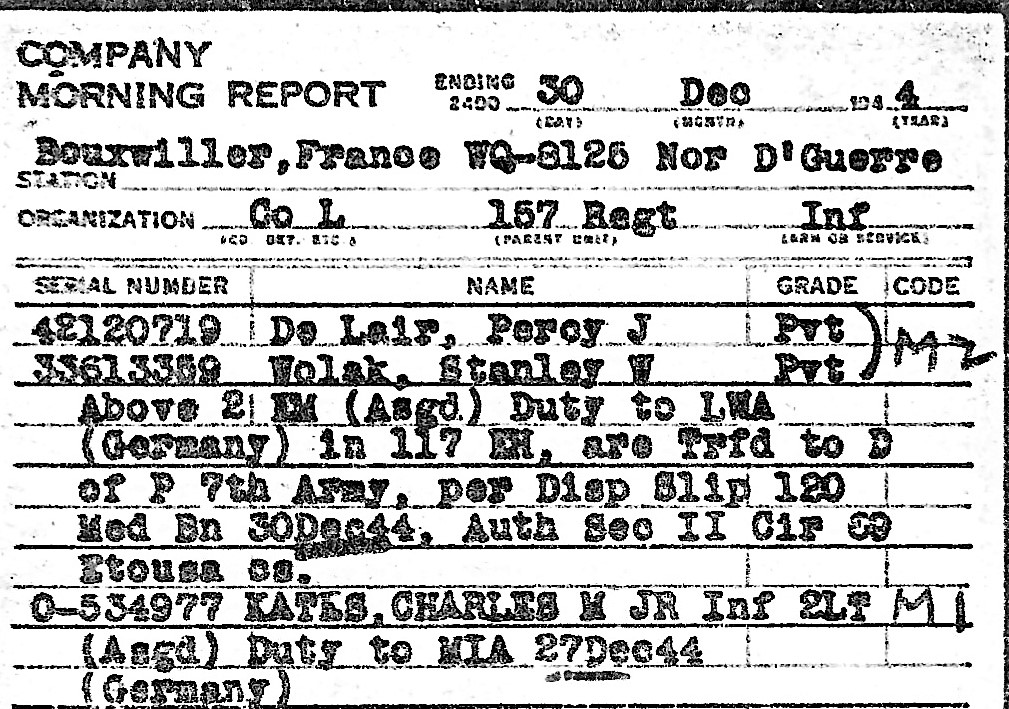

Three days prior to the rescue, Charles Kates deployed to L Company of the 157th Infantry Regiment of the 45th Infantry Division around the Company’s defensive position in Nothweiler, Germany.32 With the men who had been trapped in Bundenthal rescued, the 157th retreated to defensive positions in the high ground north of Obersteinbach by December 27, 1944, north of Alsace and on the German Border. In the final days of 1944, Charles and the 157th repulsed German attacks around Obersteinbach, and secured more defensive positions around Niedersteinbach, France.33 On December 27, 1944, the 157th listed Second Lieutenant Charles Kates missing in action (MIA), as we see here in the morning report issued from headquarters behind the frontline.34 On January 8, 1945, the Army changed Charles’ status to killed in action (KIA).35 Charles and the other men who went missing with him became a handful of more than 80,000 casualties the US suffered during December and January of 1944 to 1945.36 Soldiers fighting in the Low Vosges area in Alsace faced miserable conditions at the time of Charles Kates’s death. Many men of the 45th Infantry spent the end of December, outside in frozen foxholes, suffering from frostbite and frequent German artillery barrages.37 Of the 80,000 US casualties, the 157th Infantry regiment suffered sixty-nine deaths, 379 wounded, and thirty MIA. In addition, the Germans took 487 men of the 157th as prisoners of war in December 1944.38

Legacy

Lt. Charles Kates rests in the Lorraine American Cemetery only sixty miles from where he fell fighting Nazi forces on the Franco-German border. The 45th Infantry Division continued fighting, engaging in Operation Nordwind, the last German-led offensive, which began the day after Charles’s death. Then, in spring 1945, the Thunderbirds liberated Dachau, one of the first and largest concentration camps in Central Germany. As a result, Charles’ Third Battalion of the 157th Regiment was one of the first battalions to liberate and witness the depravity of the Nazi prison system.39

