PFC John Taylor Dale (December 18, 1923 – May 13, 1945)

4132nd Quartermaster Service Company, 577th Quartermaster’s Battalion

by Zayd Champion

Early Life

John Taylor Dale was born on December 18, 1923, in the town of Oakhill in Wilcox County, AL, the fourth child of Willie (1882) and Clemmie Dale (1894).1 John had four siblings: Elbert (1918), Willie (1920), Irma (1923), and Sam (1926).2 To support their family, the Dales farmed, likely sharecropping, in an unincorporated community named Allenton, not far from Oak Hill.3 Based on census data and slave manifests from Wilcox County, Dale’s parents likely descended from enslaved people who worked the land of a white family with the surname Dale.4 Maybe coincidently, a prominent white Calvary Veteran of the Confederacy also named John Taylor Dale lived in Allenton around the same time Willie and Clemmie Dale named their third son.5

Despite how difficult it must have been to raise their family in the Jim Crow South, the Dales wanted to ensure their children received an education. At least three of the five Dale children, including John, completed grammar school, an accomplishment for many children in the rural South, and even more so for black families, given the realities of segregated schools.6 This is quite a testament to how much his parents valued an education, despite not having received one themselves.7 While the Dale children received an education, they faced constant racial discrimination.

At some point in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, John’s father, Willie, died.8 Following Willie’s untimely passing, the Dale family moved to Pensacola.9 This move coincided with what is known as the Great Migration, when African Americans sought opportunities in larger, often northern city centers, and as a way out of the cycles of debt and humiliations they endured as sharecroppers. Many African Americans from areas like rural Alabama migrated to Pensacola during this time; a lesser-known part of the Great Migration in search of the growing export and shipping industry in Pensacola.10

Living in Pensacola would have been just as difficult a place for African Americans as anywhere else in the Jim Crow south. Much of Pensacola’s white population believed the city’s progress required keeping the black community in check through establishing, codifying, and enforcing segregation. The white population had particular disdain for the African Americans who migrated from Alabama and parts of rural Florida, as they saw them as ignorant and contemptuous of the prevailing social norms. These African Americans from Alabama and rural Florida faced discrimination from the local mixed-race creole community as well, who tried to distinguish themselves from the migrants as they saw their social status declining because the dominant white population did not care to differentiate between the communities of color.11

