Pvt. Clifford C. Adams (November 13, 1923 – November 8, 1944)

761st Tank Battalion

by Amelia Montout

Early Life

Clifford Columbus Adams was born on November 13, 1923, to Helen and Charles (or Chas) Adams.1 His mother Helen (1904) grew up in Miami, FL, where her parents George and Mattie Evens owned a house – a rare feat for African Americans in the early twentieth century.2 Helen married Charles Adams sometime in the early 1920s and they moved frequently, likely for employment opportunities. They had their first son, Charlie Jr., in 1922 at Coleman, FL, and Clifford a year later at Charleston, SC.3 At some point before 1935, Charles Sr. died, and Helen had a third son, Jimmie Lee Singleton, named after his father.4 By 1935, Helen returned to Miami to raise her three sons alone, renting a house near her parents just outside Overtown.5

Founded at the end of the nineteenth century, Overtown became the historic center of Miami’s black community.6 During Helen’s lifetime, it served as the center of commerce for African Americans and, like other segregated parts of Miami, lacked municipal facilities, suffered from housing shortages, and had unsafe housing construction. Diseases like tuberculosis, syphilis, and influenza disproportionately impacted Miami’s black neighborhoods, but instead of helping the black communities, Miami’s white leaders wanted to hide Overtown and its residents from tourists and push them into smaller enclaves in the name of white security. In the mid-1930s, the city of Miami embarked on its “Twenty-Year Plan for Dade County” which extended Jim Crow, codified segregation through racially homogenous neighborhoods, and expanded the white Central Business District.7 Despite these challenges, black entrepreneurs transformed Overtown into a center of arts and culture: at its heyday between the 1940s and the 1960s, it was known as a “Harlem of the South” and hosted famous black intellectuals, literary artists, and entertainers, including Thurgood Marshall, W.E.B. DuBois, Zora Neale Hurston, Ella Fitzgerald, Josephine Baker, and Sammy Davis Jr., to name only a few.8

Despite the difficulties that her family must have faced in segregated Miami, Helen prioritized her children’s education and put all three boys through grammar school and at least part of high school. To support her family, she worked fifty-two hours a week as a laundress.9 By the early 1940s, Charlie Jr. found work at the Dade County Hospital, and Clifford may have also worked with him.10 Clifford’s draft registration card noted he was unemployed in 1942, but enlistment records a year later indicated that he worked as hospital attendant.11 It is possible he worked off the books, in a position that the Dade Hospital did not recognize.

Military Service

Adams registered for the draft in 1942, at the age of eighteen, and the Army called him to service a year later. He arrived at Camp Blanding, FL, for training on January 19, 1943.12 In 1940, Congress officially prohibited racial discrimination in the armed forces, but entrenched discrimination nevertheless shaped black soldiers’ experiences during World War II. The US military leaders avoided putting African Americans in direct combat roles because of fear about the “danger” of arming black soldiers and prejudices concerning their ability to fight. Throughout the war, most African American soldiers served in quartermaster or supply units, where they were responsible for cooking, cleaning, and maintaining America’s military forces.13 Adams, however, joined one of the few segregated combat units in the US Army. He became a private in the 761st Tank Battalion, also known as the “Black Panthers.”14

Between April 1942 and June 1944, the Black Panthers trained first at Camp Claiborne, LA, then at Fort Hood, TX. At both camps, they faced discrimination and the dangers of the Jim Crow south. At Camp Claiborne, the commanders quartered all African American soldiers at the back of the camp, near the sewage. If they had to take a bus off base, only ten African Americans could travel at a time, the remaining African American soldiers had to walk. At Fort Hood, they lived in threat of violence from the other white soldiers, officers, and inhabitants of the nearby towns if they left the camp.15 There, the 761st lost an officer due to discrimination inside and outside of the camp. Jackie Robinson, who was already famous for being the first African American to play in baseball’s major leagues, joined 761st as a lieutenant but was arrested outside of Fort Hood for refusing to sit at the back of a local bus. The Fort Hood commanders court-martialed Robinson for reportedly causing a scene and disrespecting a superior officer; the Army later acquitted him, largely due to the efforts of the NAACP, but by that time it was too late for Robinson to rejoin the 761st.16 In the midst of these trying conditions, however, Adams met and married Lutishia Mulder, who lived near Fort Hood.17

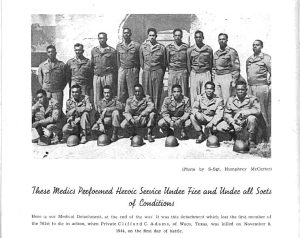

The 761st had thirty-six officers, six of whom were white, and 676 black soldiers, who made up six companies. There were four combat companies – A (Able), B (Baker), C (Charlie), and D (Dog) – three of them served in M4A3 Medium Sherman Tanks, and one in M5 Stuart Light Tanks. There was also a service and support company which kept the battalions supplied, and a headquarters company.18 The unit also had a medical detachment, seen here, to which Adams belonged.19 The Army likely assigned him to the Medical Detachment because of his experience as a hospital orderly.

