Christopher José // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

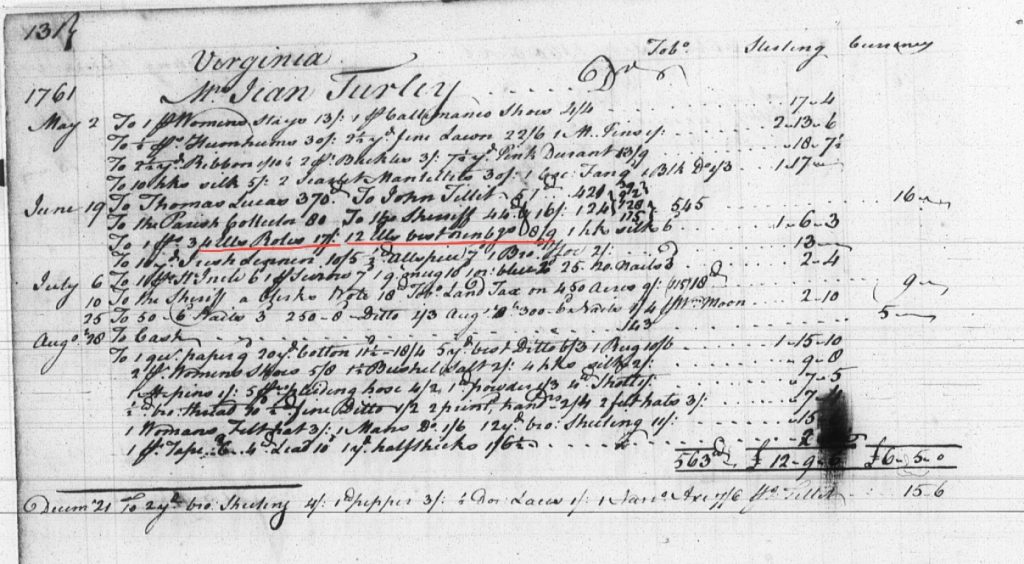

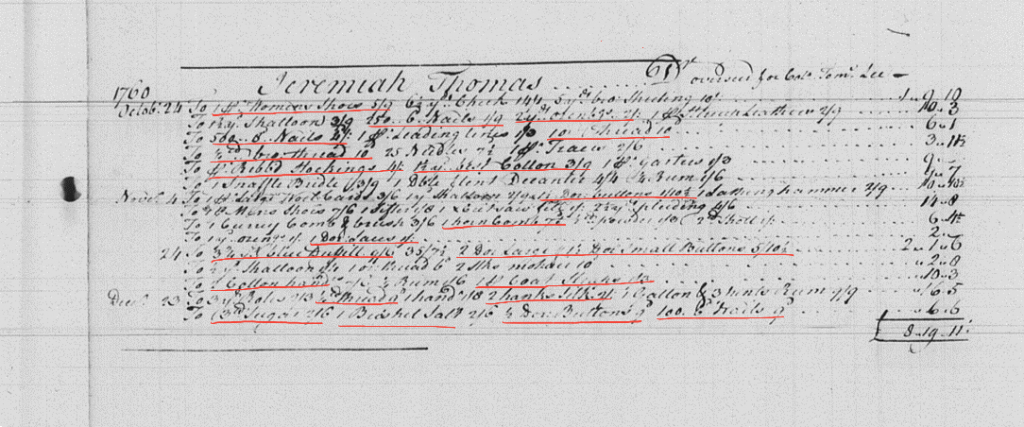

To find answers from the past, historians search endlessly through documents of all types, even store ledgers. These answers result in the researcher being able to glimpse into the past and learn from it. In the end, we better understand the culture and methods of those who came before us. This blog will explore one client of the Glassford & Henderson Colchester Store in 1760-1761, Joseph Jackson’s purchases and his method for buying, along with the mystery that surrounded this man’s profession.