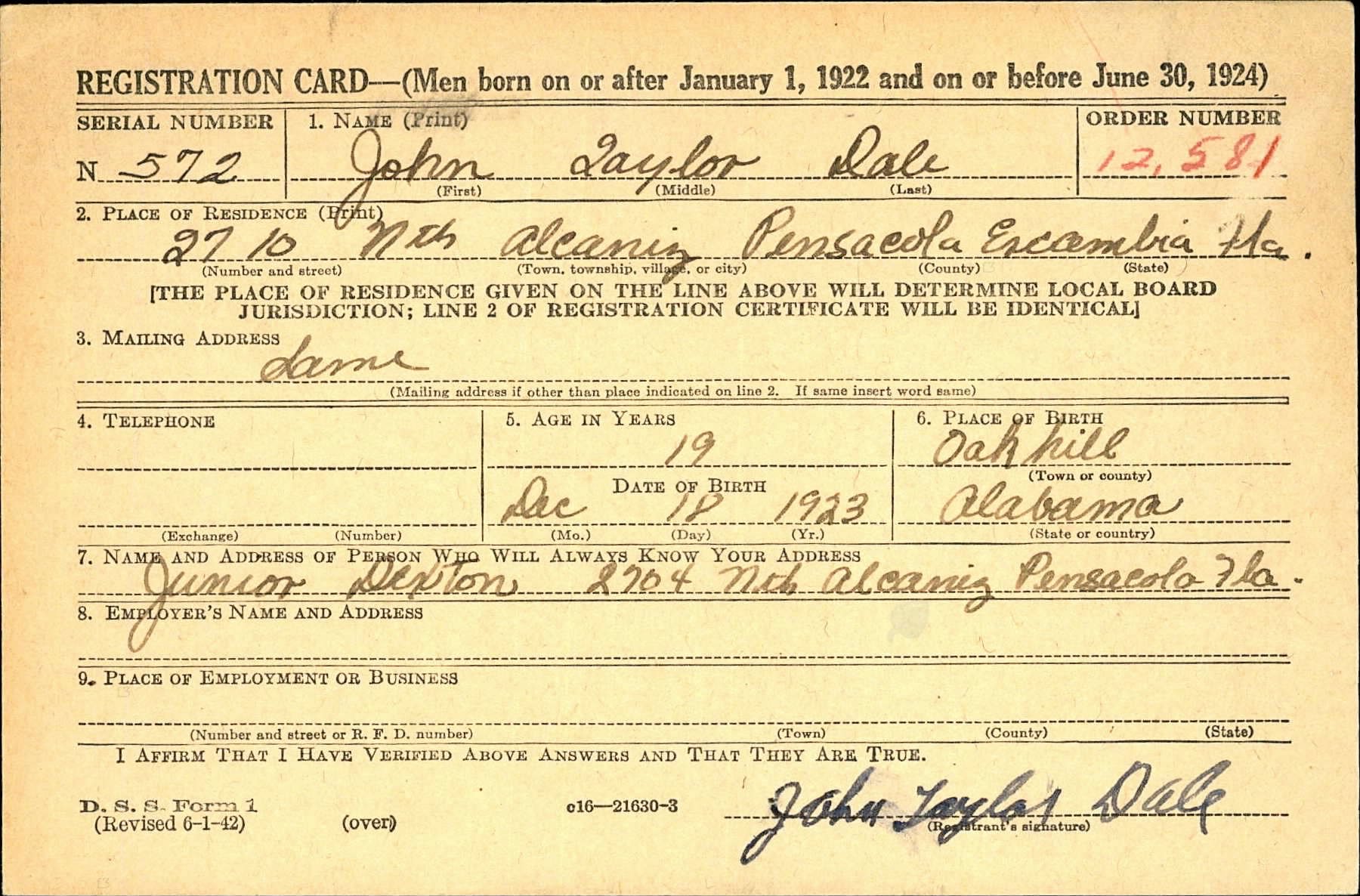

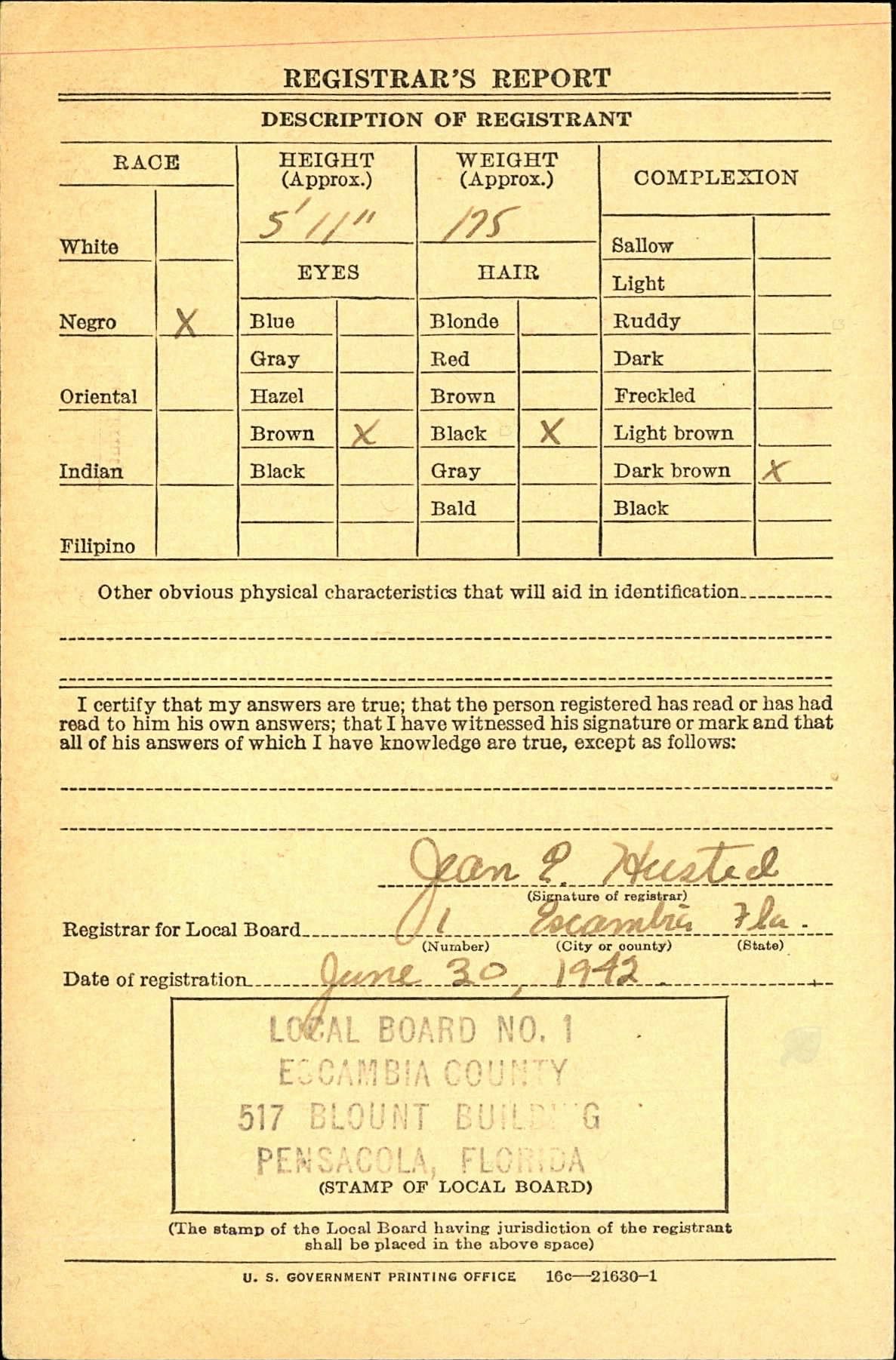

John and his mother remained together after the move to Florida, living with Solie Grace, Clemmie’s uncle.12 John’s older brother, Elbert, also moved to Pensacola, where he married his wife Eula.13 The family may have moved together, or one found employment and encouraged the others to join.14 In Pensacola, Clemmie worked as a private cook for a family, John as a “routesman,” a type of delivery driver, Elbert as a “semi-skilled chauffeur,” and Willie in warehousing.15 Both John and Elbert developed a sought-after skill, as not everyone could drive a motor vehicle in the 1940s.16 With the threat of war looming on the horizon, three of the Dale brothers registered for the draft. Elbert registered in 1940, John and Willie Lee registered 1942, as seen here.17

Military Service

In 1943, the US Army called each brother into service, John on February 2, Elbert on June 4, and Willie Lee on August 5. From Florida, John and his brothers enlisted at Camp Blanding, in Clay County, west of Jacksonville.18 Once inducted into the Army, their basic training likely took place at Camp Blanding.

African Americans faced substantial discrimination in the military. Jim Crow segregation in the US Army took many forms, from abusive treatment at the hands of white officers, to confinement in subpar housing conditions and terrible food. Some African American soldiers even pointed out that, in many ways, German prisoners of war (POWs) imprisoned on the same military bases received better treatment.19 German POWs in the Southern US could leave military bases and frequently found employment as contract laborers or in some cases the US Army hired them to work on base. Therefore, while the German POWs enjoyed ample freedom to find employment, among other pursuits, including eating in segregated restaurants, African American soldiers faced a Jim Crow segregation which sought to confine them on and off base.20

Following his training, the Army assigned John to the 4132nd Quartermaster Service Company, stationed in Kettering, England.21 Quartermaster companies serve as non-combat units assigned to provide support in a wide arrange of logistical roles; John and his comrades performed essential work, often near the front lines, and certainly within the range of artillery fire and other dangers.

