Pvt. Daniel J. Fernandez (August 2, 1923 – September 16, 1944)

318th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Division,

by Brendan Jordan

Early Life

Daniel Jesus Fernandez was born on August 2, 1923, in Key West, FL.1 He grew up with his parents, Jose Fernandez and Evangelina Fernandez, and his older brother, Delfin Ramon (1920). Jose and Evangelina were both the children of Cuban immigrants who likely arrived in the US during the political strife that engulfed Cuba in the latter half of the nineteenth century.2 Born in Key West in 1895, Jose Fernandez and his four siblings grew up in the city. His father worked in the cigar business, which Jose began working in as early as 1920.3 Evangelina Fernandez, also born in Key West in 1895 to a Cuban cigarmaking family, grew up alongside her sister Carmen.4 Before the birth of their children, Jose and Evangelina lived with Jose’s family. Jose worked as a cigar maker alongside his father, a booming industry that employed members of a growing Cuban-American community living in the Keys.5 Jose and Evangelina eventually rented a home together on Duval Street after the birth of their two sons, Daniel and Delfin. According to the 1930 census, Evangelina’s mother, Modesta Hernandez, also lived with the budding family as well as a lodger, who likely supplemented the family’s income.6

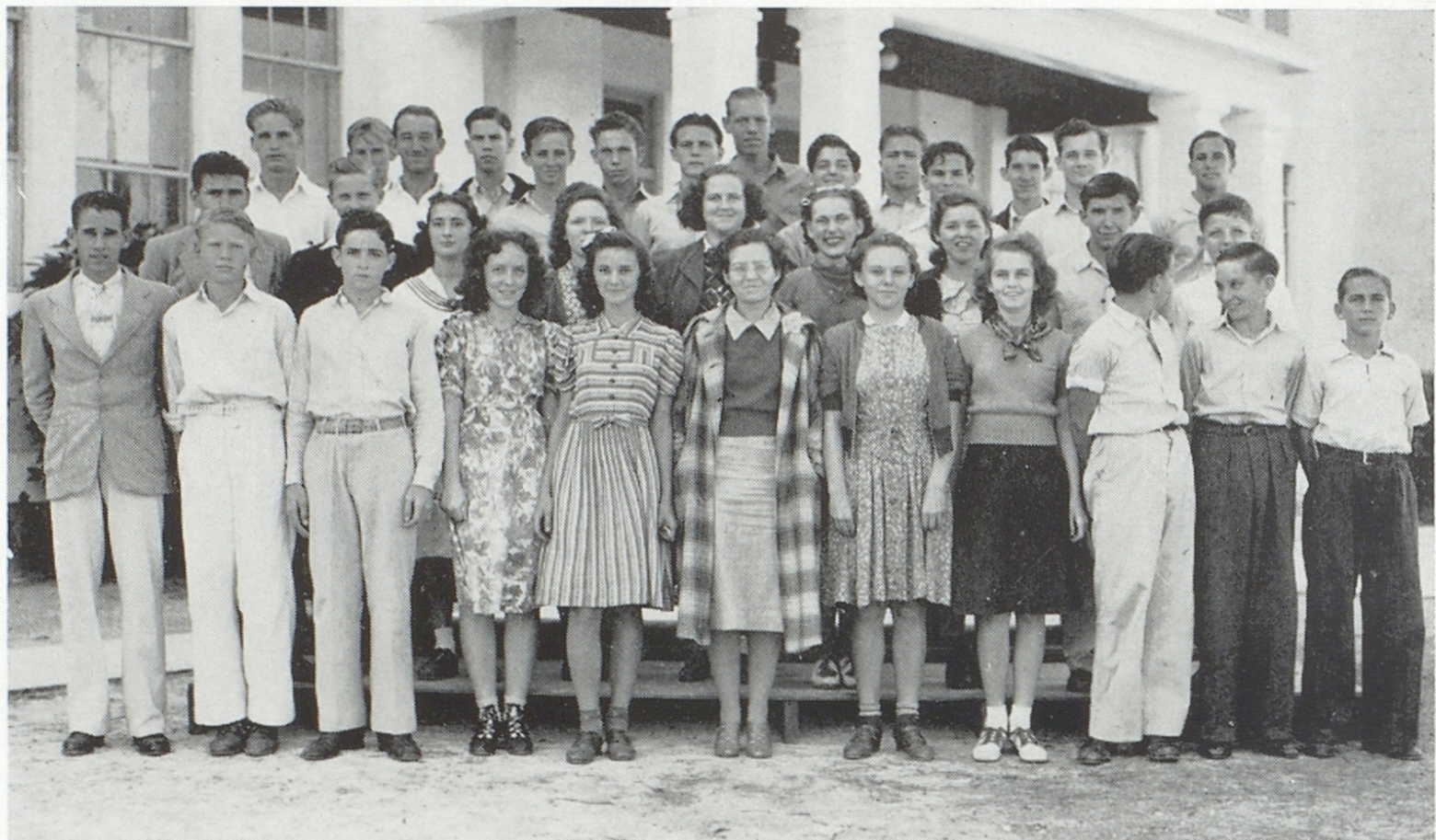

Living in Key West enabled the Fernandez family to remain close to their relatives in Cuba. As a result, they traveled extensively between the US and Cuba. This could demonstrate a closeness between Daniel Fernandez and the rest of his extended Cuban family.7 Daniel attended Key West High School for at least two years; he appears in this freshman class group photo. Daniel’s older brother by three years, Delfin, likely left school after seventh grade to enter the workforce, assisting his family during the Great Depression.8 Like most cities in the US, the economic situation in the 1930s hit the tiny island of Key West extraordinarily hard. It resulted in millions of dollars of debt, non-existent city services, and eighty percent of the population receiving government welfare benefits of one type or another. Decades earlier, economic reports considered Key West the wealthiest city in the US per capita; however, during the 1930s, the average family made only seven dollars a month.9

