Tec 5 Albert McKnight Jackson (July 11, 1910 – November 12, 1944)

Company B, 25th Engineer Battalion, 6th Armored Division

by Nicholas Moreschi

Early Life

Albert McKnight Jackson was born in Winter Park, FL, on July 11, 1910, to Herbert Vernon Jackson and Clydia Jackson.1 His older sibling, Herbert Vernon Jackson Jr., had joined the family two years before him on May 19, 1908, in Orlando, FL.2 Albert Jackson’s father, Herbert Vernon Jackson Sr., was born in Georgia on April 26, 1876, to L.H and Fannie Jackson. Albert Jackson’s mother, Clydia, was born in Texas in 1881.3 Sometime around 1910, Clydia and Herbert met and settled down in Orange County, FL, where Herbert Jackson managed an orange farm while Clydia took care of their young children, Herbert Jr. and Albert.4 Many men living in Central Florida worked in the orange industry, especially during this time when orange production skyrocketed, becoming one of Florida’s primary exports.5

A few years later, the family established their residence in Umatilla Lake, Lake County, FL.6 In 1918, at the age of forty-two, Herbert Vernon Jackson Sr. registered for the World War I draft as part of the third wave of registrations held on September 12 for men aged eighteen through forty-five.7 With the signing of the armistice in November, Herbert Sr. did not serve in World War I. Unfortunately, just two years later, at the age of thirty-eight, Albert’s mother, Clydia Jackson, suddenly passed away.8

Shortly after they graduated from high school, Albert and his brother, Herbert Jr., moved out of the greater Orlando area. Herbert Jr. moved to San Francisco after joining the Army, and Albert moved to Dixie County, FL, working as a lumberer. Florida experienced a lumbering boom at the start of the twentieth century, which declined when lumber production slowed down during the Depression, and many workers who were not permanently established in the company towns moved to other areas around Florida. Sometime between 1935 and 1940, Albert came back to live with his father, who must have retired by that time.9 By 1940, Albert seems to have supported his father working as a truck driver, earning over $780 a year.10

