Sgt. John B. Hancock (November 30, 1913 – November 1, 1944)

179th Infantry Regiment (the “Tomahawks”), 45th Infantry Division

by Christian Bates and Elizabeth Klements

Early Life

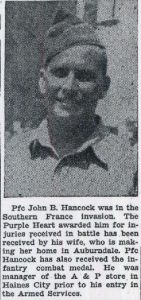

John Blackshear Hancock was born on November 30, 1913, in Boston, Georgia, to Mamie and John Hancock Sr.1 The Hancocks had seven children: Tecoy (1900), Lillie (1902), James (1905), twins Virgil and Vivian (1909), John Jr. (1913), and Emily (1920).2 At first, they lived and worked on a farm in Thomas County, Georgia. In 1916, Lillie passed away, and, sometime in the 1920s, the rest of the family moved to Auburndale, Florida.3 By 1930, Tecoy and James had married and set up their own households in Auburndale, while the parents and the younger children worked in the citrus industry. Hancock Sr. was a fruit picker, while his wife Mamie worked in a canning plant. Virgil transported the produce, and both Vivian and John Jr. worked in the fruit packing house.4 In 1932, John Hancock Sr. passed away.5 A few years later, in 1937, Hancock Jr. married Edna Pearl McGinnis.6 By 1943, he was working as a manager at an A & P Store in Haines City, Florida. He was also an active member of the local Baptist church.7

Military Service

The US government requested Hancock to appear for a physical examination in mid-November of 1942.8 A couple months later, on May 11, 1943, he reported for military training and service at Camp Blanding, Florida.9 Hancock trained at Macon, Georgia, during which he was allowed to take a couple weekends off to visit his wife in Florida.10 After training, he was assigned to the 179th Infantry Regiment in the 45th Infantry Division.11 The 45th was originally a National Guard division; one of four activated by President Roosevelt in 1940 and assigned to active service once the war began. Other servicemen nicknamed Hancock’s 179th Regiment the “Tomahawks,” due to a distinct patch – a blue coat of arms with white, crossed tomahawks – that the men in the division wore.12

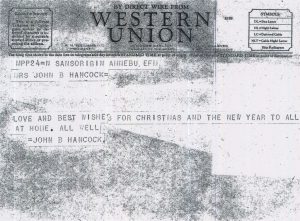

The US Army first sent the 45th Division to North Africa to prepare for the liberation of Italy. It arrived in Morocco in June, 1943, and began to launch attacks on the Italian coastline in July.13 Hancock arrived in North Africa a little later than the rest of the division, on Thanksgiving Day, 1943.14 The 45th landed in Sicily in July and began working its way up the Italian peninsula. When Hancock arrived, they were in the middle of a campaign to take the Naples area, which lasted from September 1943 to January 1944.15 It is not clear if Hancock participated in this campaign. In December, he sent two telegrams to Edna: one saying he was safe and that she should not worry, and then one saying Merry Christmas and Happy New Year.16

After taking the Naples area, the Allied forces set their sights on Rome. On January 22, 1944, the 45th Division landed at Anzio, a coastal city about thirty-two miles south of Rome, and began a four-month push across those thirty-two miles against fierce Axis resistance.17 Early in the campaign, in February, artillery shells struck Hancock on the thigh during a battle. The medics took him to a hospital where he remained for about a month. He then returned to service, having received a Purple Heart for injuries in the line of duty.18 The Anzio Campaign ended successfully with the capture of Rome on June 5, 1944.19

Hancock often wrote to his wife when he could, sending her day-to-day accounts of his life in the service. He described lots of marching, with interspersed accounts of who died in battle that day as well as where church was held that Sunday. In addition, he sent Edna and his mother photos and souvenirs from his time in North Africa and Italy, including postcards, examples of German, French Algerian, and Italian currency, and a confiscated letter of safe conduct that German soldiers presented when they surrendered.20

After the capture of Rome, the 45th paused to rest and to train in Italy. In August 1944, the US military leaders ordered the 45th to assist in Operation Dragoon, the Allied liberation of Southern France. The division landed at St. Maxime, on the southern coast, on August 15, 1944, and began to push north and east toward Germany, liberating town by town. By October, it reached the foothills of the Vosges mountains which lay on the French-German border.21 On November 1, as the division pushed through the forests near Mortagne, France, Hancock went missing in action.22 The day before, on October 31, he had written home saying he had made the rank of corporal.23

Legacy

Although Hancock went missing in action in November 1944, the army did not recover his body and declare him killed in action until April 1945.24 They buried him at the Epinal American Cemetery in France. For his sacrifice, the Army awarded him an Oak Leaf Cluster to add to his Purple Heart. Hancock had also earned a Good Conduct Award and an Infantry Combat Medal at the time of his death.25

