Pvt. Lucious Bell (January 12, 1912 – June 19, 1945)

4466th Quartermaster Service Company

by Kevin Abreu

Early Life

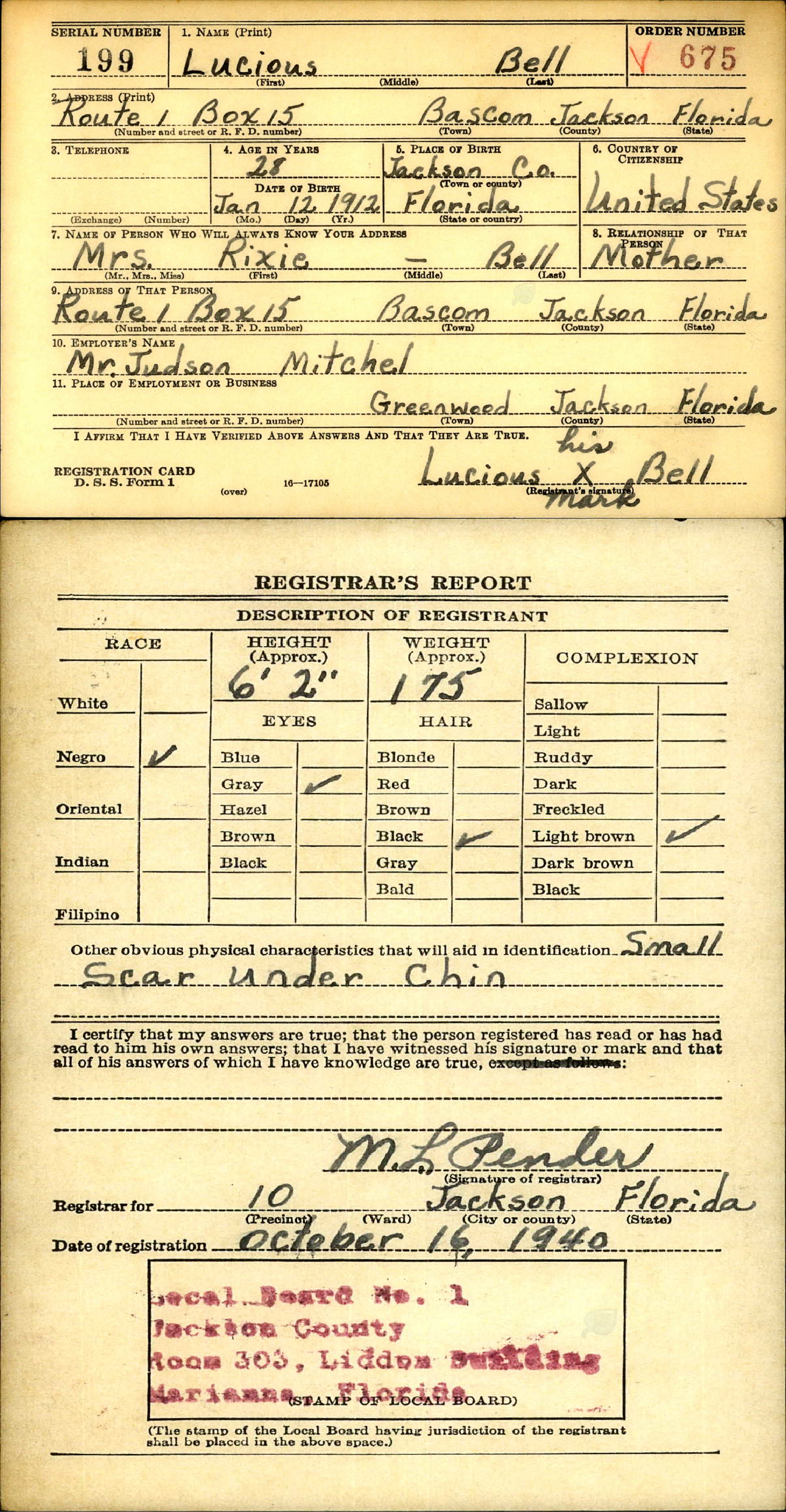

Lucious Bell was born in Bascom, Jackson County, FL, on January 12, 1912, to Mrs. Rixie Bell.1 They appear to have been a small family, mother and son, who relied on one another to survive in an unfriendly world. As African Americans living in the Jim Crow South, Lucious and his mother must have faced discrimination.2 Despite the difficulty these circumstances presented, Lucious completed grammar school.3 In the Jim Crow South, many African American communities did not have schools beyond grammar school and most students joined the workforce after completing the education available to them.4 Despite attending grammar school, Lucious could not read or write as indicated by his signing his draft registration card with his mark rather than a signature, as seen here.5