Military Service

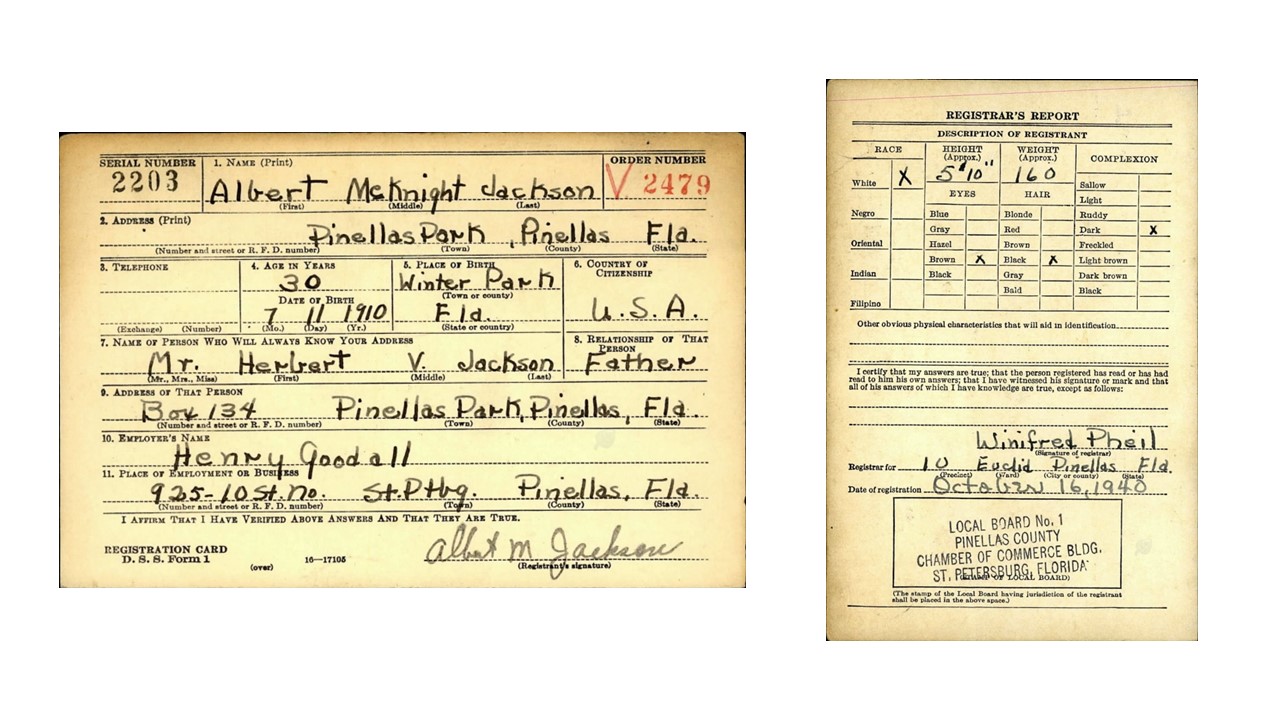

Albert Jackson registered for the draft on October 16, 1940. Although Jackson registered for the draft, he volunteered to enlist in the Army only a few months later, in December, 1940. The Army sent Jackson to Camp Blanding for initial training.11 Jackson may have been inspired by his brother to volunteer as Hebert Jackson Jr. was already a soldier by April 1940, stationed at the Presidio Camp in San Francisco, CA.12 However, at some point in 1941, the Army released Jackson from service and he returned to civilian life. Jackson returned to Camp Blanding in 1942, where he re-enlisted on March 19.13 A vital base for the Army in World War II, overall, 800,000 men trained at Camp Blanding over the course of the war, a total of nine infantry divisions.14

Jackson became a Technician 5th Grade and was assigned to the 25th Engineer Battalion, attached to the 6th Armored Division (AD), nicknamed the “Super Sixth.”15 The 6th AD activated on February 15, 1942, at Fort Knox, KY. While we do not know when Jackson joined the division, the 6th AD trained intensively at various locations throughout the US for twenty-nine months. It finally boarded transports in the New York harbor on February 10, 1944, to cross the Atlantic Ocean, taking part in one of the largest convoys of war. The troops of the 6th AD remained for four months in the northwest countryside of London, England, before departing for France, landing at Utah Beach on July 18, 1944, using the ports Allied engineers constructed along the Normandy coast following the D-day Invasion on June 6.16 From July 25 to July 31, the 6th AD participated in Operation Cobra, part of the battle for Normandy.

After fierce combat, especially around Avranches, Allied forces finally broke out of the Cotentin Peninsula, opening the road to penetrate further west to Brittany and east toward Paris. The 6th AD received orders to turn west, advancing through the Brittany Peninsula following two routes. Command B followed a north path, and Command A, including Jackson’s 25th Engineer Battalion, took a south path, intending to reach the city of Brest, at the extreme tip of the region.17 Brest was a strategic take for the Allied forces. The city had a deepwater port that could receive shipments sent directly from the United States and help reduce the supply bottleneck still running through the Normandy beaches. But while occupying France, the Germans had installed a Navy submarine base in the city, and with 40,000 men stationed in the city, Hitler had declared Brest a fortress to be defended.18

On August 7, Command B of the 6th AD struck the city’s defenses from the northwest but met strong direct-fire resistance. Unfortunately, the other parts of the division, including Jackson’s battalion, encountered bad road conditions and spotty resistance along the way. Their late arrival near Brest gave the German troops extra time to reinforce and improve their defenses. Missing the opportunity to surprise an unprepared enemy, the battle to liberate Best turned into a long and deadly assault that ended only on September 19, 1944.19

On August 12, the Super Sixth received new orders from Allied Command to move southeast to the Lorient and Vannes area of the Brittany Peninsula.20 Jackson’s Company remained in position, containing Brest until elements of the VIII Corps relieved them. On August 17, it relocated again to Arzano, north of Lorient.21 Three days later, Jackson and the 25th Engineer Battalion joined “Task Force Brown,” which comprised both armored and infantry elements led by Lieutenant Colonel Brown. The Army tasked them with capturing the smaller towns and villages in Southern Brittany, including the garrison of Concarneau. They used psychological warfare including sound trucks and the stationing of tanks in and around the town to intimidate the enemy. After liberating Concarneau on August 24, Jackson’s company was attached to the 15th Tank Battalion and moved forty miles east to Caudan, where they fought until September 16.22

