Tec 5th William Harris Jr. (September 7, 1909 – December 26, 1944)

3908th Quartermaster Truck Company

by Emily Sleezer

Early Life

William Harris Jr. was born on September 7, 1909 to William and Josephine Harris in Titusville, FL.1 William and Josephine had seven children: Roderick (1898), Belle (1899), Minerva (1901), Jessie J. (1903), Laura (1905), Samuel (1908) and William Jr. (1909).2 William Harris Sr. initially worked as a laborer but must have gained enough experience to become a carpenter, possibly specializing in either home repairs or construction.3 He may have had a private workshop within his home, worked in other people’s homes, or worked constructing houses.

Whatever kind of carpentry William Harris Sr. did, it is likely that he participated in the construction that accompanied Florida’s land boom. In 1920, more than sixty percent of the population in Florida lived on small farms or in small towns, but by 1930 over fifty percent of the population lived in or moved to towns of at least 2,500 persons.4 The Harris family worked hard and overcame structural discrimination to earn enough income to not only own a home, but to be free of a mortgage, as indicated in the 1920 US census, seen here.5 Harris Sr. may have had financial help from his mother or eldest brother, Roderick, as it was still no small feat for an African American family to own their own home outright in the early twentieth century.

While the details of Harris Jr. and his six siblings’ adolescent years are unclear, they all likely attended a segregated grammar school then either started to work or married to start their own families. Harris Jr.’s enlistment record shows he completed grammar school, so it is likely that his other siblings attended as well. His oldest sister did not appear on later census records, indicating she had moved out, possibly to start her own family.6 Harris Jr. followed suit shortly after his sister, and lived with his first wife in Fort Lauderdale, until filing for divorce in 1941.7 It seems they split up before their divorce, as William worked up to sixty hours a week as a wholesale truck driver in the grocery industry and lived as a lodger in someone else’s home in Tampa, FL in 1940.8

Harris Jr. may have met his second wife Jessie Mae, a cook in St. Augustine, FL, by delivering groceries to the restaurant in which she was employed.9 Harris Jr. and Jessie Mae married on October 21, 1943, in St. Johns County, FL.10 The couple resided in the Lincolnville neighborhood of St. Augustine, which was established in 1866 as the black section of the nation’s oldest and “most segregated” city.11 Lincolnville was home to many activists whose protests eventually led to the end of St. Augustine’s segregation during the Civil Rights Era.

Military Service

In September 1940, Congress passed the Selective Training and Service Act which, in addition to readying the nation for war, officially prohibited racial discrimination in the draft.12 All men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-six began to register for the draft, with Harris Jr. completing his registration in October 1940.13 The US Army called Harris Jr. to enter the service in April 1942, only a few months after the US declared war.14 Harris was the exception; many African Americans were not drafted until 1943 because, despite the prohibition of discrimination in the military, it occurred in practice. African Americans in the Army were often, “little more than ‘servants in khakis’ under the leadership of white officers.”15 In civilian and military life, they were subject to segregation that was most certainly not “separate but equal.” African American soldiers often received the most menial, low-grade tasks such as cooking, driving trucks, caring for horses, and custodial duties. Their military authorities also confined these soldiers to billet in the least desirable parts of the training camps, where they lacked proper resources and facilities.16

Before the Pearl Harbor attack, most Americans wanted to remain isolated from the conflict in Europe. Such a devastating attack, However, called the US to action. Many in the African American community felt torn about the war, meeting it with both hope and cynicism. They viewed it as a “white man’s war,” but also recognized it as a means to further their fight to disrupt the status quo of segregation and discrimination in the country.17 This led to the creation of the “Double V” campaign, backed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the black press, and A. Philip Randolph, the president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.18 Through civil rights groups dedicated to the “double victory” – freedom and democracy abroad and at home – African Americans fought discrimination in the military and in the workforce, ultimately laying the groundwork for the modern Civil Rights Movement.19

Once drafted, Harris Jr. trained at Camp Blanding, located near Jacksonville, FL. Over 800,000 men trained in this camp between 1940 to 1945.20 Of the more than 920,000 African Americans that served in World War II, eighty percent received their training in the south, with several bases located in Florida.21 While many African American soldiers could not rise above the rank of private, Harris Jr. became a Technician 5th Grade, likely due to his time and experience as a wholesale grocery truck driver.22 After World War I, the US Army simplified rank designations into a seven-tier pay grade with the creation of technician grades 3 to 5. Technician grades, or ranks, were created as a way to provide additional pay to soldiers who had extra skills or experience but did not have the leadership roles of a traditional noncommissioned officer rank, such as corporal or sergeant.23 Harris Jr. worked in the 3908th Quartermaster Truck Company unit which was responsible for mechanical repairs, and, most importantly, for transporting cargo and equipment to the deployed US forces.24

In March 1944, the US Army stationed Harris Jr. and the 3908th Quartermaster Truck Company at the town of Biddulph located in Staffordshire, England, where they supplied the US troops stationed in England prior to the D-day invasions of France.25 We know his unit eventually shifted to France, and possibly worked on the Red Ball Expressway, a treacherous 700-mile inland truck convoy route from St. Lô, France to American divisions that were pursuing the retreating German forces across France and into Germany. For this expressway, the Army pulled personnel from the Quartermaster Corps, which included a significant percentage of the African Americans serving in the Army.26

Legacy

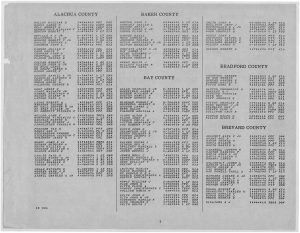

Tech 5th Grade William Harris Jr. died in France on December 26, 1944, at the age of thirty-five.27 The field hospital recorded his death as a “battle casualty” from a bullet wound in the leg received “in line of duty.”28 Despite this, the World War II Army Casualty Listing, seen here, counted Harris Jr. as “DNB,” or “died non-battle,” which may explain why he did not receive a Purple Heart, the standard decoration for injury or death in the line of duty.29 His death came only ten days after the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge, a major German counter-offensive that lasted from December 16, 1944 to January 25, 1945. It is not certain whether his death was connected to the fighting in the Ardennes Forest, but there is a good chance he died while trying to supply front line troops during this chaotic period.