Bascom was a rural town, so Luscious most likely worked as a farm laborer until his enlistment. We do not know if he continued living with his mother or moved out at some point in the 1930s. In 1935, he married Geneva Smith in Jackson County.6 Their marriage must have been short-lived, as Lucious was listed as divorced on his enlistment record six years later.7 Lucious enlisted on February 18, 1941, giving his mother, Rixie, as his next of kin.8 Bell, an enlistee, volunteered immediately rather than wait to get drafted, maybe hoping for opportunities in the US Army. Bell joined an Army that was as segregated as the Jim Crow South that he left behind. The War Department had set up guidelines four years earlier, publicly stating that “The policy of the War Department is not to intermingle colored and white enlisted personnel in the same regimental organization.”9 Nevertheless, Bell wanted to serve his country in uniform even before the US entered World War II.

Military Service

Lucious Bell’s Army service began at Fort Benning, GA. Racial tensions were high when he arrived. Six days before Bell’s arrival, Felix Hall, an African American soldier, went missing from the base. Two months later, soldiers found his body hanging from a cliffside near the Chattahoochee River. Hall’s murder remains the first officially recognized case of lynching on a military base.10 The brutality Hall suffered may be among the most heinous examples of the horrible treatment African Americans faced in the segregated US military.

Following the War department’s policy, and under pressure from white civilian leaders, the Army not only segregated African American soldiers but primarily placed them in non-combat roles. African Americans primarily worked in service and logistical units, often in the Quartermaster Corps, as seen in this photograph of drivers in the 666th Quartermaster Truck Company, who served with the 82nd Airborne Division.11 This included driving trucks, delivering supplies, doing the laundry, and, once in battle, burying the dead. They also loaded, transported, and unloaded bombs, bullets, food, gasoline, and water to the front lines. They played an essential role in the war effort, as an army cannot fight without the supply chain pushing the charge forward.12 Bell, like most African Americans in the war effort, joined a service unit rather than a combat unit. He joined the 4466th Quartermaster Service Company, which performed logistical operations duties throughout the war.13

Many African American units, such as the 4466th Quartermasters, had all-Black soldiers commanded by white officers. In fact, at the start of the war, the regular Army had only five Black officers, three of whom were chaplains.14 As early as 1940, the Army began outlining plans to integrate Black officers from National Guard and Army Reserve units into active-duty roles. Though the Army introduced Black officers in a variety of units, most served in support units.15 Similarly, military leaders assigned Black troops to segregated pick-and-shovel brigades, non-combatants responsible for feeding the growing war machine. During the first three years of the war, approximately eighty percent of Black GIs did their duty in these service and support roles; even by the war’s end in 1945, the Army continued to relegate over ninety percent of Black GIs to service roles.16

While we do not know much about the circumstances, in October 1942, Bell suffered a compound fracture of his face.17 Maxillary fractures like Bell’s are most commonly caused by blunt force trauma to the face, often due to a motor vehicle accident, workplace injury, or physical assault.18 Any of these are possible for someone working as a Quartermaster. The Army sent Bell to the Second General Hospital.19 This hospital unit, organized out of personnel at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center, in New York City, trained before arriving in Oxford, England in July of 1942.20 For Bell to have been treated by this hospital unit, indicates that he arrived in England in 1942, making him part of an early wave of troops sent to England, potentially in support of the aerial bombing effort.21 Bell was discharged two months later, in December 1942.22

US support units, like Bell’s, spent nearly two years in England preparing for the Allied invasion which began on June 6, 1944. After the Allied landings at Normandy, Bell and the 4466th crossed the English Channel to help supply Allied lines that stretched across hundreds of miles of mainland Europe.

While we do not know exactly when Bell arrived in continental Europe, we know the 4466th served in the Rhineland, in support of the ground war campaigns in Germany in early 1945.23 The final push into German territory had come at a severe price as the Allies fought hard to repel the Nazi occupiers in France. Beginning on the beaches of Normandy, the Allied coalition crawled through France, liberating villages, towns, and cities along the way. American, British, Canadian, and French forces systematically drove the Germans back towards the Siegfried Line from the summer of 1944 through the early months of 1945– with the supply lines growing with every mile of territory taken from the enemy. The Siegfried Line, which the Allies fought to take during the Rhineland Campaign, became the last bastion of German defense.24

Starting in late summer 1944, the Allied front faced its most severe supply shortages. Despite their progress through France, the Allies had to stop because they ran out of everything, including gasoline.25 As Allied support units scrambled to resupply the front, Hitler initiated plans for what became the final German counterattack, the Ardennes Offensive. The Nazi plan aimed to strategically split the Allied forces concentrated on either side of the oft-called ‘impenetrable’ Ardennes Forest, inflicting significant casualties to alleviate the pressure along the Siegfried Line.26