Aside from school, Daniel worked at the Stand Theater on Duval Street as a “semi-skilled motion picture projectionist,” a new and exciting profession for anyone in the early years of cinema.10 Sometime before 1940, his parents moved out of the cigar industry, a common trend among cigar makers in Key West as the industry began relocating to Tampa. For many, the Great Depression became the final nail in the coffin for the once-booming cigar industry in Key West.11 Jose and Evangelina worked as clerks in a grocery store, while their son, Delfin, worked as a caretaker at an aquarium. Daniel most likely continued working as a motion picture projectionist until his enlistment in the US military.12

Military Service

Daniel registered for the draft at eighteen years old on June 30, 1942.13 His older brother, Delfin, enlisted into the Army on September 18, 1942; Daniel joined the Army on February 26, 1943.14 The US Army processed Daniel through Camp Blanding in Starke, FL, approximately thirty-one miles southwest of downtown Jacksonville. Daniel likely received basic training there due to the construction of additional infrastructure to the base, enabling it to become an Infantry ReplacementTraining Center (IRTC). Fernandez transferred to Camp Phillips in Saline County, KS, for further training after joining the 318th Infantry Regiment of the 80th Infantry Division (ID). With the 318th, Fernandez engaged in additional drilling at the California-Arizona Maneuver Area in the Mojave Desert. The Army initially designed the training ground to prepare soldiers for North African environments but, as the war progressed, expanded it to accommodate the environments in Italy and France. While at the Mojave grounds, the soldiers of the 318th found the extremely high temperatures and sandy conditions much more intense than any training they had received before.15 Throughout his time training, Daniel visited medical facilities on three separate occasions due to illness.16