William Harris Jr. was killed in the line of duty, which raises important questions about why he was denied a Purple Heart for his ultimate sacrifice while serving overseas. Did the Army deny him this honor because he was African American who did not serve in a combat unit? His fellow soldiers buried him in a temporary cemetery, probably near the hospital where he died, and, after the war ended, the US Army reinterred Harris Jr. at the Lorraine American Cemetery in Saint-Avold, France – Plot C, Row 14, Grave 36.30 His wife, Jessie Mae, remained in their home in the neighborhood of Lincolnville and continued to work in restaurants after his passing.31

1 “WWII Army Enlistment Records,” database, fold3.com, (https://www.fold3.com: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for William Harris Jr., Army Serial Number 34203367; This enlistment record has 1909 listed as William Harris Jr.’s year of birth, but there are slight discrepancies related to his birth with other sources. His registration card has his birth year listed as 1910, but this document also appears to have possibly been filled out by someone other than William, which may be the cause of this error. We used 1909 in this biography as we have more documents with this date.

2 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for William Harris Jr., Brevard, Titusville, Florida.

3 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for William Harris, Brevard, Titusville, Florida; “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for William Harris, Brevard, Titusville, Florida.

4 Nick Wynne and Richard Moorhead, Florida in World War II: Floating Fortress (Charleston: History Press, 2010), 18.

5 “1910 United States Federal Census,” entry for Josephine Harris, Brevard, Titusville, Florida; “1920 United States Federal Census,” entry for Roderick Harris, Brevard, Titusville, Florida.

6 “WWII Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com, (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2021), William Harris Jr.; “1910 United States Federal Census,” entry for Belle Harris, Brevard, Titusville, Florida; “1920 United States Federal Census,” entry for William Harris, Brevard, Titusville, Florida.

7 “Divorce Suits Are Filed Here Today,” Fort Lauderdale News, March 28, 1941, Newspapers.com

8 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for William Harris, Hillsborough, Tampa, Florida; Despite the absence of “Jr.” in this census record, based on the surrounding evidence it is likely that this William Harris is the veteran in question for this biography. Other official records, such as his marriage and Army hospital records, also omit the “Jr.” in his name. As this is a census record filled out by a non-family member head of household, they may have not known he has “Jr.” at the end of his name, or may have not thought to put it on the census.

9 “Ohio and Florida, U.S., City Directories, 1945,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for Wm jr (c; Jessie).

10 “Florida, County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Acnestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for William Harris.

11 “Florida: Lincolnville Historic District,” National Park Service, accessed March 21, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/places/florida-lincolnville-historic-district.htm.

12 Wynne and Moorhead, Florida in World War II, 15.

13 “WWII Registration Card.”

14 “WWII Army Enlistment Records.”

15 Jon Evans, “The Origins of Tallahassee’s Racial Disturbance Plan: Segregation, Racial Tensions and Violence During World War II,” Florida Historical Quarterly 79, no. 3 (Winter 2001): 349.

16 Ibid, 346-364.

17 Richard M. Dalfiume, “The ‘Forgotten Years’ of the Negro Revolution,” The Journal of American History 55, no. 2 (June 1968): 90-106.

18 Evans, “The Origins of Tallahassee’s Racial Disturbance Plan,” 346-364.

19 Andrew Kersten, “African Americans and World War II,” OAH Magazine of History 16, no. 3 (Spring 2002): 13 – 17.

20 Allan McCollum, A History of Camp Blanding, pamphlet, (Tampa: Camp Blanding Museum and Memorial Park, n.d.).

21 Evans, “The Origins of Tallahassee’s Racial Disturbance Plan,” 346-364.

22 “William Harris Jr.,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed March 21, 2021, https://abmc.gov/decedent-search/harris%3Dwilliam-11.

23 “A Visual Guide To: U.S. Army Rank Insignia, World War II,” Veterans Voices, accessed March 21, 2021, https://veteran-voices.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/wwii-us-army-rank-insignia.pdf.

24 War Department Field Manual, Quartermaster Truck Companies, FM 10-35 (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1945).

25 Phil Grinton, “Black Army,” Lest We Forget, accessed April 5, 2021, http://lestweforget.hamptonu.edu/page.cfm?uuid=9FEC33CE-A2CF-1F18-17BB80C36E759D20.

26 M. Todd Hunter, “Black History Month 2015: Remembering the Red Ball Express,” DAV, February 19, 2015, (https://www.dav.org/learn-more/news/2015/black-history-month-2015-remembering-red-ball-express/: accessed April 5, 2021).

27 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Record,” database, Ancestry.com, (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for William Harris Jr.

28 “U.S. WWII Hospital Admissions Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Fold3.com, (https://www.fold3.com/: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for William Harris.

29 “World War II Honor List of Dead and Missing,” database, Fold3.com, (https://www.fold3.com/: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for William Harris Jr.

30 “William Harris Jr..”

31 “St. Augustine, Florida, City Directory, 1955,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2021), entry for Jessie M (wid Wm).