When the Army declared Hancock dead, both Hancock’s army chaplain and a lieutenant from his 179th regiment sent letters of condolence to Edna. The latter wrote that “his loss has been felt keenly in this regiment, as he was an excellent soldier and was admired by all who knew him.”26 The chaplain assured Edna that “John was given a military funeral and was buried by a Chaplain of his faith in a beautiful American cemetery.”27

The local papers also published frequent articles about Hancock throughout his military service, announcing his wounds in Italy, the awards he received, and more. These articles ended in May 1945, with his obituary.28 Hancock’s loved ones held a memorial service for him on September 2, 1945, in the Baptist church that he attended before the war.29

1 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May 18, 2021), entry for John B. Hancock.

2 “1910 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May 18, 2021), entry for John Hancock; “1920 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May 18, 2021), entry for John Hancock.

3 “1920 U.S. Census;” “1930 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May 18, 2021), entry for John Hancock; for Lillie’s death see “Lillie May Hancock,” Find a Grave (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/167886166/lillie-mae-hancock: accessed May 18, 2021).

4 “1930 U.S. Census,” entry for John Hancock; entry for Tecoy Mims; entry for James Hancock.

5 “Florida Death Index,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May 18, 2021), entry for John B. Hancock (Sr.).

6 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1923-1982,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May 18, 2021), entry for John Blackshear Hancock and Edna Pearl McGinnis.

7 “Killed in Action,” newspaper article provided by Linda Hughes, see image at the RICHES Epinal American Cemetery Collection here. Special thanks goes out to Linda S. Hughes for reaching out to Dr. Lyons and sending pictures of her scrapbook containing lots of personal records of John Hancock and letters that he sent during the war. All documents were approved for usage and all credit is due to Linda for sending us this great glimpse at Sgt. Hancock’s life.

8 Dr. D.H. Rogers, Clerk of the Local Board. Notice To Registrant to Appear for Physical Examination. Haines City, Fl, Nov. 19, 1942. Courtesy of Linda Hughes.

9 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May 14, 2021), entry for John B. Hancock.

10 Company Commander, Enlisted Man’s Pass. Macon, Georgia, July 1943.

11 “U.S., Headstone Inscription and Internment Record,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May 14, 2021), entry for John B. Hancock.

12 “History of the 45th Infantry,” The 45th Infantry Thunderbird Museum, http://45thdivisionmuseum.com/index.php/history/history-of-the-45th-infantry/: accessed May 14, 2021.

13 U.S. Army, “45th Infantry Division – Thunderbird,” US Army Divisions, https://www.armydivs.com/45th-infantry-division: accessed May 14, 2021.

14 “Killed in Action.”

15 U.S. Army, “45th Infantry Division.”

16 Personal telegrams from Sgt. John B Hancock to Edna P. Hancock. Direct wire from Western Union, December 1943. Courtesy of Linda Hughes. See images at the RICHES Epinal American Cemetery collection here and here.

17 U.S. Army, “45th Infantry Division.”

18 “U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed May 14, 2021), entry for John B. Hancock; “Auburndale Man Killed in Action,” newspaper article, courtesy of Linda Hughes.

19 U.S. Army, “45th Infantry Division.”

20 Various letters, photographs, and items, sent by John Hancock through the Army Postal Service, ca. 1944. Courtesy of Linda Hughes. See images at the RICHES Epinal American Cemetery: postcards, Italian currency, French Algerian currency, German currency, safe conduct pass.

21 U.S. Army, “45th Infantry Division.”

22 Warren P. Munsell, The Story of a Regiment: a History of the 179th Regimental Combat (U.S. Army, 1946), 93 – 94.

23 “Dear Boys,” newspaper article, courtesy of Linda Hughes. See image at RICHES Epinal American Cemetery here.

24 Letter from John R. Hull to Edna P. Hancock, April 23, 1945. Courtesy of Linda Hughes. See image at RICHES Epinal American Cemetery here.

25 “Headstone and Internment Records;” “Killed in Action.”

26 Letter from John R. Hull.

27 Letter from Kenneth E. Metcalf to Edna P. Hancock, May 3, 1945. Courtesy of Linda Hughes. See image at RICHES Epinal American Cemetery Collection here.

28 “Killed in Action;” “Auburndale Man Killed in Action.”

29 Memorial services program for Sgt. Hancock, courtesy of Linda Hughes. See image at RICHES Epinal American Cemetery Collection here.