On July 4, 1944, the 318th Infantry Regiment sailed out of New York Harbor on the RMS Queen Mary towards Gourock, Firth of Clyde, Scotland. From there, they traveled to Norwich, England. The unit spent the remainder of July training to fight in France. Specifically, they focused on the physical environment of Normandy, including its beaches and cliffs as well as the agricultural areas up to fifty-sixty miles inland.17

In early August, just two months after the initial D-Day landings, Daniel, part of K Company, crossed the English Channel in a barge and landed on Utah Beach.18 Assigned to the XX Corps of Patton’s Third Army, the 80th ID immediately moved to support Allied forces further inland after successive victories in the cities of Cherbourg and Caen. Following these battles, Allied forces rushed to capture the French town of Avranches, sixty miles south of Utah Beach in the southern part of Normandy. After capturing the city of Avranches on July 31, 1944, German forces began retreating East across the region.19 Resistance from the German Army, in addition to the thousands of French refugees that lined the roads of France, impacted the Allied advance further into the country. Allied forces saw an opportunity to encircle the retreating German Army and cut off any possible counterattack. On August 8, the US and its allies, including the 80th ID, collectively fought a series of battles in the area known as the Falaise Pocket, south of Caen. The Allies trapped retreating Germans in and around Falaise, a small town in Normandy approximately sixty miles east of Avranches, on August 21. They encircled and captured around 50,000 German soldiers, which allowed the Allies to continue their planned push east across France with reduced resistance from the German army.20

Following the Allied success in and around Falaise, Daniel and the rest of the 318th Infantry Regiment rested in Médavy, a town twenty miles south of Falaise, until August 25, when the Army ordered the regiment to move hastily to the French town of Collemiers, about seventy miles south west of Paris. The 318th traveled hundreds of miles in one day, reaching Collemiers at 1:30 am on August 26. Immediately after sunrise, the regiment moved forty miles northeast to Vallant-Saint-Georges, a town along the western bank of the Seine River. Over two days, August 27-28, Daniel and the 318th traveled another sixty miles, crossing the Seine, Aube, and Marne rivers and encountering their first significant German resistance in a week when crossing the Marne. Following the successful crossing of the Marne, they traveled northeast to Les Grande-Loges. The 318th and the rest of the 80th ID immediately traveled another forty-five miles southeast to Bar-Le-Duc. The division remained stationed within the vicinity of Bar-Le-Duc to secure and guard the area while other Allied units moved ahead to cross the Meuse River. Starting on September 1, Daniel and the 318th traveled through several communes relatively untouched, such as Saizerais and Rosières-en-Haye. On September 12, under darkness, the 318th crossed the Moselle River in the early morning hours and entered the vicinity of Ville-au-Val, six miles south of Pont-à-Mousson, where they met heavy German opposition. The hills in the area provided the Germans with the high ground, which made the objective of taking territory incredibly difficult. The repeated German counterattacks slowed the 80th ID as it pushed through this region.21 The battles surrounding Butte de Mousson, in particular, took a significant toll on the men of the 318th. From September 13-16, Daniel and his division endured brutal fighting, with territory switching sides multiple times throughout the skirmishes.22

On the morning of September 16, 1944, the 318th Infantry Regiment received orders to participate in a surprise attack on Sainte Geneviève Hill.23 Hiding within a cave, a group of German soldiers attacked the men of Company K with a barrage of grenades. The US Army determined that Daniel and four others died instantly in the series of explosions.24 Even though men in his regiment knew of his death, the Army listed him as missing in action (MIA), its policy when a soldier’s remains were not recovered in the heat of battle. Only two days later, on September 18, 1944, the Army changed Daniel Jesus Fernandez’s status to killed in action (KIA) after confirming the grim reality of the attack. The US Army never recovered Daniel’s remains.25