On June 9, 1944, the 761st received orders to start the necessary preparations to sail across to Europe. Exactly two months later, the battalion traveled by train from Fort Hood, TX to Camp Shanks, NY, from which they shipped out to England. The African American soldiers on the train could only move around during the night due to white fears that their presence might cause “racial problems” among the passengers, and when sailing to Europe, they had to stay below deck because the military leaders believed they might be “troublemakers and not obey orders.”20 After over a month of travel, the 761st was the first African American tank battalion to arrive at the European Theater. When they arrived, the Third Army commander General Patton addressed the 761st, saying, in part:

Everyone has their eyes on you and is expecting great things from you. Most of all, your race is looking forward to you. Don’t let them down, and damn you, don’t let me down.21

On September 8, 1944, the 761st landed at Avonmouth, England, and stayed a few weeks at Wimborne and Dorset, England, to prepare for battle. In October, the Army command assigned the 761st to the Third US Army, and sent them across the channel, where they landed at Omaha Beach on October 9, 1944.22 The Allies first landed at Omaha Beach on D-day, June 6, 1944, after which they slowly pushed into northern France, ousting the German forces town by town. Two months later, the Allies launched an attack on a second front, landing at France’s southern coast and moving inland. By the time the 761st arrived, the Allied forces had strong footholds in northern and southern France but continued to meet German resistance as they moved east toward the Franco-German border.23

Once they landed at Omaha Beach, the 761st travelled over 400 miles to join the Third Army’s 26th Division on the front lines in northeastern France. They received their first combat mission on November 8, 1944, when their commander instructed them to take a strategic hill near the small town of Vic-sur-Seille, about thirty miles southeast of the city of Metz, near the German border. That day, two platoons from Company A crossed the Vic-sur-Seille river and reached a heavily mined area when they came under fire from enemy forces. During this engagement, Pvt. Adams was helping a wounded soldier when an exploding shell struck him in the chest; he died of his wounds later that day. He was twenty-one years old.24

Legacy

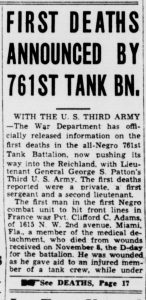

Pvt. Clifford C. Adams was not only the first casualty of the 761st Tank Battalion, but the first ever member of a segregated US tank unit to die in combat. Both the white-run media and the African American press, such as The Michigan Chronicle seen here, reported his death as that of “the first man in the first Negro combat unit to hit front lines in France.”25 The US Army awarded Adams a Purple Heart for his sacrifice in battle. After the war, he was reburied alongside over ten thousand other Americans at the largest American World War II cemetery in Europe, in St. Avold, France.26 His final resting place is at the Lorraine American Cemetery in Plot A, Row 16, Grave 15, about thirty miles from where he died.27 Both of the Adams’ brothers, Charlie and Jimmie, also served in the armed forces during the war, but returned home safely. They passed away in 1992 and 1986, respectively.28 Adams’ wife Lutishia never remarried and passed away on January 2, 2010. She is buried in a National Cemetery in Sacramento Valley, CA. Her headstone reads, “Wife of Pvt. Clifford Adams USA.”29

Following Adams’ death, the 761st fought for 183 days across Europe, losing a total of thirty-four men. They fought in the Battle of the Bulge in the terrible winter of 1944 and participated in the liberation of several concentration camps in Austria. After the war ended, the 761st remained in occupied Germany, and did not return to the US until November 1947. One of the most valuable tank units in the war, the 761st was officially disbanded on March 5, 1955.30

Pvt. Adams will always be remembered for his compassion and bravery on the battlefield. As an African American serviceman in World War II, he was part of a generation that helped inspire the Civil Rights Movement. He sacrificed his life trying to save another’s, in a world that did not fully recognize his heroism or equality. Not until 1978 did the US government recognize the bravery and accomplishments of the Black Panthers, when President Jimmy Carter issued the 761st an overdue Presidential Unit Citation For Extraordinary Heroism, in which he declared:

The courageous and professional actions of the members of the “Black Panther” battalion, coupled with their indomitable fighting spirit and devotion to duty, reflect great credit on the 761st Tank Battalion, the United States Army, and this Nation.31

1 “U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Clifford Columbus Adams, serial number 312; “U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007) database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Clifford Columbus Adams, SSN 263264734. The Social Security claims application lists Adam’s DOB as 1921, but this seems to be an error, as all the rest of the records indicate that he was born in 1923.

2 “1920 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for George Evans, Precinct 17, Dade, County, Florida.

