Pvt. Joseph “Joe” Neal Johnson Jr. (November 16, 1924 – December 4, 1944)

101st Infantry Regiment, 26th Infantry Division

by James Boyle

Early Life

Joseph “Joe” Neal Johnson Jr. was born in McKenzie, TN, on November 16, 1924, to Joseph Neal Johnson and Maye Cannon Johnson, almost exactly one year after his parents married.1 By 1934 the family was living in Memphis, TN, and in 1937 they moved farther south, buying a house in St. Petersburg, FL.2 In St. Petersburg, Joseph Sr. became manager of a Dodge Plymouth car dealership’s sales floor, earning a yearly salary of $2700. This was nearly double the national average salary of $1,368 a year.3 Maye took care of their home, and Joe, their only child, attended St. Petersburg High School which was just a block down the road from their new home.4

According to his 1943 senior yearbook entry, seen here, Joe was known for “waltz[ing] divinely and on skates too.”5 In school, he participated in several clubs and extracurricular activities, including the Dramatic Club and a charity show titled “Ladies’ Aid” which featured acts from all around the community. He also served as a captain in the school’s Victory Corps, which was designed to get students involved in the war effort. The Victory Corps separated students into military-style units. Many schools participated, and each made up its own division. The St. Petersburg High School division consisted of three battalions, each representing a different class: sophomores, juniors, and seniors. Each homeroom made up a company headed by a captain, like Joe, appointed by the teacher, with smaller groups making up squads. Members of the Victory Corps took special classes designed to give them experience in various aspects of the war effort, from knitting blankets to send to wounded soldiers, to learning Morse code, and even devising solutions for various problems that might arise in the post-war world. Most of these classes seem to have been co-ed, with yearbook pictures showing boys and girls working together, although there are no boys pictured in the cooking, scrapbooking, or nursing classes, indicating that the tasks may have been determined by gender norms.6

Military Service

Joe graduated from St. Petersburg High in June 1943, and the US Army called him to service a few months later. Three days before his nineteenth birthday, he reported to Camp Blanding, near Jacksonville, for training.7 Camp Blanding initially trained new units, with accommodations available for more than two full infantry divisions, approximately 30,000 men, but in 1943 the Army transformed it into an Infantry Replacement Training Center (IRTC) designed to help replenish units in Europe that had suffered losses.8 Camp Blanding was the second largest IRTC in the US and by the end of the war; it had trained nine full infantry divisions (at approximately 15,000 men each), various specialized units, and 165,224 replacement troops, for a grand total of over 300,000 men. The camp also included an impressive and brand-new hospital and a prison camp for German prisoners of war.9

When not participating in training exercises, soldiers stationed at Camp Blanding enjoyed various forms of recreation and entertainment. Several concerts entertained the troops there over the course of the war, and regular radio broadcasts were produced on site for various stations in the area. Sports proved very popular among the men, with boxing being among the most popular. Soldiers sometimes used the boxing ring as a place to settle differences without getting into trouble. Not all the soldiers, however, shared the same experiences at Camp Blanding. While the US officially prohibited discrimination in the armed forces in 1941, it still shaped the experiences of black and white soldiers, to whom the camp authorities assigned different types of jobs, provided different qualities of lodging, and held to different standards of behavior.10

Upon completing his training at Camp Blanding, Pvt. Johnson shipped out to England with an engineer unit in the summer of 1944. At some point between his deployment and early November 1944, he was transferred to the 101st Infantry Regiment, part of the 26th Yankee Infantry Division, and sent to France.11 The Yankee Division left the US in August 1944 and landed at France’s northern coast on September 7, 1944, about three months after the first Allied landings there on June 6, 1944.12 Along with the rest of the 26th, the 101st Infantry participated in Gen. George Patton’s Lorraine Campaign, a continuation of the Allied push into France following the success of the D-Day invasion.13