Legacy

After Daniel’s death, the 318th Infantry Regiment pushed forward, fighting at the Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive in the Ardennes forest on the border of France, Belgium, and Germany in December 1944. It also participated in the liberation of two infamous concentration camps deep in German-annexed Austria, Buchenwald in April 1945 and Ebensee in May 1945.26 The US Holocaust Museum and Memorial recognizes the 80th ID as a liberating unit.27 Several towns in Europe have memorials to the sacrifices of the 80th ID, including a plaque commemorating the 80th ID which sits in the center of Pont-à-Mousson, honoring the men who liberated the city in 1944.28

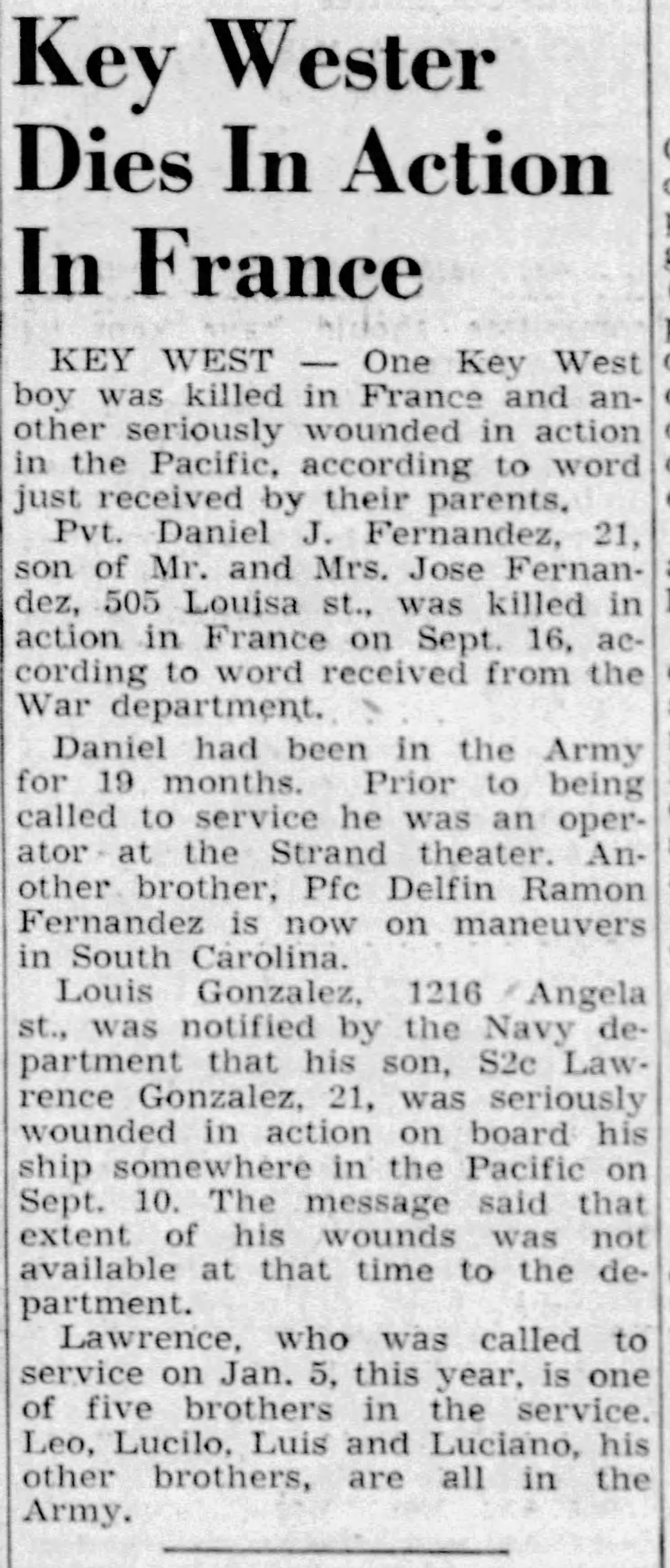

Daniel’s family back home in Key West learned of his death sometime before the end of September 1944. The Miami Herald commemorated Daniel in an article, found here, in October.29