Assigned to the XII Army Corps on September 20, 1944, the 6th AD, including Jackson’s Company B of the 25th Engineers Battalion, left Brittany to travel nearly 500 miles east, passing through Orléan to reach Colombey-Les-Belles, twenty miles southwest of Nancy.23 The Allied forces had hoped for a rapid drive through Lorraine, but bad weather, fierce German resistance, and a disastrous logistical situation thwarted their goal and impeded their advance. From September 26 to October 2, 1944, the 6th AD and the 35th Infantry Division, withstood raging combat in the forest of Grémecey, northeast of Nancy, which a section of the Seille River, a tributary of the Moselle River, crossed. Jackson, with his battalion, in immediate support of the front-line units, participated in maintenance programs, placing tracks on vehicles, overhauling motors, and replacing worn parts during this period.24 Furthermore, as a technician for a combat engineer battalion, Jackson rebuilt and maintained roads and equipment, opened new routes for vehicles and equipment, checked and even rebuilt bridges when necessary.25

After such fierce fighting, Jackson’s battalion pulled back in October 1944, continuing to train and do maintenance work in and around Nancy. This included checking bridges, repairing roads, and improving bivouac areas. On November 5, much of Jackson’s battalion attended a Catholic mass in the church of Lay-Saint-Christophe, a last quiet moment before the division began the Saar Campaign on November 8. In anticipation, that morning, the Allied Command briefed Jackson and the rest of the 25th Engineer Battalion that the “big drive” would be to end the war before Christmas. Then, the battalion packed up, marched about five miles north, under rain, and arrived in the village of Leyr within a day. The 25th Engineer Battalion spent the following days repairing bridges and engaging with the enemy in Nomeny, Mailly, Secourt, and Tragny, an area midway between Metz in the north and Nancy in the south.

On November 12, the engineering company, at the start of the day, completed a treadway bridge south of Baudrecourt, after which they moved east with another bridge in sight. When arriving east of the village, they faced heavy artillery and ground fire, unable to move towards the bridge. Suddenly, eight shells landed within five feet of the company commander’s jeep, which Jackson was driving, killing him.26 After traveling with the 6th Armored Division across France, Jackson’s untimely death occurred on November 12, 1944, near the village of Baudrecourt south of the city of Metz in the department of Moselle. The Tampa Bay Times announced his death twenty-one days later.27