Lorraine is a region in the northeast of France, bordering Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany. Patton’s goal for this campaign was to advance to the Ruhr River, just north of the Rhine River on the French-German border, and eventually defeat the German fortifications known as the West Wall, or Siegfried Line, all of which he anticipated would take ten days. From there, he wanted to move quickly through Germany and take Berlin. Well known for his unorthodox methods of commanding troops, Patton considered himself self-taught in the subject of military strategy and his decisions frequently put him at odds with other leaders, including Gen. Dwight Eisenhower. As the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, Eisenhower had the ability to limit Patton’s controversial actions, and went as far as rationing Patton’s fuel supply to keep him from advancing at a suicidal rate. Due to these fuel shortages and stronger than expected German resistance, the campaign took much longer than expected—more than two months rather than Patton’s projected ten days.14

During the Lorraine Campaign, the Allies liberated the fortified cities of Metz and Nancy, removing some of Germany’s strongest defenses in eastern France. Beyond the West Wall was the Ruhr Valley, which held a large portion of Germany’s manufacturing and natural resources. Critical to the Allies overall strategy, a breakthrough here would bring Germany’s munitions factories to a halt. Metz was the more strongly fortified of the two, and since the cities were too far apart to provide support to each other with their artillery emplacements, Patton made the decision to take Nancy first. Within ten days in early September, 1944, Patton’s troops won the city and punctured a hole in the German defenses. The battle for Metz, however, took almost the entire month of November, and isolated pockets in the area held out until mid-December 1944.15

After reaching France in September, the 101st deployed to Arracourt, a small town near the recently liberated Nancy and about thirty miles southeast of Metz. They began combat engagements in the area on November 8, 1944, assisting in the battle for Metz by pushing the nearby German forces back to the Franco-German border. The 101st moved eastward, first taking the town of Moyenvic and then an important defensive position known as “Hill 310,” where the fighting was so intense the men there called it “Purple Heart hill.” On November 13, the 101st received additional soldiers and took Bedestroff, after which its battalions split up to liberate different towns in the area.16

On the first of December, the 101st reassembled to take part in the attack and capture of the town of Sarre-Union, about thirty miles east of Arracourt, joined by the 104th Infantry and the 4th Armored Division. The battle for the town began with support from two squadrons of fighter planes covering the regiment’s push to the edge of the town. The men of the 101st engaged in house-to-house combat for three days, dodging artillery shells as they pushed the Germans out of the town. On December 3, the Allies nearly secured Sarre-Union when the Germans launched a counterattack, sending six tanks and about a hundred soldiers to the town. The Allies responded with massive artillery fire, and, with the support from the 4th US Armored Division, the 101st and 104th helped repel the German counterattack in a few hours and consolidate their hold on the town.17 Pvt. Johnson was wounded at some point during the fighting, suffering wounds from artillery shrapnel in two areas around his neck and spine. He died of his wounds on December 4, 1944, at the age of twenty.18

Legacy

The eventual victory at Metz marked the end of the Lorraine Campaign, which further crippled the crumbling German supply system, although it was not the swift end Patton predicted. After Pvt. Johnson’s death, his fellow soldiers moved to the Ardennes to stop the attempted German breakthrough at the Battle of the Bulge. In March 1945, the 26th Division assisted in the final Allied push into Germany. Over the next two months, they crossed Germany and into Austria where, on May 4, they liberated the Gusen concentration camp, a subcamp of the Mathausen camp complex. The division then moved northeast into Czechoslovakia, where they remained after Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945.19

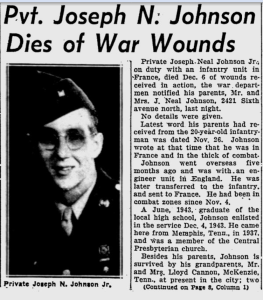

Joseph Neal Johnson Jr. received a purple heart posthumously for the fatal injuries he suffered in battle, and he is buried in Lorraine American Cemetery in St. Avold, France, Plot C, Row 23, Grave 31.20 When word of Pvt. Johnson’s death reached home, several newspapers in the Tampa Bay area, including the Tampa Bay Times and the St. Petersburg Evening Independent, published his obituary, seen here. This obituary reported that Joe had written to his parents on November 26, ten days after his twentieth birthday and eight days before his death, where he described the combat conditions of the Lorraine Campaign. Joe Sr. and May must have received it just before or after the Army informed them of Pvt. Johnson’s death. His grandparents were visiting in St. Petersburg when the news arrived, meaning two generations of his family were able to be together to support one another as they grieved.21 By the time of the 1945 Florida state census, Joseph Sr. had become a distributor for Gordon Foods in the St. Petersburg area, but it seems clear that Joe’s parents, who must have been devastated by the loss, eventually moved back to McKenzie, TN to be closer to their extended family. Following their return to McKenzie, Joseph Sr. became manager of a lumber company before his death from a heart attack in 1963.22

1 “U.S. World War II Draft Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com: accessed April 29, 2021), entry for Joseph Neal Johnson Jr.; “Marriage License: J. Neal Johnson and Maye Cannon,” database, FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org: accessed 29 April 2021), entry for J Neal Johnson and Maye Cannon, McKenzie, Carroll County, Tennessee.