3 “U.S., WWII Draft Registration Card,” entry for Clifford Columbus Adams, serial number 312, and entry for Charlie Christopher Adams, serial number 85.

4 “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed April 20, 2021), entry for Jimmie Lee Singleton, SSN 267304103. The 1940 census lists Jimmie as a stepson, while the 1935 census lists him as a son. Helen is listed as his mother in the Social Security records, so it is likely that she was Jimmie’s biological mother.

5 “1935 State Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Helen Adams, Dade County, Florida.

6 For more on Overtown’s history, read about the neighborhood on Black Archives, accessed September 21, 2021, https://www.bahlt.org/overtown.

7 Porsha Dossie, “The Tragic City: Black Rebellion and the Struggle for Freedom in Miami, 1945-1990” (MA diss., University of Central Florida, 2018), 22 – 29.

8 Dorothy Jenkins Fields, “A Look Back at Miami’s African American and Caribbean Heritage,” Miami and Beaches, accessed September 7, 2021, https://www.miamiandbeaches.com/things-to-do/history-and-heritage/miamis-african-american-caribbean. For more on Overtown and segregation in Miami, see this presentation on “Race, Housing, and Displacement in Miami,” https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/0d17f3d6e31e419c8fdfbbd557f0edae.

9 “1940 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Helen Adams and family, South Miami, Dade County, Florida.

10 “U.S, World War II Draft Registration Card,” entry for Charlie Christopher Adams.

11 “U.S, World War II Draft Registration Card,” entry for Clifford C. Adams; “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Clifford C. Adams, service number 34540536.

12 Ibid.

13 Jon Evans, “The Origins of Tallahassee’s Racial Disturbance Plan: Segregation, Racial Tensions and Violence During World War II,” Florida Historical Quarterly 79, no. 3 (Winter 2001): 346 – 364.

14 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Clifford C. Adams, service number 34540536.

15 Craig A. Trice, “The Men That Served with Distinction: ‘The 761st Tank Battalion,’” (M.A. diss, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1997), 6, 17.

16 John Vernon, “Jim Crow, Meet Lieutenant Robinson,” Prologue Magazine 40, no. 1 (Spring 2008): accessed October 7, 2021, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2008/spring/robinson.html.

17 “Headstone Inscription and Internment Records;” “1940 US Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Lutishia Mulder, Precent 2, McLennon County, Texas.

18 Trice, “The Men That Served with Distinction,” 20, 23-24.

19 Trezzvant W. Anderson, Come Out Fighting: the Epic Tale of the 761st Tank Battalion 1942-1945 (Germany: Salzburger Druckerei Und Verlag, 1945), 118.

20 Trice, “The Men That Served with Distinction,” 27-28.

21 Ibid, 29.

22 Ibid, 28 – 29.

23 For details on the combat operations in France between June and October 1944, see Martin Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 1993), https://history.army.mil/html/books/007/7-5-1/CMH_Pub_7-5-1_fixed.pdf.

24 Trice, “The Men That Served With Distinction,” 28 – 32; Ed Lengel, “The Black Panthers Enter Combat: The 761st Tank Battalion, November 1944,” The National WWII Museum, accessed October 11, 2021, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/black-panthers-761st-tank-battalion; “U.S., WWII Hospital Admission Card Files,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Clifford C. Adams, service number 34540536.

25 “First Deaths Announced By 761st Tank BN.,” The Michigan Chronicle (Detroit, Michigan), December 16, 1944, p. 13, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045324/1944-12-16/ed-1/seq-13/. Adam’s death also noted in The Apache Sentinel, The New York Age, and The Pittsburgh Courier.

26 “Lorraine American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed October 8, 2021, https://www.abmc.gov/Lorraine.

27 “Clifford C. Adams,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed March 29, 2021, https://www.abmc.gov/decedent-search/adams%3Dclifford-0.

28 “U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2021), entry for Charlie C. Adams, SSN 261202012, and Jiummie L. Singleton, SSN 267304103.

29 “Lutishia Adams,” National Cemetery Administration, accessed March 29, 2021, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/ngl/ngl#results-content; “Lutishia Adams (1921-2010),” Find a Grave, accessed March 29, 2021, www.findagrave.com/memorial/49016155/lutishia-adams.

30 Trice, “The Men That Served with Distinction,” 39 – 47. For the 761st’s actions during the Battle of the Bulge, see Ed Lengel, “Black Panthers in the Snow: The 761st Tank Battalion at the Battle of the Bulge,” The National WWII Museum, accessed October 11, 2021, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/black-panthers-761st-tank-battalion-battle-of-the-bulge.

31 Jimmy Carter, “The Presidential Unit Citation (Army) For Extraordinary Heroism To The 761st Tank Battalion, United States Army,” 761st.com, accessed March 29, 2021, http://www.761st.com/18update/2018a/index.php/history/presidential-unit-citation.