Charles was survived by his parents, brother George, sister Helen Lucille, and wife Hazel. Both of his parents lived until 1981; they are buried in a companion plot in the Southern Memorial Park Cemetery in north Miami.40 His sister, Helen, married Rube R. Dossey in 1942.41 Helen and Rube stayed in Dade County, where Helen worked as a bookkeeper and Rube as an aircraft mechanic. In honor of her brother, Helen and Rube named their son Charles.42 Helen lived until 1991, and her spouse lived until 1988. Both Helen and her husband are buried in a companion plot near her parents in Southern Memorial Park Cemetery.43

Charles’ brother George Kates also served in World War II, fighting in the Pacific theater as a Technical Sergeant in the US Army Air Forces. Upon his discharge from the military, George attended the University of Florida on the GI Bill and studied law to honor the memory of his brother. George passed away in 2012; he is buried in the Bakersfield National Cemetery, in the Mojave Desert in California.44

The sacrifice of the Thunderbirds who fought and died in World War II is not forgotten. An entire museum in Oklahoma City, OK is dedicated to the 45th Infantry. As well, numerous groups, including the “45th Infantry Division in World War II Reenactors and Venturing Crew,” carry out the work of keeping the memory of these men, who made the ultimate sacrifice, alive.45 Charles Kates was one of the 1,831 soldiers of the 45th who died in Europe, but his story lives on through this family and these organizations dedicated to remembering their legacy.46

1 “1920 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com, accessed on September 20, 2022), entry for Charles Milton Kates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

2 “1910 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com, accessed on September 20, 2022), entry for Charles Milton Cates, Key West, Monroe, Florida.

3 “1920 U.S. Census.”

4 “1920 U.S. Census.”

5 “U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-2016,” database, Ancestry (www.Ancestry.com, accessed October 02, 2022), entry for Charles Milton Kates Frankfort High School.

6 “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com, accessed on February 25, 2023), entry for Charles Milton Kates Jr, Florida

7 John A. Stuart and John F. Stack, The New Deal in South Florida: Design, Policy, and Community Building, 1933-1940 (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2008), 106.

8 Stuart and Stack, The New Deal, 61

9 J. Kenneth Ballinger, Miami Millions: The Dance of Dollars in the Great Florida Land Boom of 1925 (Miami, FL: Franklin Press, 1938), 5.

10 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com, accessed October 02, 2022), entry for Charles Milton Kates, service number 0534977.

11 “Six Trek to Altar,” The Miami Herald (Miami, FL), March 16, 1944, Newspapers.com

12 Email correspondence with Kathe Davis, September 22, 2022. Ms. Davis is Lt. Charles Kates’ niece. We would like to thank Ms. Davis; we are grateful for her assistance with this project.

13 “Six Trek to Altar.” We have been unable confirm the date of Charles’ graduation; the 1944 newspaper article listed him as graduated with a degree in law, so he may have graduated after enlisting.

14 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947.”; “United States of America World War II Enlistment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 1, 2023), entry for Charles Milton Kates.

15 Email correspondence from Kathe Davis, September 22, 2022.

16 “Kates Training TX,” The Miami Herald (Miami, FL), August 27, 1943, Newspapers.com.

17 W. Stanford Smith, Camp Blanding: Florida Star in Peace and War (Varina, NC: Research Triangle Publishing, 1998), xiii; “Six Trek to Altar,” The Miami Herald (Miami, FL), March 16, 1944, Newspapers.com.

18 Roland Ruppenthal, Logistical Support of the Armies, Vol. 2, September 1944-May 1945 (Washington D.C: Center of Military History, 1995), 310, 313.

19 Smith, Camp Blanding, 117.

20 Harry Yeide, The Tank Killers (Havertown: Casemate Publishers, 2004), 127.

21 Ruppenthal, Logistical Support, 320.

22 Leonard L. Lerwill, The Personnel Replacement System in the US Army, (Washington D.C: Department of the Army, 1954), 452.