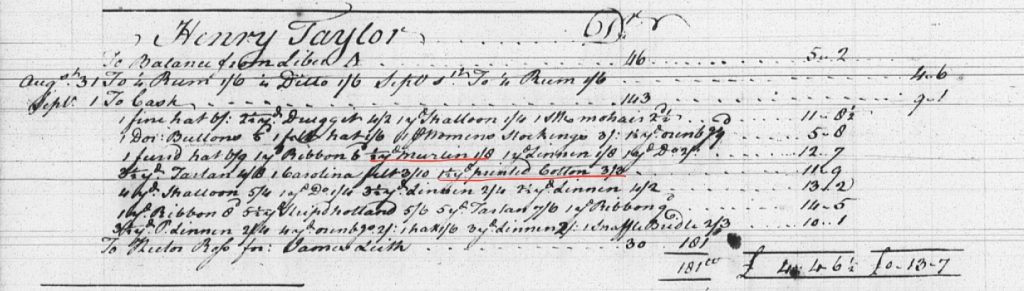

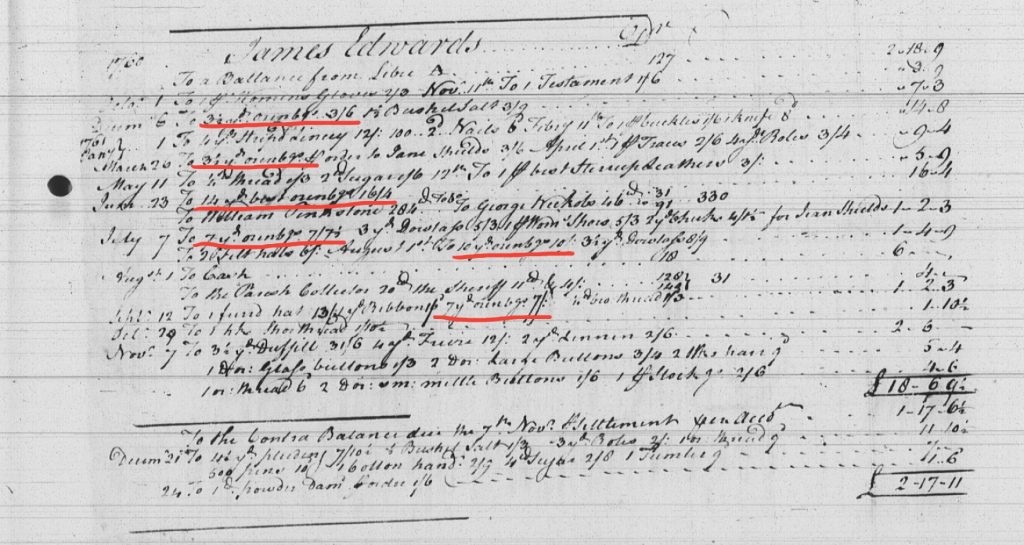

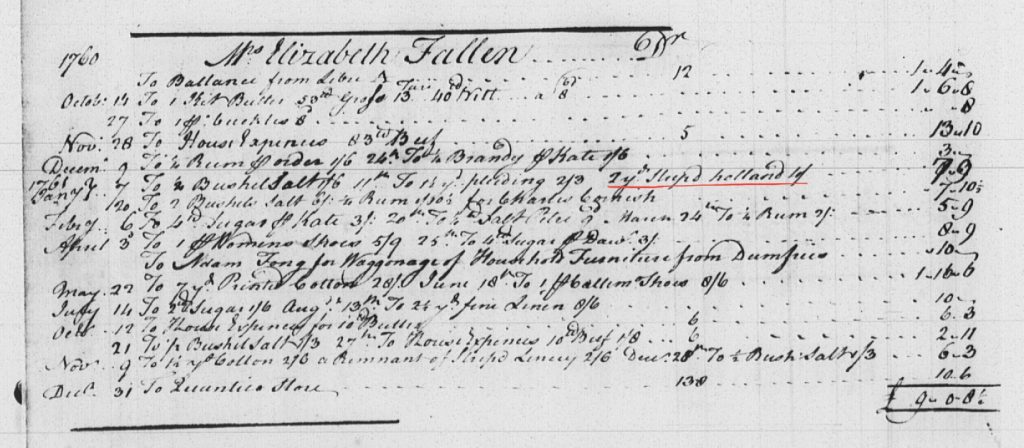

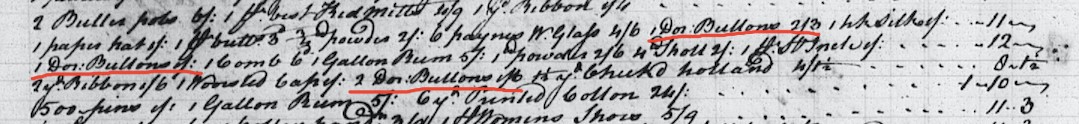

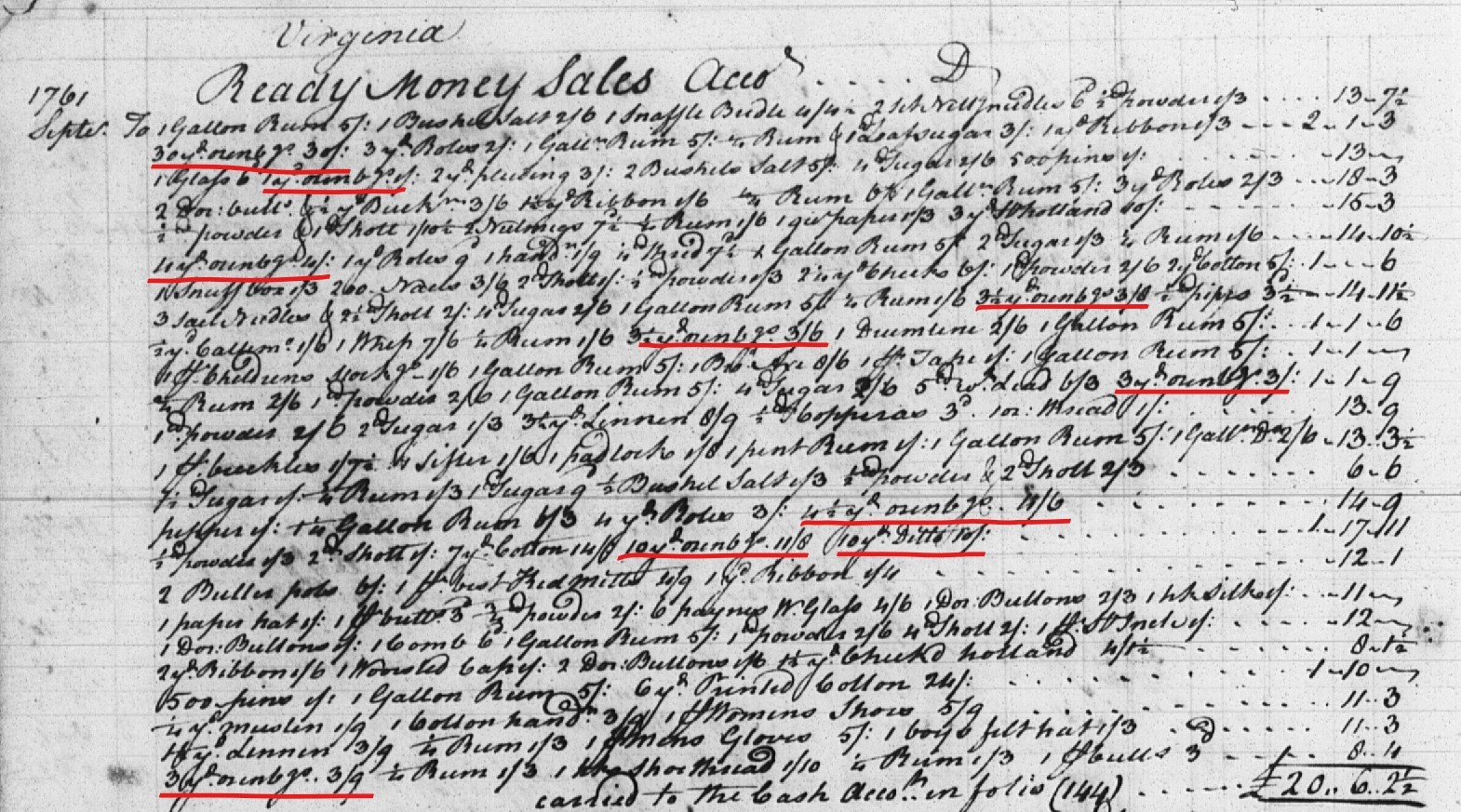

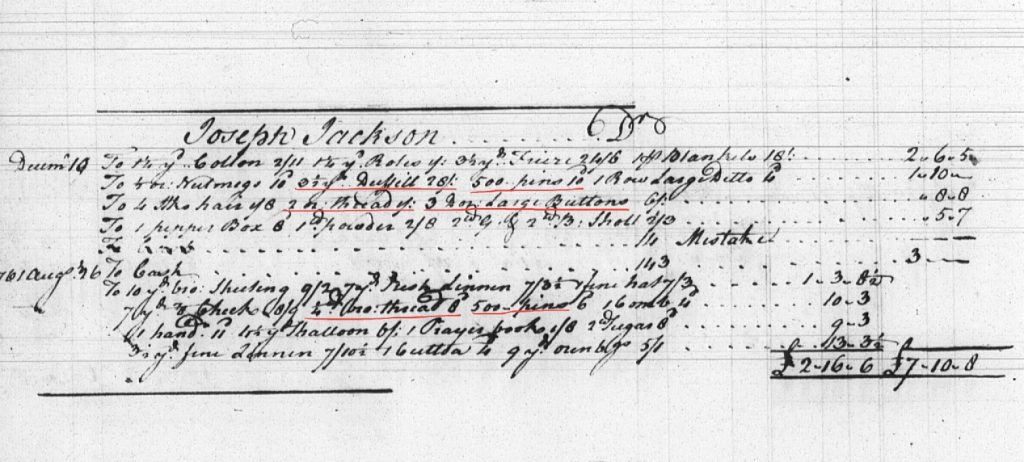

Jackson seemed to be quite an enigma when my initial research began. His purchases were what I presumed very similar to that of a tailor. I discovered his purchases often consisted of a mix of items such as pins, thread, and “duffils.”[1] These items drew me into exploring what this man truly intended to do with these objects.

