Pvt. 1st Class Thomas Vasco Johnson (April 22, 1911 – August 29, 1944)

179th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division

By William James Breska and Elizabeth Klements

Early Life

Thomas Vasco Johnson was born on April 22, 1911, to James and Allie Johnson.1 Thomas was the oldest of five children: Laverne (1912), James Perry (1915), Helen Louise (1918 – 1921), and Allie Mae (1927). Thomas and his brother often went by their middle names, Vasco and Perry, probably because they shared their names with other family members. James and Allie Johnson were both born in Florida and settled down in Glen St. Mary, Baker County, FL after they married. James worked in agriculture, at first as a laborer at a plant nursery before renting his own farm sometime between 1920 and 1930.2 Baker County, which borders Georgia, was home to a diverse and ever-growing agricultural sector in the early twentieth century. While we are not sure what the Johnson family grew, corn and peanuts were the leading crops at the time, followed by pecans, peaches, pears, and plums.3

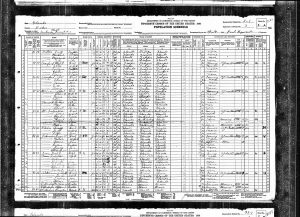

The Johnson family educated their children, but they understood that agriculture provided the best chance for their sons to succeed. As seen in this 1930 census, all the Johnson children attended school into their late teens, but only reached a seventh or eighth grade-level education.4 This was not uncommon for the time, especially in rural areas. According to a brief history of Baker County, until the 1950s “only a handful could boast of higher education while the majority…did well to recognize their own names.”5 The average rural American child only attended school for a few years, where the age ranges for students differed greatly. Moreover, rural schools lacked a formal structure, including time off for agricultural work, and the teachers themselves often were without formal training.6 Thomas and James likely worked on their father’s farm once they were old enough and attended school irregularly, when he could spare them.

Their assistance must have been especially valuable throughout the 1930s, when the children were in their late teens and early twenties, as the Great Depression affected every level of economic activity in the country.7 This may have been why in 1940, Thomas, aged twenty-eight, worked and lived with his parents and youngest sister, Allie. Laverne moved away, likely to marry and start her own family.8 James married Mabel Ritch and seemed to split his time between his father’s farm and his own in nearby Lulu, FL, next door to his father-in-law’s farm.9

Military Service

Thomas registered for the draft in October 1940, and even though his labor must have continued to play a vital role in his family’s farm, the US Army called him into service shortly afterward, on February 19, 1941.10 Thomas, at twenty nine years old, entered the service at Camp Blanding, FL, and then became a private in 179th Infantry Regiment, Company C, of the famed 45th Division, with which he trained at Fort Sill, OK, Camp Barkley, TX, Fort Devens, MA, Pine Camp, NY, and Camp Pickett, VA.11 According to the National World War Two Museum, “basic training taught a new recruit to think of himself less as an individual and more as an integral part of his unit.”12 In other words, becoming a soldier was less about an individual’s survival or personal gain; but working as a band of brothers who looked out for one another, followed orders, and sacrificed for the greater good.

The 45th Division trained for over two years before shipping out for North Africa in June 1943. Allied forces secured the region in May 1943 and intended to use it as a staging area for the invasion of Italy, beginning with the island of Sicily. The 45th landed on Sicily on July 10, 1943, and fought for a month to secure the island. The Allies’ success there led to the collapse of Italy’s fascist regime, and the country’s surrender on September 3, 1943.13 The fight for Italy, however, continued as German forces mounted a defense. From September to January, the 45th Division and other Allied forces pushed up the Italian peninsula. They faced mountainous coastlines, which gave the Germans favorable defensive positions and made transportation difficult and slow.14

By January 1944, the Allied forces reached an impasse and could not push past the Gustav Line, a German front stretched across the peninsula to the south of Rome. They decided to bypass this line by landing at the beaches of Anzio, a coastal town above the Gustav Line and about thirty miles south of Rome.15 The Allied forces landed at Anzio on January 22, with the 45th Division in reserve. It looked like it would be an easy operation, but it backfired when German forces pinned down the Allies at Anzio for 135 days, at the cost of 7,000 soldiers killed and 36,000 wounded. After months of hardship and despite the massive losses, the Allied forces managed to break out of the Anzio beachhead and capture Rome on June 4th, 1944.16 This would not have been possible without the efforts of the Moroccan, South African, Indian, Polish and Canadian forces who, along with the Americans, valiantly pushed through the Gustav line after a series of attacks on the town of Monte Cassino, and forced the German troops away from Rome by the end of May, 1944.17

Just one month after the Allies took Rome, the 45th Division participated in Operation Dragoon, the mission to liberate Southern France, beginning on August 15, 1944. The US 3rd, 36th and 45th Infantry Divisions fought under the command of Major General John W. O’Daniel. After some debate, the Allied leadership selected the seaside town of St. Tropez, about thirty miles east of Toulon, and the surrounding area as the optimal place along the French coast for the amphibious landing. On August 15, the 45th Division landed near the town of Ste. Maxime, just east of St. Tropez.18 In the initial days of the invasion, Thomas Johnson, the 45th Division and the rest of the Allied forces pushed north and east, into the French mainland, with only light German resistance. This was because the Germans expected the Allies to land at the big port cities of Marseille or Toulon, and the French Resistance launched guerilla attacks to cut German lines of communication, preventing an organized German response to the landings.19