23 Ruppenthal, Logistical Support, 318.

24 “The 45th Infantry Division During World War II,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed May 20, 2023, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-45th-infantry-division.

25 Anthony Tucker-Jones, Armored Warfare from the Riviera to the Rhine (S. Yorkshire: Pen & Sword, 2016), 38; Yeide, The Tank Killer, 187.

26 Tucker-Jones, Armored Warfare from the Riviera to the Rhine, 73; Army & Navy, The History of the 157th Regiment (Baton Rouge: Army & Navy Publishing Company, 1946), 113.

27 “Order of Battle of the 45th Infantry Division,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed February 25, 2023, https://history.army.mil/documents/eto-ob/45id-eto.htm; Army & Navy, The History of the 157th Regiment, 121, 125; Morning Report, December 30, 1944.

28 Shelby L. Stanton, Order of Battle: U.S. Army World War II (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1984), 134.

29 “Order of Battle of the 45th Infantry Division.” Langensulzbach is now called Langensoultzbach.

30 “157th Combat History,” 45th Infantry Division World War II Reenactors, accessed May 20, 2023, https://www.45thdivision.org/CampaignsBattles/157thCombat.htm.

31 Email correspondence with LTC. Hugh Foster, October 24, 2022.

32 Email correspondence with Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Foster, October 24, 2022.

33 Emil P. Navta, Historical Record of the 157th Infantry Regiment, 1 December 1944 to 31 December 1944 to Commanding General of the Seventh Army (Forty Fifth Infantry Division Headquarters: January 11, 1945), 12. We would like to thank LTC. Hugh Foster and Leonard Cizewski for providing a digitized version of this historical record; Email correspondence with LTC Hugh Foster, October 24, 2022.

34 “Morning Report, 157th Infantry Regiment, Company L, December 25, 1944.” Again we thank LTC. Hugh Foster and Leonard Cizewski of the 45th Infantry Division in WWII Association for their assistance and for providing copies of the morning reports which are not widely available in a digital format; Navata, Historical Record of the 157th Infantry Regiment, 12.

35 Army & Navy, The History of the 157th Regiment, 128; Morning Report, 157th Regiment, Company L, January 8, 1945. We thank LTC. Hugh Foster and Leonard Cizewski for providing a digitized version of this morning report.

36 Ruppenthal, Logistical Support, 316, 317, 321; “Battle of the Bulge,” The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, accessed May 20, 2023, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/battle-of-the-bulge#:~:text=In%20the%20Battle%20of%20the,the%20Battle%20of%20the%20Bulge.

37 Flint Whitlock, The Rock of Anzio: From Sicily to Dachau, A History of the 45th Infantry Division (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1998), 335.

38 Navta, Historical Record of the 157th Infantry Regiment, 14.

39 Army & Navy, The History of the 157th Regiment, 163;

40 “Charles Milton Kates and Helen H. Busser Kates,” FindAGrave.com, accessed April 30, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/211831002/charles-milton-kates, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/211838849/helen-h-kates.

41 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 30, 2023), entry for Helen Lucille Kates and Rube R. Dossey, August 7, 1942.

42 “1950 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 30, 2023), entry for Rube R., Helen L., and Charles B. Dossey, Opa-Locka, Dade County, Florida.

43 “Helen Lucille Kates Dossey and Rube Rippling Dossey,” FindAGrave.com, accessed April 30, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/211840312/helen-lucille-dossey, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/211840291/rube-rippling-dossey.

44“National Gravesite Locator,” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, entry for George W. Kates, accessed April 30, 2023, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/ngl/; Email correspondence with Kathe Davis. George’s daughter Kathe, Charles’ niece, also graduated from the University of Florida School of Law.

45 See https://45thdivisionmuseum.com/ as well as the 45th Infantry Division in WW2 Association, http://www.ibiblio.org/45wwiiresources/. There is also a reenactment group, see https://www.45thdivision.org/.

46 “The 45th Infantry Division During World War II,” United State Holocaust Memorial Museum.