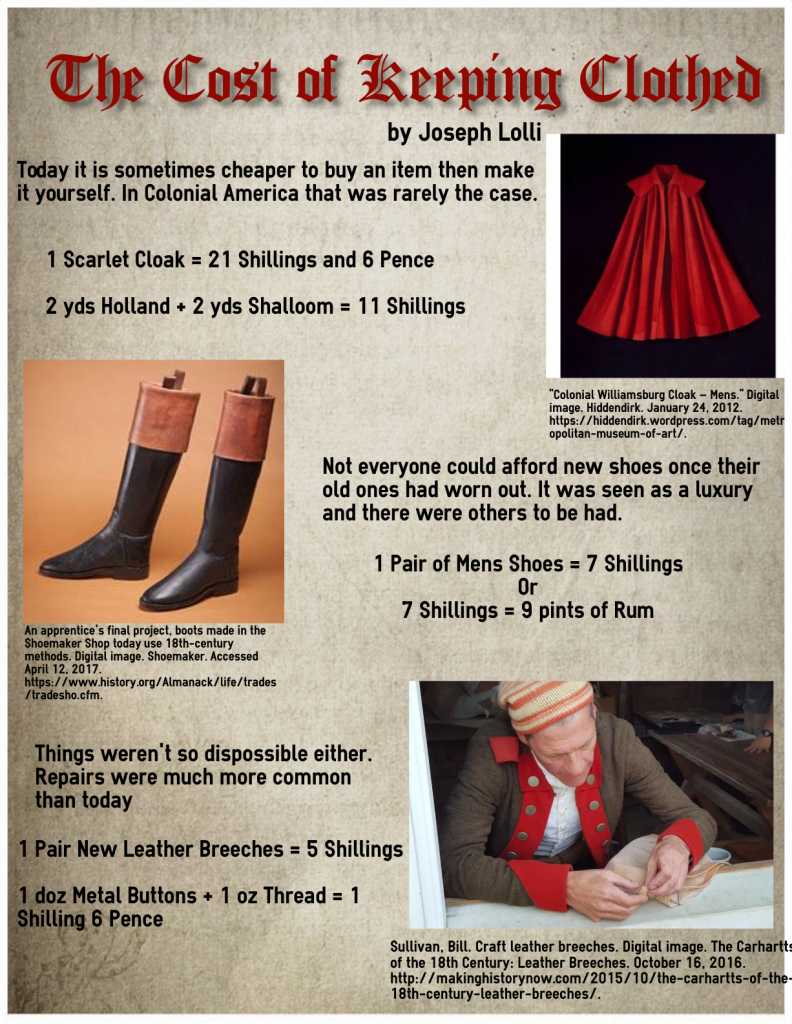

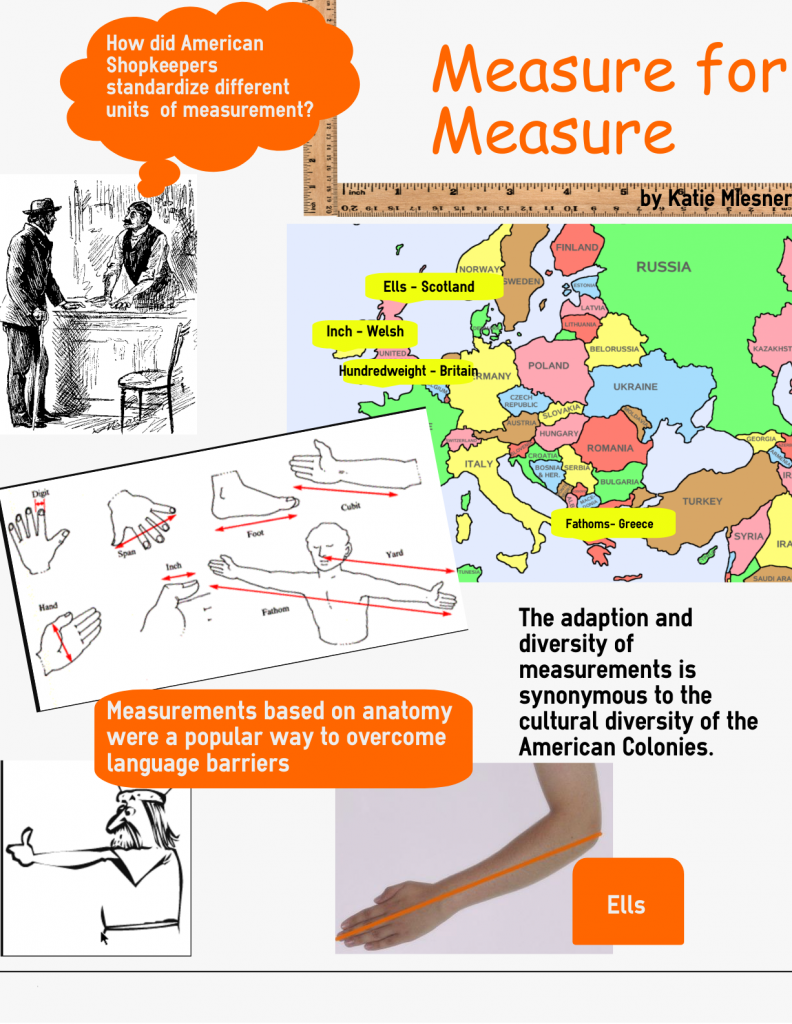

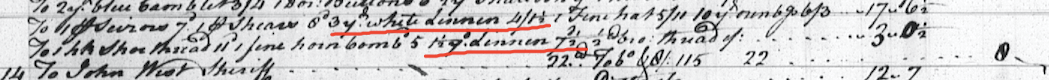

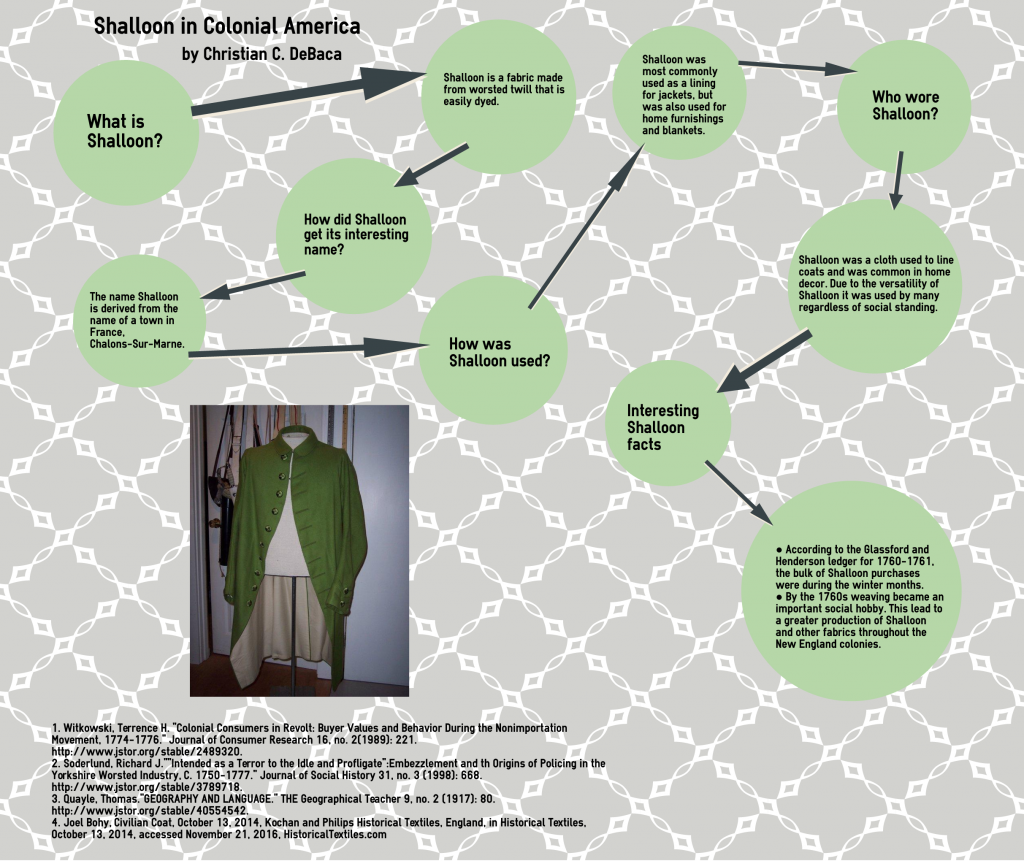

Now, it was no surprise that needles and threads could be used by a tailor, but duffil, or duffle, was a foreign fabric type with which I was not previously familiar. I researched the word and discovered what it was. I found duffle’s origin derives from the name of a Belgian town that crafted the fabric. It is a heavy, wool fabric that was first manufactured during the seventeenth century.[2] With this in mind, it led me to think about the use of the material.

Since Jackson bought the heavy fabric in December, it is possible he could have used the material to make a coat for himself or for another person to keep warm during the winter. The purchasing of duffle was not exclusive to one kind of trade and therefore did not provide conclusive proof of his profession. Moreover, these items could also have been purchased for another person, even a family member. The fact remained that if Jackson was not a tailor, then what (or who) were these purchases specifically for?