The Quartermaster Corps transported men and supplies to the front, prepared food, did laundry, buried the dead, and performed other logistical tasks important to keeping the Army functional.22 High-ranking officers within the US military and white civilian leaders did not believe African Americans fit for combat roles or feared arming black men, so they assigned most African American men, like John, to the Quartermaster Corps or other service units in the military. Nevertheless, the Quartermaster Corps made it possible for the Allies to fight such a massive war by handling logistics and supplies. African American men made up large portions of these Corps, and their contribution to the war effort should not be overlooked.23

While in England, John and millions of other soldiers prepared for Operation Overlord, the codename for the amphibious landings in Normandy, France. The Quartermaster Corps played a vital role in landings that began on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and in the months that followed. Dale’s unit, the 4132nd Quartermaster Service Company, formed a part of the 577th Quartermasters Battalion, which, for the Normandy invasion, made up part of the 1st Engineers Special Brigade.24 On June 6, 1944, the 4132nd, along with the rest of the 1st Engineers Special Brigade, landed on Utah Beach and set up the Brigade’s headquarters following the initial push by infantry divisions.25 John and his comrades executed their mission in the midst of enemy artillery barrages. The 4132nd remained stationed in the Utah beach area until at least September 1944.26 Once the Allies pushed the Germans back, the Quartermaster Corps created the main supply lines for troops moving east across France. At times, the troops moved too rapidly for the establishment of supply lines. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, had to suspend or halt offensives and engagements while the Quartermaster Corps caught up with the front line.27

On May 8, 1945, the war in Europe officially came to an end. We do not know the circumstances of John’s death. We do not know when he went missing, just that the Army initially listed him as missing. Five days after the war’s end, the Army declared John Taylor Dale’s death on May 13, 1945. He was twenty-two.28 While he may have died during the war, since the Army declared his death after the war, and served in a non-combat unit, the official record lists John as having died non-battle.29 He may have died in the fighting near the end of the war. Or he may have been killed by an explosion or a fire, as the Army never recovered his body. The presence of unexploded ordinances made post-war reconstruction a fairly dangerous process; even in the twenty-first century, thousands of World War II-era bombs remain unexploded and occasionally cause problems in Germany.30 While we cannot know with certainty, John may have been killed in a racially motivated incident, as we do have evidence, however difficult to unearth, of African Americans dying at the hand of white soldiers as well.31

Legacy

Private First Class John Taylor Dale is memorialized through the inscription of his name on the Tablets of the Missing in the Lorraine American Cemetery in St. Avold, France.32

His name is one of thousands of soldiers whose final resting place may never be known. His unit is also memorialized at the beaches of Normandy in a monument dedicated to the 1st Special Engineers Brigade, shown here. The inscription upon the monument, which includes the 4132nd reads in French, “June 6, 1944, to our liberators, the town of Sainte Marie du Mont is grateful.”33

John was survived by his mother Clemmie Dale, his sister Irma Dale, as well as his brothers Elbert and Willie Lee Dale, who both made it home after their service in World War II. Following the war, Clemmie Dale moved to Detroit, MI, where she lived with her sister Ruth and her family.34 Clemmie lived there another thirty-six years before passing away on December 6, 1986, at the age of ninety-four.35 She rests in United Memorial Gardens in Superior, MI where she is remembered as a “loving mother.”36

John’s sister, Irma Dale, married Bernard Taylor and moved to Michigan sometime before 1950, where they lived with Hamilton Shaw and his family.37 Irma likely moved to Michigan to be near her mother, Clemmie, and other members of the family. By 1950, the family found themselves between Alabama, Michigan, and Florida. After the war, Elbert Dale returned to Pensacola and in 1952, he and his wife Eula divorced.38 At some point after his divorce, and before he married Sallie Mae Jenkins in 1978, Elbert moved to Jacksonville, FL.39 Elbert Dale passed away there in October 1989.40 John’s other brother, Willie Lee Dale, returned to Pensacola following the war, where he worked chemically treating lumber while living with the Gladdin family as a roomer.41 He lived the longest of the three brothers, dying in 2005 at the age of eighty seven. Willie Dale rests in Arlington National Cemetery.42

1. “U.S, World War II Draft Cards,” database, Fold3.com (https://www.fold3.com: accessed November 2, 2022) entry for John Taylor Dale, Pensacola, Escambia County; “Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Unaccounted for Remains,” database, Fold3.com (www.fold3.com: accessed April 1, 2023), entry for John T. Dale; “U.S., World War II Enlistment Records” database, Aad.archives.gov (https://aad.archives.gov: accessed November 2, 2022) entry for John T. Dale. The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency and John’s enlistment records list his birth year as 1922, although his draft card lists his birthdate in 1923.