Legacy

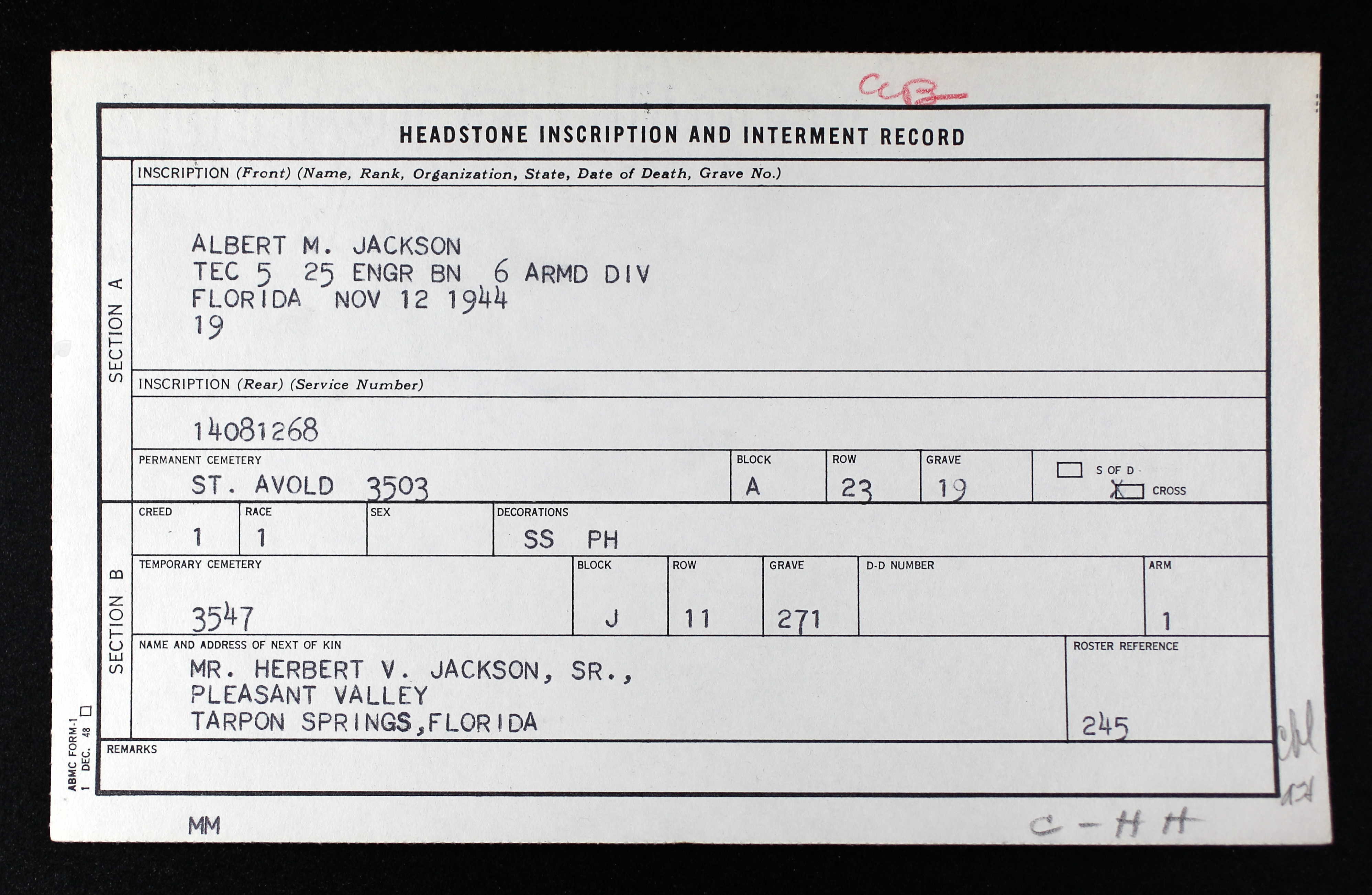

According to Jackson’s headstone inscription and internment record, the United States awarded Albert M. Jackson, in addition to a Purple Heart for the mortal injuries he sustained in combat, a Silver Star. The Silver Star is the US Armed Forces third highest military medal awarded for “gallantry in action.”28

Moving through a devastated country such as war-torn France meant engineers needed to construct infrastructure vital to Allied maneuverability, but it also put them in harm’s way. While we are not sure how Jackson earned it, we know he must have gone beyond what is expected of those in service to earn the Silver Star.

According to the 6th Division’s history, the men of 25th Armored Engineer Battalion were the “most versatile troops of the 6th Armored Division.”29 Throughout its time in France, the battalion constructed fifty-two treadway bridges totaling over 2,070 feet, cleared 110 major roadblocks, repaired 154 major road craters, and swept over 221 miles of road for land mines across France.30 This demonstrates the obstacles the Army regularly faced, which specialized engineer units cleared to keep the Allies moving forward, and gives some insight into how Jackson may have earned the Silver Star.

A monument stands for the 6th Armored Division in Heinerscheid, northern Luxembourg, in honor of the unit’s participation in the Battle of the Bulge.31 In early April 1945, the Division overran the concentration camp at Buchenwald; in 1985, both the US Army’s Center of Military History and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum recognized the Super Sixth as a liberating unit.32

Jackson was survived by his father, Herbert Jackson Sr., and brother, Herbert Jr. Herbert Jackson Sr. lived in Pleasant Valley, Tarpon Springs, FL, until he died in 1955. He was laid to rest alongside his wife Clydia, in Ponceannah Cemetery, Paisley, FL.33 Herbert Jr., who served during World War II, also served in Korea, becoming a Sergeant in the US Army.34 He lived until 1998 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.35 Albert McKnight Jackson is buried in the Lorraine American Cemetery in St. Avold, France, where he can forever rest in peace.36

1 “1920 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Albert Jackson, Altoona, Lake, Florida; “U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Albert M. Jackson, 2203.

2 “1910 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Herbert Vernon Jackson, Precinct 19, Orange, Florida; “Herbert Vernon Jackson Jr.,” Find a Grave, accessed October 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49235777/herbert-vernon-jackson.

3 “1900 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed November, 2022), Albert Keith; “1880 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed November, 2022), Herbert Jackson; “U.S., WWI Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Herbert Vernon Jackson; “1880 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Herbert Vernon Jackson, District 321, Baldwin, Georgia; “1920 U.S. Census.”