The surprise attack began on December 16, 1944, in the cold, rugged, dense Ardennes Forest of Belgium and Luxembourg. Fighting lasted until late January 1945 with German troops spanning a seventy-five mile (120 kilometer) wide offensive front. Allied lines shifted to contain the attackers, creating a concave, or bulge, of defenders.27 At the culmination of the campaign, both sides had suffered significant losses, ultimately accounting for ten percent of American casualties throughout the war; over 75,000 soldiers in forty-one days of fighting.28 The confrontation became known in the US as “The Battle of The Bulge,” so called for the warped line of Allied defenders through which Germans attempted to pierce a hole at the Ardennes. Nevertheless, Allied counter attacks once again repelled the German forces, effectively shrinking the bulge. After failing to accomplish its objectives in early 1945, German forces never again pushed into Allied-controlled territory.29

The Allies’ Rhineland Offensive began in full force in early February, 1945. Primarily, the Allies sought to penetrate the German Siegfried Line, a construction of hundreds of bunkers and machine gun emplacements meant to defend the German border from an Allied invasion.30 Over the next six weeks, soldiers and equipment needed to move across the front, a distance of over 300 miles (480 kilometers) from where ships landed in Normandy. Quartermaster companies again played a vital role in the effectiveness of the Allied push into the Rhineland. Bell and his comrades transported men and supplies across the snow-covered regions of Northern France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, eventually crossing into Germany, while under long range artillery fire and aerial bombing.31

Lucious Bell died on June 19, 1945, four years after his enlistment and over a month after the war in Europe officially ended.32 Despite the end of fighting, challenging conditions persisted for years for millions of people. American troops, and in particular Black units, worked to help rebuild communities that had been devastated by six years of war. Bell died while participating in the efforts to secure and rebuild Europe after the war. He likely lost his life while working to rebuild war-torn areas of France or Germany, or while reburying the dead in their final resting places. 33

Legacy

Lucious Bell was survived by his mother, Rixie Bell.34 After his death, Lucious was buried at the Rhone American Cemetery alongside 850 brave men who also paid the ultimate price. African American soldiers struggled with institutionalized racism at home in a nation that saw them as second-class citizens, yet they proudly answered the call to serve their country in a war against tyranny abroad. This juxtaposition served as a catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement. In a 1942 letter to the editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, a prominent Black newspaper, James Thompson asked if he should sacrifice to live life “half American,” ultimately concluding that while victory abroad should be at the forefront, Black Americans should not lose sight of their fight for “true democracy at home.”35 This letter, which highlighted the incongruity of fighting for liberty abroad while not having it at home, gave rise to the Double-V Campaign. The first “V” was for victory against external enemies and the second was for victory against domestic oppressors. Many African American GIs threatened a “March on Washington” to protest segregation in the military. In 1948, President Truman signed Executive Order 9981, which removed segregation from the US Armed forces.36

Bell was just one of many brave soldiers whose stories have long been overlooked because of the color of their skin. His story exemplifies the sacrifices and perseverance of Black soldiers who bled for their country and the liberation of others. Many of the men of color who faced racial injustices at home and in military service became leaders of the Civil Rights movement. They brought the ideals they fought for overseas back to the US, forcing a nation based on principles of liberty and equality to face its shortcomings. Unfortunately, Private Lucious Bell, who died on June 19, 1945, never got to reap the rewards of his sacrifices. His headstone, at the Rhone American Cemetery, Plot B, Row 3, Grave 24, reminds us that he was one of those African Americans who died for our liberty.37

1 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2238/records/12686930?tid=&pid=&queryId=35562350-9492-429b-a255-b232cf3d043f&_phsrc=qFr241&_phstart=successSource: accessed February 5, 2025), entry for Lucious Bell.

2 Mormino, Gary R. “GI Joe Meets Jim Crow: Racial Violence and Reform in World War II Florida.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 73, no. 1 (1994): 23–42.

3 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8939/records/3205293?tid=&pid=&queryId=f3c71775-2119-422e-9c0a-e8528d3a2f44&_phsrc=qFr250&_phstart=successSource: accessed October 28, 2024), entry for Lucious Bell, service number 34007009.

4 John H. Best, “Education in Forming the American South,” History of Education Quarterly 36, no. 1 (1996): 49-50.

5 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” Ancestry.com, entry for Lucious Bell.

6 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1923-1982,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61369/records/1058719?tid=&pid=&queryId=710c308b-7fd6-4849-8178-b4f7f6a1c8c1&_phsrc=qFr245&_phstart=successSource: accessed Nov 4, 2022), entry for Lucious Bell and Geneva Smith.

7 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” Ancestry.com, entry for Lucious Bell.