2. “1930 U.S. Census,” database, Familysearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed November 2, 2022), entry for Willie, Clemmie, John, Elbert, Willie Jr., Irma, and Sam Dale, Allenton, Wilcox County, Alabama.

3. “1930 U.S. Census,” entry for Clemmie Dale.

4. “United States Census (Slave Schedule), 1850,” database, Familysearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org : accessed November 24, 2022), entry for Wm Dales.

5. “Confederate Pension and Service Records, 1862-1947,” database, Familysearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed November 27, 2022), entry for John Taylor Dale.

6. “U.S., World War II Enlistment Records,” entry for John T. Dale, Elbert Dale, William Lee Dale; Michael J. Solender, “Inside the Rosenwald Schools,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 30, 2021, (accessed April 1, 2023) https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-rosenwald-schools-shaped-legacy-generation-black-leaders-180977340/. It is likely that the Dale children attended a Rosenwald School, given that Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington primarily established these schools in rural Southern communities in the early-twentieth century.

7. “1930 U.S. Census.” Both Willie and Clemmie are listed as able to read and write but did not attend school.

8. “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Familysearch.org (www.familysearch.org: accessed November 2, 2022), entry for Clemmie Dale and John T. Dale, (John is listed as James T. Dale), Pensacola, Escambia County, Florida.

9. “U.S., World War II Enlistment Records,” entry for John T. Dale, Elbert Dale, William Lee Dale; “1950 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 1, 2023), entry for John, Elbert and William Dale. All of their enlistment records list Pensacola, FL, as the place of enlistment.

10. As African-Americans from Alabama settled Pensacola, the white population labeled the mixed-race Creole community as ‘colored’ in subsequent city directories. Donald H. Bragaw, “Status of Negroes in a Southern Port City in the Progressive Era: Pensacola, 1896-2000,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 51, no. 3 (1973): 281-302.

11. James R. McGovern, “Pensacola, Florida: A Military City in the New South,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 59, no. 1 (1980): 30-31.

12. “1940 U.S. Census,” entry for Clemmie Dale and John T. Dale.

13. “1940 U.S. Census,” entry for Elbert Dale.

14. “U.S. World War II Enlistment Records,” entry for Willie Lee Dale. We have found fewer records related to both Sam and Irma, who probably moved to Florida with the rest of the family, but they do not appear with their brother and mother in the 1940 census. Sam does not appear on any publicly available records after 1930, although Irma appears in the 1950 U.S. Census and in the Michigan marriage records, see below.

15. “U.S. World War II Enlistment Records,” entry for Elbert, John, and Willie Lee Dale; “1940 U.S. Census,” entry for Clemmie Dale.

16. “U.S. World War II Draft Cards,” entry for John, Elbert, and Willie Lee Dale.

17. “U.S. World War II Draft Cards,” entry for John Dale.

18. “U.S. World War II Draft Cards,” entry for John T. Dale, Elbert Dale, William Lee Dale; “1940 U.S. Census,” entry for John Roy Dexter, Pensacola, Escambia County, Florida.

19. Gary R. Mormino, “Gi Joe Meets Jim Crow: Racial Violence and Reform in World War II Florida,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 73, no. 1 (1994): 26-28.

20. Matthias Reiss, “Solidarity Among ‘Fellow Sufferers’: African Americans and German Prisoners of War in the United States During World War II,” The Journal of African American History 98, no. 4 (2013): 538.