4“1910 U.S Census.”

5 Scott Hussey, “Freezes, Fights, and Fancy: The Formation of Agricultural Cooperatives in the Florida Citrus Industry,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 89, no. 1 (2010): 82-83.

6 “U.S., WWI Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Herbert Vernon Jackson, 297.”

7 “U.S., WWI Registration Card;” “World War I Draft: Topics in Chronicling America,” Library of Congress, accessed April, 2024, https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-wwi-draft.

8 “Clydia K Jackson, Find a Grave, accessed October, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/101621318/clydia-k-jackson.

9 “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Albert Jackson, Pinellas, Florida; “1935 Florida State Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May, 2024), Albert Jackson, Dixie County, Florida; Jeffrey Drobney, “Company Towns, and Social Transformation in the North Florida Timber Industry, 1880-1930,” Florida Historical Quarterly 75, no. 2, 121-122, 145.

10 “1940 U.S. Census.”

11 “Produce Clerk Miles Orr First District 1 Draftee,” Tampa Bay Times, December 5, 1940; “First Draftees Will Get Rousing Senoff Here,” Tampa Bay Times, December 5, 1940.

12 “1940 U.S. Census;”“U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Hebert Jackson.

13 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,”database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Albert Jackson, 14081268; “1940 U.S. Census;” “U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Albert M. Jackson.

14 Cressman, George E. “Camp Blanding in World War II: The Early Years.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 97, no. 1 (2018): 35–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45210098.

15 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), entry for Albert Jackson, service number 14081268.

16 United States Army, Combat History of the 6th Armored Division (Washington: William E. Rutledge, 1946), 6-7. (https://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/41/ accessed June 28, 2024).

17 Combat History of the 6th Armored Division, 15-20, 63.

18 Ed Lengel“ Forgotten Fights : Assault on Brest, August-September 1944,” The National WWII Museum, September 21, 2020, accessed April 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/fortress-brest-assualt-1944.

19 Combat History of the 6th Armored Division, 65-73; Lengel“ Forgotten Fights : Assault on Brest, August-September 1944.”

20 Combat History of the 6th Armored Division, 65-71.

21 “Company B, 25th Armored Engineer Battalion Unit History,” Super Sixth : The Story of Patton’s 6th Armored Division in WWII, 2, accessed October 2023, http://www.super6th.org/25th_eng/index.html; Combat History of the 6th Armored Division, 73-76. The history of Company B appears on Super6th.org thanks to a family member who typed the manuscript at the National Archives.

22 Combat History of the 6th Armored Division, 23-23; “Company B, 25th Armored Engineer Battalion Unit History,” 2-5.

23 “Company B, 25th Armored Engineer Battalion Unit History,” 5.

24 Combat History of the 6th Armored Division, 23; “Company B, 25th Armored Engineer Battalion Unit History,”5-6.

25 Eugene Reybold. “The Role of American Engineers in World War II.” The Military Engineer 37, no. 232 (1945): 39–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44559575; “Company B, 25th Armored Engineer Battalion Unit History,”5-7.

26 “Company B, 25th Armored Engineer Battalion Unit History,” 8-16.

27 “Cpl. A. Jackson Killed in Action.” Tampa Bay Times. December 3, 1944; “U.S., WWII Hospital Admission Card Files,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October, 2022), Albert Jackson, 14081268.

28 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records,” US Department of Defense, “Description of Medals,” accessed June 28, 2024 https://valor.defense.gov/description-of-awards/.

29 Combat History of the 6th Armored Division, 173.

30 Combat History of the 6th Armored Division, 174.

31 “6th Armored Division,”American War Memorials Overseas Inc., accessed November 29, 2022, https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=721&MemID=1011

32 “The 6th Armored Division during World War II,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed November 20, 2022, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-6th-armored-division.

33 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records;” “Clydia K Jackson,” Find a Grave, accessed November, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/101621318/clydia_k_jackson.

34 “Herbert Vernon Jackson Jr., Find a Grave, accessed October, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/49235777/herbert-vernon-jackson.

35 “Herbert V Jackson, Find a Grave, accessed October, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/101621306/herbert-vernon-jackson.

36 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed October 2022), Albert M. Jackson, 14081268.