Daniel’s unit suffered more casualties in September 1944 than in any other month due to the brutal fighting they faced as the Germans attempted to hold the defensive line at the German border. According to divisional history, the 80th ID suffered 569 dead, 2,397 wounded, and 685 missing in September alone.30

The US Army posthumously awarded Daniel a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart.While we do not know exactly when or why Daniel earned his Bronze Star, we know he earned a Purple Heart for the mortal injuries he suffered in the line of duty on September 16, 1944.31 Both his parents and his brother survived Daniel. His father died from cancer in 1949, and his mother remained in Key West until her passing in 1978.32 His brother, Delfín, eventually moved to North Carolina sometime after 1950, possibly due to the connections he built while serving in the Carolinas during the latter half of the war.33 Private Daniel J. Fernandez is memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing in the Lorraine American Cemetery and Memorial, alongside 443 other individuals whose resting place is known only to God.34

1 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com: accessed 12 November, 2022), entry for Daniel Jesus Fernandez, serial number N219.

2 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com: accessed 1 November, 2022), entry for Daniel Fernandez, Key West, Monroe Country, Florida; Poyo, Gerald E. “The Cuban Experience in the United States, 1865-1940: Migration, Community, and Identity.” Cuban Studies 21 (1991): 19-36. Accessed 12 October, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24485700.

3 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed 12 October, 2022), entry for Jose Fernandez, Key West, Monroe County, Florida.

4 “1900 United States Federal Census,”database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed 12 October, 2022), entry for Evanjalina Fernandies, Key West, Monroe Country, Florida

5 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed 12 October, 2022); Pozzetta, George E. and Mormino, Gary R. “The Reader and the Worker: “‘Los Lectores’ and the Culture of Cigarmaking in Cuba and Florida.” International Labor and Working-Class History 54 (1998): 1-18. Accessed 3 November, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27672498.

6 “1930 United States Federal Census.”

7 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com. (www.ancestry.com: accessed 3 November, 2022), entry for Daniel Jesus Fernandez, Key West, Monroe Country, Florida; “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed 3 November, 2022), entry for Delfin Fernandez, Key West, Monroe County, Florida; “Florida, U.S., Arriving and Departing Passenger and Crew Lists, 1898-1963,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed 3 November, 2022), entry for Daniel Jesus Fernandez.

8 “U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-2016,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed 28 October, 2022), entry for Daniel Fernandez; “1940 United States Federal Census.”

9 Garry Boulard, “‘State of Emergency’: Key West in the Great Depression,” Florida Historical Quarterly 67, no. 2 (1988): 166-169.

10 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947;” “Electronic Army Serial Number Merged File, ca. 1938 – 1946 (Enlistment Records),” database, The National Archives, access to Archival Database (https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=2&tf=F&q=Daniel+J.+Fernandez&bc=&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=4953523&rlst=2981803,4953523), entry for Daniel J. Fernandez, service number 34546292.

11 Boulard, “‘State of Emergency’: Key West in the Great Depression,” 169.

12 “1940 United States Federal Census.”; “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com: accessed 28 October, 2022), entry for Delfin Ramon Fernandez, serial number 473; “Electronic Army Serial Number Merged File, ca. 1938 – 1946 (Enlistment Records).”

13 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” entry for Daniel Jesus Fernandez.

14 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com: accessed 28 October, 2022), entry for Delfin Ramon Fernandez, serial number 473; “Electronic Army Serial Number Merged File, ca. 1938 – 1946 (Enlistment Records).”