8 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” Ancestry.com, entry for Lucious Bell.

9 Patrick J. Charles, “The Long Fight to Achieving Military Integration,” Air Force Historical Research Agency, accessed February 12, 2025, https://www.dafhistory.af.mil/Our-Research/Military-Integration/; United States Government Printing Office, Washington, “Freedom to Serve: Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services,” Truman Library, 1950, accessed February 12, 2025, https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/freedom-to-serve. These sources offer separate uses of the quoted text, though it is not clear which of the two contains the original provenance. The first source attributes the quote to a letter written by Lieutenant General Henry Arnold on October 8, 1940. The second source suggests that the text was first issued (in an official sense) the following day in a statement given by the White House.

10 Fortin, Jacey, and Alexa Mills. 2021. “Felix Hall, a Soldier Lynched at Fort Benning, Is Remembered after 80 Years.” The New York Times, August 20, 2021, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/20/us/felix-hall-soldier-lynching-wwii.html.

11 National Archive Catalogue, Record Group 208, Records of the Office of War Information Series: Photographs of the Allies and Axis, created May 1945, Accessed April 2025, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535533.

12 “What Can We Learn about World War II from Black Quartermasters?,” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, (https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/world-war-ii-black-quartermasters: accessed April 7, 2022)

13 Unit Citation and Campaign Participation Credit Register, (Washington: Department of the Army, 1961), 496.

14 Ulysses Lee, United States Army in World War II, Special Studies, “The Employment of Negro Troops,” (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1966), 29.

15 Lee, United States Army in World War II, 191-200.

16 “What Can We Learn,” The National WWII Museum.

17 “U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/61817/records/2141269?tid=&pid=&queryId=a736c053-43d1-4e70-b9c2-5d6ebfbf9ba5&_phsrc=qFr202&_phstart=successSource: accessed October 28, 2024) entry for Lucious Bell, service number 34007009.

18 Jane Meldrum, Yasamin Yousefi, and Andrew C. Jenzer “Maxillary Fracture,” National Institutes of Health: National Library of Medicine, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562162/: accessed February 5, 2025); “Compound Fracture: What Is It, Types, Symptoms & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic. Accessed Nov 4, 2022, (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21843-compound-fracture: accessed February 5, 2025).

19 “U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files,” database, Ancestry.com entry for Lucious Bell.

20 “Second General Hospital Collection | Archives & Special Collections.” n.d. www.library-Archives.cumc.columbia.edu. Accessed December 7, 2022, https://www.library-archives.cumc.columbia.edu/finding-aid/second-general-hospital-collection-1942-1952.

21 “The Friendly Invasion” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, Accessed October 28, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/friendly-invasion.

22 “U.S. WWII Hospital Admission Card Files,” database, Ancestry.com entry for Lucious Bell.

23 Unit Citation and Campaign Participation Credit Register, (Washington: Department of the Army, 1961), 496.

24 Ted Ballard, Rhineland, 15 September 1944 – 21 March 1945, (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2019), 7.

25 Ballard, Rhineland, 12-13.

26 “Battle of the Bulge,” The National WWII Museum, (https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/topics/battle-bulge: accessed February 5, 2025).

27 “Battle of the Bulge, December 1944 – January 1945,” United States Army, (https://www.army.mil/botb/: accessed February 5, 2025).

28 “Battle of the Bulge,” The National WWII Museum, (https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/battle-of-the-bulge: accessed February 5, 2025); “Battle of the Bulge,” Center of Military History, United States Army, (https://www.history.army.mil/html/reference/bulge/index.html: accessed February 5, 2025).

29 Ballard, Rhineland, 31.

30 Ballard, Rhineland, 7.

31 William F. Ross and Charles F. Romanus, The United States Army in World War II, The Technical Services, “The Quartermaster Corps: Operations In The War Against Germany,” (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1991), 425-438.

32 “Headstone Inscription and Interment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/9170/records/86673?tid=&pid=&queryId=0f4e6165-26d4-42f6-ad50-224ccf5c1a67&_phsrc=qFr209&_phstart=successSource: accessed October 28, 2024), entry for Lucious Bell, service number 34007009.

33 Ross and Romanus, The United States Army, “The Quartermaster Corps,” 438-440.

34 “Headstone Inscription and Interment Records,” database, Ancestry.com, entry for Lucious Bell.

35 James G. Thompson, “Should I Sacrifice to Live ‘Half-American?’,” The Pittsburgh Courier, January 31, 1942.

36 “Birth of the Civil Rights Movement, 1941-1954 – Civil Rights,” U.S. National Park Service, (https://www.nps.gov/subjects/civilrights/birth-of-civil-rights.htm: accessed Nov 4, 2022).

37 “Lucious Bell,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed October 28, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/bell%3Dlucious.