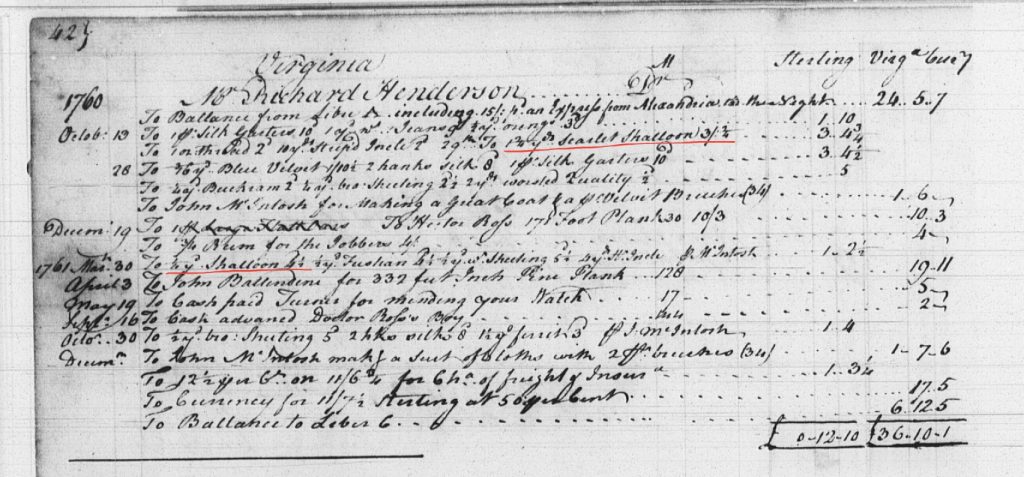

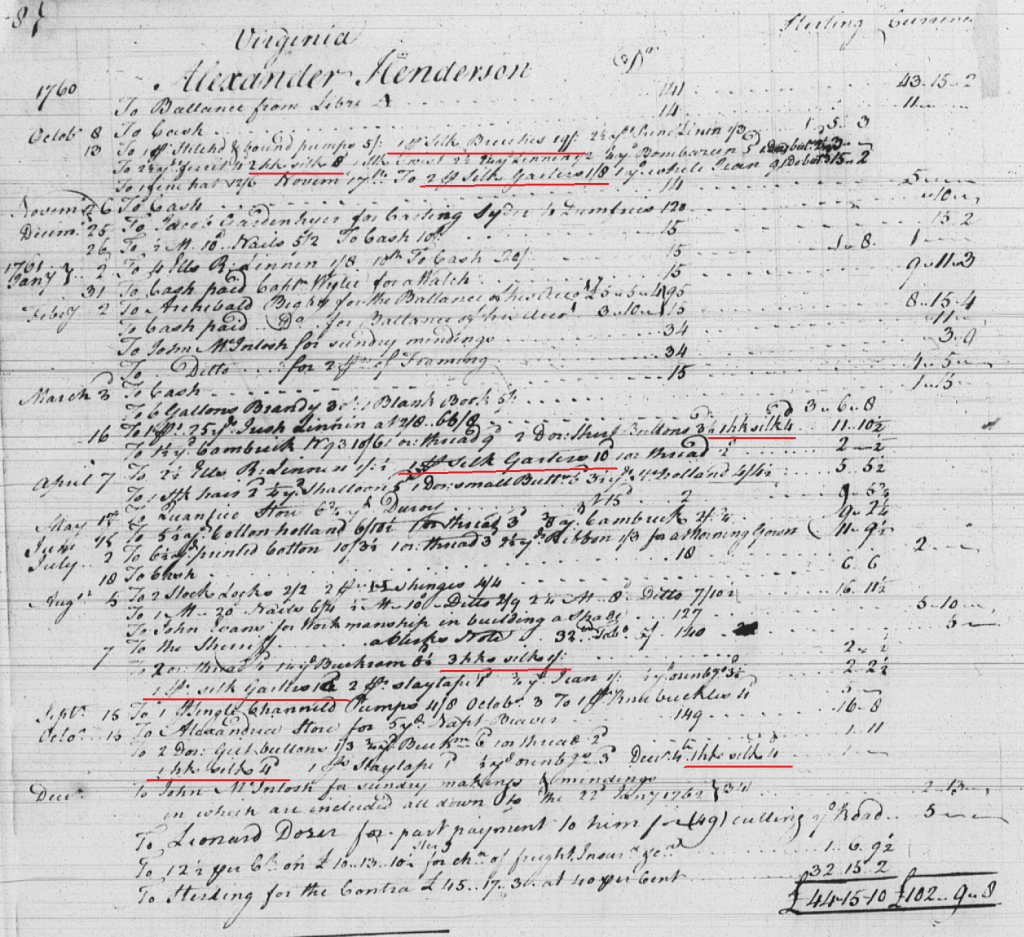

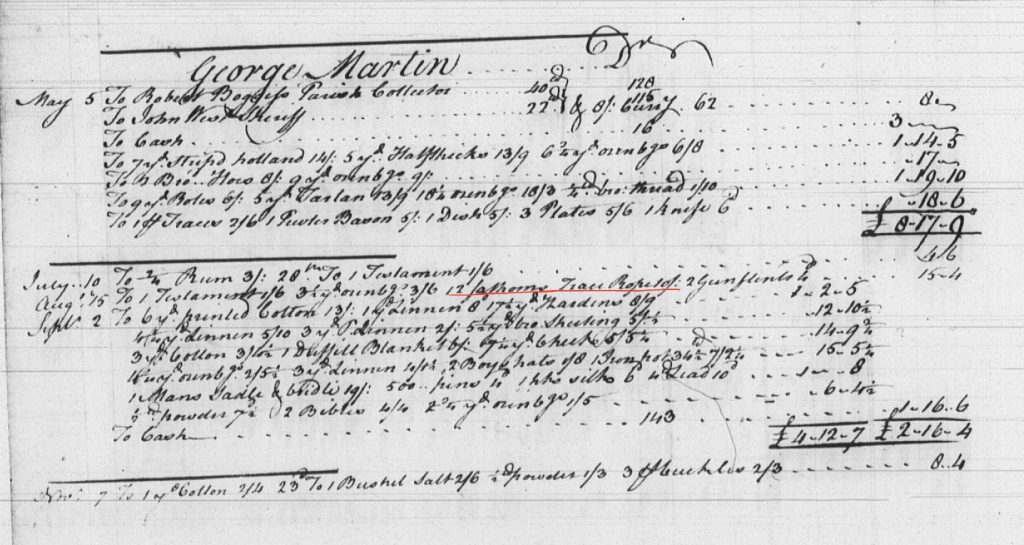

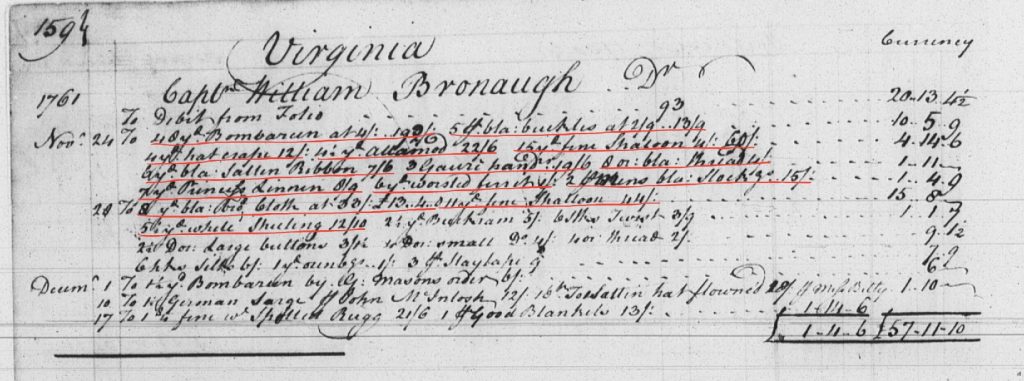

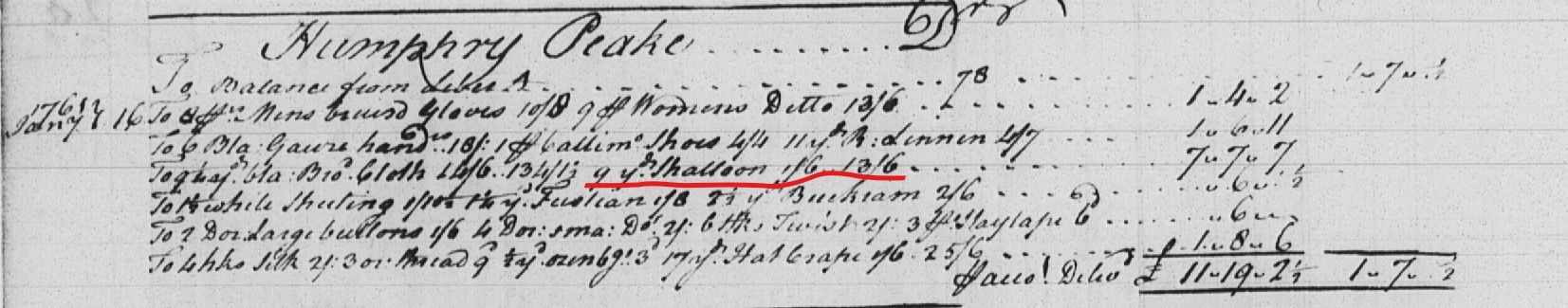

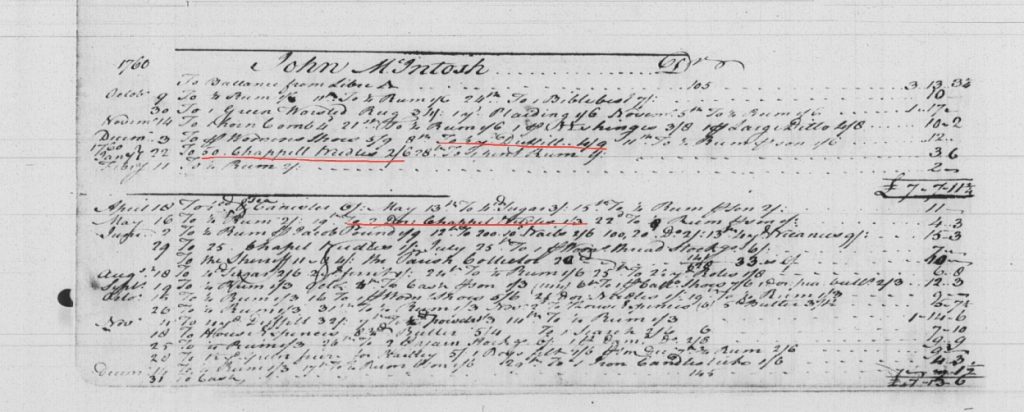

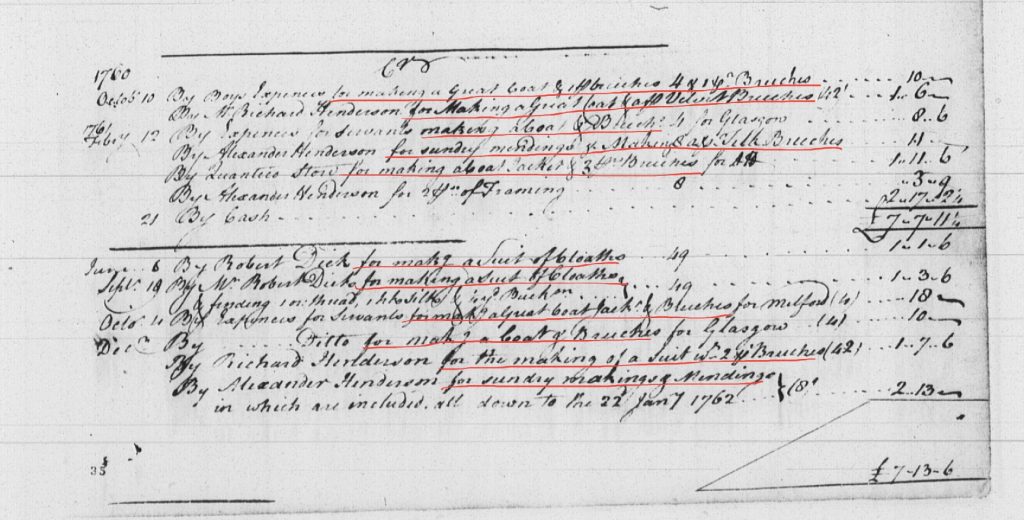

I realized that it was imperative to continue my investigation of Jackson’s purchases to discover the truth behind his identity. As I continued my analysis of Jackson’s account, I attempted to compare documents with another customer that I stumbled across. This individual, like Jackson, acquired similar items. This person was John McIntosh