2 “1940 US Census,” database, Familysearch.org (http://www.familysearch.org: accessed February 29, 2021), entry for J. Neal Johnson Jr., St. Petersburg, Pinellas County, Florida; “Pvt. Joseph N. Johnson Dies of War Wounds,” The Evening Independent, December 18, 1944, GoogleNews.com.

3 “1940 US Census;” Diane Petro, “Brother Can You Spare a Dime – The 1940 Census: Employment and Income,” Prologue 44, no. 1 (Spring 2012), https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2012/spring/1940.html.

4 “1940 US Census.”

5 “U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 29, 2021), entry for St. Petersburg High School, No-So-We-Ea 1943.

6 Ibid.

7 “U.S. World War II Army Enlistment Records,” database, Fold3.com (https://fold3.com: accessed April 29, 2021), entry for Joseph Neal Johnson Jr., St. Petersburg, serial number 34796267.

8 “History of Camp Blanding,” Camp Blanding Joint Training Center, accessed March 25, 2021, https://fl.ng.mil/Camp-Blanding/Pages/History.aspx.

9 George E. Cressman Jr., “Camp Blanding Station Hospital in the War Years,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 93, no. 4 (Spring 2015): 553 – 586.

10 Cressman, “Camp Blanding Station Hospital;” Jon Evans, “The Origins of Tallahassee’s Racial Disturbance Plan: Segregation, Racial Tensions and Violence During World War II,” Florida Historical Quarterly 79, no. 3 (Winter 2001): 346 – 364.

11 “Pvt. Joseph N. Johnson Dies of War Wounds.”

12 “U.S. World War II Army Enlistment Records;” Shelby L. Stanton, Order of Battle, U.S. Army, World War II (Novato: Presidio Press, 1984), 101-102. The 26th got its nickname “Yankee” Division in WWI, when it was created from the National Guard of six New England states.

13 “101st Infantry Regiment Battle Honors,” The “Yankee” Division in World War II, accessed January 21, 2022, archived May 16, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20160516181325/http://yd-info.net/page5/page21/.

14 John A. Adams, The Battle for Western Europe, Fall 1944: An Operational Assessment (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 198 – 232.

15 Ibid.

16 “101st Infantry Regiment Battle Honors;” “26th Infantry Division History, World War II,” The “Yankee” Division in World War II, accessed January 24, 2022, archived March 31, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20160331012618/http://yd-info.net/page2/index.html#Metz.

17 “26th Infantry Division History, World War II.”

18 “U.S. World War II Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Fold3.com (https://fold3.com: accessed April 29, 2021), entry for Joseph Neal Johnson Jr., service number 34796267; “World War II Honor List of Dead and Missing Army and Army Air Forces Personnel from Florida, 1946,” database, Fold3.com (https://fold3.com: accessed April 29, 2021), entry for Joseph N Johnson Jr., Pinellas County, Florida; “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 29, 2021), entry for Joseph N. Johnson, Jr.

19 “26th Infantry Division History, World War II;” “The 26th Infantry Division during World War II,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, accessed January 25, 2022, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-26th-infantry-division.

20 “Interment Record: Joseph N. Johnson Jr.,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed April 29, 2021, https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/johnson=joseph-4.

21 “Pvt. Joseph N. Johnson Dies of War Wounds.”

22 “1945 Florida State Census,” database, Familysearch.org (http://www.familysearch.org: accessed 29 February 2021), entry for J. Neal Johnson., St. Petersburg, Pinellas County, Florida; “Certificate of Death: J. Neal Johnson,” database, FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org: accessed 29 April 2021), entry for J Neal Johnson, McKenzie, Carroll County, Tennessee.