21. “Installations and Operating Personnel Booklets, ETOUSA, Jan 1944-Oct 1945,” database, Fold3.com (www.fold3.com: accessed November 2, 2022) report as of June 1944, pg. 52; Jon Evans, “The Origins of Tallahassee’s Racial Disturbance Plan: Segregation, Racial Tensions and Violence During World War II,” Florida Historical Quarterly 79, no. 3 (2001): 346–364.

22. William F. Ross and Charles F. Romanus, The Quartermaster Corps: Operations in the War Against Germany (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, U.S. Army, 2004), Chapter One.

23. “What Can We Learn About World War II From Black Quartermasters?” The National WWII Museum, August 27, 2001, accessed February 9, 2023, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/world-war-ii-black-quartermasters.

24. “U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater, Historical Division: Records, 1941-1946,” database, Fold3.com (www.fold3.com: accessed November 2, 2022), 569f – Normandy Base Section Histories, Military Labor Service Quartermaster.

25. Alfred Beck, The Corps of Engineers: The War Against Germany (Washington DC: Center of Military History, 1985), Chapter XV.

26. “Installations and Operating Personnel Booklets, ETOUSA, Jan 1944-Oct 1945,” database, Fold3.com (www.fold3.com: accessed November 2, 2022) report of September, 1944.

27. Roland G. Ruppenthal, Command Decisions: Logistics and the Broad Front Strategy (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1990), 419.

28. “Unaccounted For Remains, Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency,” entry for John Dale.

29. “WWII Army Casualty List,” database, Fold3.com (www.fold3.com: accessed February 8, 2023), entry for John Dale. His death is listed as DNB (died non-battle).

30. Adam Higginbotham, “There Are Still Thousands of Tons of Unexploded Bombs in Germany, Left Over From World War II,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 2016, accessed February 9, 2023, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/seventy-years-world-war-two-thousands-tons-unexploded-bombs-germany-180957680/.

31. Here is just one recent article detailing the often untold story of racial violence African American soldiers faced in Europe. Justin Wm. Moyer, “Black WWII Soldiers asked a white woman for doughnuts. They were shot,” Washington Post, January 15, 2023 (https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/01/15/allen-leftridge-black-soldier-segregation/: accessed March 25, 2023).

32. “John T. Dale,” American Battle Monuments Commission, Tablets of the Missing, accessed February 9, 2023, https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/dale%3Djohn-1

33. “1st Engineer Special Brigade Monument,” American War Memorials Overseas, accessed February 8, 2023, https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=266&MemID=477, Monument Details. Thank you to the American War Memorials Overseas Incorporation for allowing the use of their image.

34. “1930 U.S. Census,” entry for Clemmie Dale, Detroit, Wayne, Michigan.

35. “Michigan, U.S., Death Index, 1971-1996” database, Familysearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed December 5, 2022), entry for Clemmie Dale, Detroit, Wayne, Michigan.

36. “U.S., Find a Grave Index, 1600s-Current,” database, Familysearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed December 5, 2022), entry for Clemmie Dale, Superior, Washtenaw County, Michigan.

37. “1950 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed February 8, 2023), entry for Erma B. Taylor, Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan. Irma’s name is misspelled in this entry, however it matches the marriage record with Bernard Taylor as well as the expected age of Irma in 1950; “Michigan, U.S. Marriage Records, 1867-1952,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 23, 2023), entry for Irma Blanche Dale and Bernard Taylor.

38. “Florida, U.S., Marriage Indexes, 1822-1875 and 1927-2001,” database, Familysearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed December 6, 2022), entry for Elbert Dale, 1952.

39. “Florida, U.S., Marriage Indexes,” entry for Elbert Dale, Aug 31, 1979.

40. “U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014,” database, Familysearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org: accessed December 6, 2022), entry for Elbert Dale, Oct 13, 1989. We have been unable to locate where he is buried.

41. “1950 U.S. Census,” entry for Willie Dale.

42. “Willie Lee Dale,” Army Cemeteries Explorer, accessed April 23, 2023, https://ancexplorer.army.mil/publicwmv/index.html#/search-all/results/1/CgREYWxlEgZXaWxsaWUaA0xlZQ–/.