Glenmore Bachman // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

At the Glassford and Henderson Colchester store (1760-1761) in Fairfax County, Virginia, evidence of slaves in the records was mostly through indirect mentions (“by your negro wench”) or by the purchase of items used mostly by those enslaved (osnaburg, a fabric used to make clothing). Negro Jack was an exception; he was a slave belonging to Mr. Linton’s estate and yet, had his own account in the store. Jack visited the store once in 1760 (November 9) and four times in 1761 (February 3, August 22, September 16, and December 4). Jack purchased mostly rum.[1] These purchases appear to be in line with the thinking of the time, as “colonial Americans, at least many of them, believed alcohol could cure the sick, strengthen the weak, enliven the aged, and generally make the world a better place.”[2] Was Jack suffering from an illness that drew him to rum? In addition to alcohol, another of Jack’s purchases was a bottle of Turlington’s Balsam of Life, a patent medicine created by Robert Turlington in 1744.[3] It was said to treat “kidney and bladder stones, cholic, and inward weakness,” in addition to many other ailments.[4] Beyond liquids, Jack also purchased building materials: nails and HL hinges that were used for doors or cabinets, depending on their size.[5]

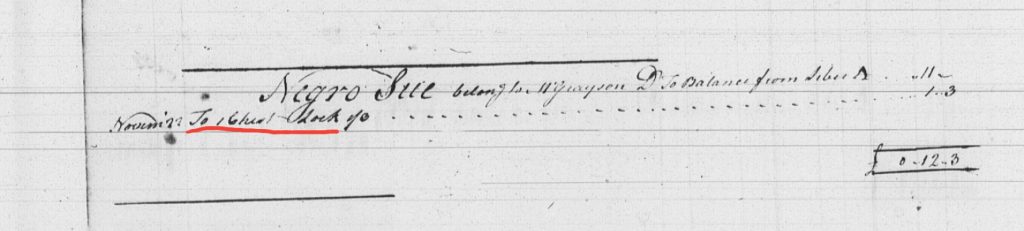

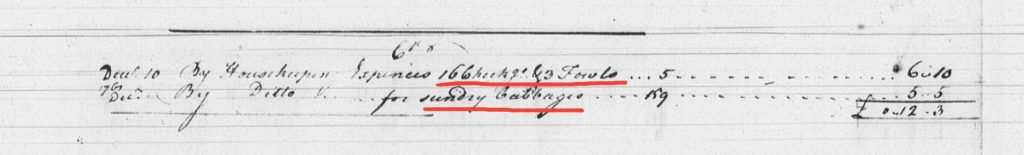

The only other slave with her own account was Negro Sue who belonged to Mr. Benjamin Grayson. Sue visited the store three times: once to purchase a chest lock (November 22, 1760) and twice to pay her bill through selling to the store chickens, ducks, and cabbages (December 10, 1760 and December 1761).[6] Purchasing a chest lock indicates she owned something she chose to keep to herself, as well as a chest to keep those things. Being able to sell chickens, ducks, and cabbages to the store indicates she had the ability and space to tend a garden and maintain her own animals, separate from Mr. Grayson. Sue may not have been free, but she had the freedom to create something that enabled her to have a little spending money of her own.

Both of these individuals’ accounts paint a more detailed picture of slavery in colonial America. Slaves with the relative autonomy to make and spend their own money show that the social atmosphere, at least in 1760-61 Virginia, might have been much more relaxed towards the enslaved. Not only did store manager, Alexander Henderson, cultivate relationships with Fairfax County’s white residents, but its enslaved population as well. What Negro Jack and Sue mean for understanding the complex social ties of the time is that relations with slaves from the colonial period up to the Civil War were likely more complicated and more diverse than might be believed.

[1] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 114 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[2] Ed Crews, “Rattle-Skull, Stonewall, Bogus, Blackstrap, Bombo, Mimbo, Whistle Belly, Syllabub, Sling, Toddy, and Flip: Drinking in Colonial America,” Trend & Tradition: The Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg (Holiday 2007), accessed March 15, 2017, http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/holiday07/drink.cfm.

[3] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761 folio 114 Debit;

Kate Kelly, Old World and New: Early Medical Care, 1700-1840, The History of Medicine (New York: Infobase Publishing, 2010), 98.

[4] George B. Griffenhagen and James Harvey Young, Old English Patent Medicines in America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2009), accessed March 29, 2018, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/30162/30162-h/30162-h.htm.

[5] “H & HL Hinge Hardware,” Historic Housefitters Co., accessed March 16, 2017,

https://www.historichousefitters.com/Hand%20Forged%20Iron/H%20HL%20HINGE%20HARDWARE.

[6] Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, folio 79 Debit/Credit.