15 “American Battle Monuments Commission,” database, Fold3.com (www.fold3.com: accessed 13 October, 2022), entry for Daniel J. Fernandez; “History of the 80th Division,” database, 80thdivision.com (80thdivision.com: accessed 25 October, 2022); “Camp Blanding Joint Training Area,” Florida National Guard, accessed 12 March, 2024, https://fl.ng.mil/Commands/Camp-Blanding-Joint-Training-Center/#:~:text=It%20was%20subsequently%20enlarged%20to,troops%20trained%20at%20Camp%20Blanding; Andrew Z. Adkins Jr & Andrew Z. Adkins III, You Can’t Get Much Closer Than This: Combat With Company H, 317th Infantry Regiment, 80th Division, (Philadelphia: Casemate Publishers, 2005), 8.

16 “U.S., WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954” database, Fold3.com (www.fold3.com: accessed 13 October, 2022).

17 Adkins, You Can’t Get Much Closer Than This, 23.

18“80th Division Morning Reports,” web archives (https://www.80thdivision.com/WebArchives/MorningReports.html: accessed 13 October, 2022), sourced by Mr. Andrew Adkins, who was kind enough to help me fill up some of the holes in my research. A sincere thank you to him.; “Dale D. Nickols Collection: Veterans History Project,” Library of Congress, Loc.gov (https://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/bib/58793: accessed 1 November, 2022).

19 “Armored Blitz to Avranches,” Warfare History Network, accessed 5 March, 2024, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/armored-blitz-to-avranches/.

20 “The Falaise Pocket,” Normandie Tourisme, accessed 18 March, 2023, https://en.normandie-tourisme.fr/discover/history/d-day-and-the-battle-of-normandy/falaise-pocket/; “World War II: Closing the Falaise Pocket,” Historynet, accessed 15 November, 2023; “History of the 80th Division;” “Armored Blitz to Avranches,” Warfare History Network, accessed 15 November, 2023, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/armored-blitz-to-avranches/; “Northern France,” Army.mil, accessed 29 October, 2022, https://history.army.mil/brochures/norfran/norfran.htm.

21 80th Division After Action Reports,” web archives (https://www.80thdivision.com/WebArchives/AAReports.html: accessed 13 October, 2022); Adkins, You Can’t Get Much Closer Than This, 71-103.

22 Lembo, Lois and Reed, Leon. A Combat Engineer with Patton’s Army: The Fight Across Europe with the 80th “Blue Ridge” Division in World War II. (California: Savas Beatie, 2020), xxx.

23 Cole, Hugh M. United States Army in World War II European Theater of Operations: The Lorraine Campaign. (Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, 1997), 81.

24 Pearson, Ralph E. Enroute to the Redoubt. Chicago: Adam’s Printing Service, 1958. Another sincerest thank you to Mr. Andrew Adkins.

25 “80th Division Morning Reports,” web archives (https://www.80thdivision.com/WebArchives/MorningReports.html: accessed 13 October, 2022)

26 “The 80th Infantry Division during World War II,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed 2 November, 2022, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-80th-infantry-division; Elvin, Jan. The Box from Braunau: In Search of My Father’s War. New York: Amacom Books, 2009.

27 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed JUne 28, 2024, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-6th-armored-division.

28 “80th Division Plaque,” American War Memorials Overseas, Inc., accessed January 18, 2024, https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=561&MemID=1320.

29 “Key Wester Dies in Action in France,” The Miami Herald (Miami, Florida), October 5, 1944.

30 “History of the 80th Division;” “80th Division Morning Reports.”

31 “U.S., Headstone and Interment Records for U.S., Military Cemeteries on Foreign Soil, 1942-1949,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 19, 2023), entry for Daniel Fernandez, service number 34546292.

32 “U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1600s-Current,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com: accessed 28 October, 2022), entry for Jose Fernandez; “U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com: accessed 28 October, 2022), entry for Evangelina Fernandez, Key West, Monroe County, Florida.

33 “North Carolina, U.S., Death Indexes, 1908-2004,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com: accessed 28 October, 2022), entry for Delfin Fernandez; “Key Wester Dies in Action in France.”

34 “Daniel J. Fernandez,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed 2 November, 2022, https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/fernandez%3Ddaniel