After a few attempts to hold their ground, the German High Command ordered its troops in southern France to retreat north. In the weeks following the August 15 landings, Allied troops moved rapidly north in order to cut off the German Army’s escape route. Johnson’s 179th Regiment travelled parallel to the German’s escape route, securing important bridges across the Rhone River. By the end of August, they reached the town of Meximieux, northwest of the city of Lyon.20 On August 29, 1944, Thomas Johnson died in the line of duty from an abdominal injury caused by artillery shells.21 His regiment was not in contact with German forces between August 22 and September 1, so Johnson may have died in an unrecorded attack or an ammunition-related accident.22 After Johnson’s death, his comrades in arms pushed north toward the Franco-German border and participated in the invasion of Germany. In their last combat mission, the 45th Division took the city of Munich in April 1945 and helped liberate the prisoners at the nearby concentration camp of Dachau.23

Legacy

The US Army granted Pvt. First Class Thomas Vasco Johnson a posthumous Purple Heart for his death in combat and buried him in a temporary cemetery. After the war ended, France granted the US land to establish five cemeteries for the soldiers who died on French soil, just as they had done after World War I. Johnson’s final resting place is at one of these cemeteries: section B, row one, grave nine of the Rhone American Cemetery.24 He was survived by his parents James (1966) and Allie (1968), and his siblings Laverne (2000), James Perry (1977) and Allie Mae.25

In 1965, the state of Oklahoma created the 45th Infantry Division Museum to honor the service and sacrifices of the men like Thomas Johnson who fought and died for their country.26 The significance of these soldiers’ accomplishments stands the test of time through this museum and those who walk its halls.

1 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 20, 2021), entry for Thomas Vasco Johnson; “1920 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/14627390:6061: accessed March 20, 2021), entry for Vasco Johnson, Baker County, Florida.

2 “1920 U.S. Census;” “1930 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 20, 2021), entry for James Johnson, Baker County, Florida. For Helen Louise, see also “Helen Louise Johnson,” Find a Grave, accessed July 21, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/76467288/helen-louise-johnson.

3 W. C. Winger, “History of Baker County,” Florida Memory, accessed March 23, 2021, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321077?id=2.

4 “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 23, 2021), entry for James Johnson, Baker County, Florida. The 1930 Census indicated that Thomas (19), Laverne (17), and James (15) still attended school.

5 Gene Barber, “County History Relatively Unknown, But Unique,” The Baker County Press (Baker County, Florida), June 24, 1976, Rootsweb.com, accessed March 20, 2021, https://sites.rootsweb.com/~flbakehs/gene76.html#flrecord.

6 “Education In the 20th Century,” Britannica, accessed March 20, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/education/Education-in-the-20th-century.

7 “Great Depression and the New Deal,” Exploring Florida, accessed July 14, 2021, https://fcit.usf.edu/florida/lessons/depress/depress1.htm.

8 “1940 U.S. Census,” entry for Thomas Johnson.

9 “1904 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed July 14, 2021), entry for Perry Johnson, Columbia County, Florida. See also “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 20, 2021), entry for James Perry Johnson, serial number 127.

10 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” entry for Thomas Vasco Johnson; “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 26, 2021), entry for Thomas V. Johnson, service number 34023581.

11 45th Division Museum, “History of the 45th Division,” accessed March 26, 2021, http://45thdivisionmuseum.com/index.php/history/history-of-the-45th-infantry/; “Headstone Inscription and Internment Record,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 26, 2021), entry for Thomas V. Johnson, service number 34023581; Warren P. Munsell, The Story of a Regiment: A History of the 179th Regimental Combat Team (U.S. Army, 1946), 150, https://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/34/.

12 National WWII Museum, “Training the American GI,” accessed March 26, 2021, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/training-american-gi.

13 Munsell, The Story of a Regiment, 10 – 22.

14 “The 45th Infantry Division: World War II in Sicily and Italy,” Oklahoma Historical Society, accessed March 26, 2021, https://www.okhistory.org/learn/45th2; “45th Infantry Division – Thunderbird,” US Army Divisions, accessed July 15, 2021, https://www.armydivs.com/45th-infantry-division.

15 “Campaigns of the Mediterranean Theater in World War II,” US Army Divisions, accessed July 15, 2021, https://armydivs.squarespace.com/mediterranean-theater#anzio.

16 “The 45th Infantry Division: World War II in Sicily and Italy.”

17 C. Peter Chen, “Battle of Monte Cassino,” World War II Database, accessed July 19, 2021, https://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=312.

18 Jeffrey J. Clarke, Southern France: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 2019), 9 – 16, https://history.army.mil/html/books/072/72-31/CMH_Pub_72-31(75th-Anniversary).pdf.

19 Clarke, Southern France, 13 – 24.

20 Munsell, The Story of a Regiment, 71 – 77.

21 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records;” “World War II Hospital Admission Card Files,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Thomas V. Johnson, service number 34023581, August 1944.

22 Munsell, The Story of Regiment, 71 – 77.

23 “Liberation of Dachau,” The 45th Infantry Thunderbird Museum, accessed July 22, 2021, http://45thdivisionmuseum.com/index.php/exhibits/liberation-of-dachau/.

24 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records;” “Cemeteries & Memorials,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed March 29, 2021, https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials.

25 “James R. Johnson Jr.,” Find a Grave, accessed March 29, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/76440081/james-r.-johnson; “Allie Roberts Johnson,” Find a Grave, accessed March 29, 2021, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/76440097/allie-johnson; “Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?dbid=7338&h=1769538&indiv=try: accessed July 21, 2021), entry for James Perry Johnson; “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/35992066:60901: accessed July 21, 2021), entry for Laverne Mann.

26 “About the 45th ID Museum,” The 45th Infantry Thunderbird Museum, accessed March 20, 2021, http://45thdivisionmuseum.com/index.php/about-the-museum/.