who was more likely to be a tailor based on how he paid his accounts – in the creation and repairs of clothing for Alexander Henderson (the Colchester store manager) and those enslaved by the store.[3]

Through McIntosh, I saw some similar purchases: needles and duffle. Knowing that McIntosh purchased his materials at the same store that Jackson did made me wonder if there were any connections. Given the similarity in purchases, perhaps Jackson was a tailor not yet employed, or perhaps he was an apprentice for a tailor and associated with McIntosh on some level. Yet, it was not enough evidence to surmise Jackson’s profession and it continued to be unknown to me. Whatever profession Jackson pursued was not clearly identified by his purchases alone and would take additional research to learn.

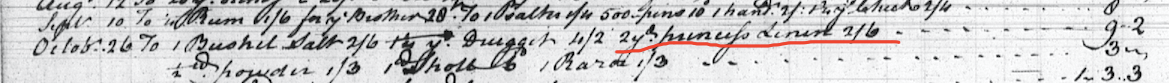

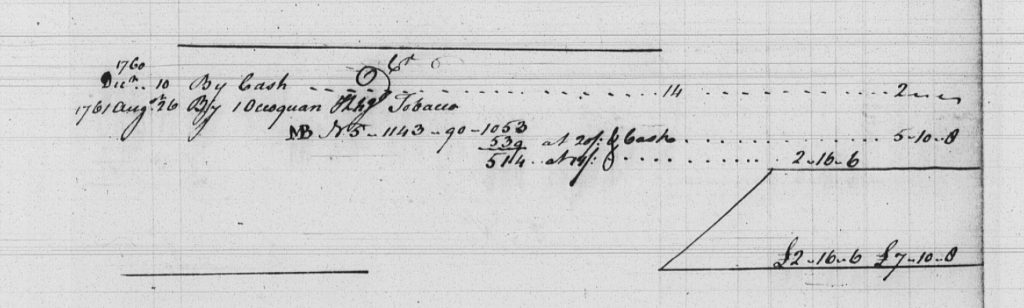

By looking at Jackson’s payments to the Colchester store, it became clear he was not a tailor at all.[4] He may have been connected to Marmaduke Beckwith (a landholder in the western part of Fairfax County) as Jackson’s credits came from selling tobacco notes originally belonging to Beckwith. Was Jackson a tenant of or farm manager for Beckwith? Although I couldn’t confirm what Jackson’s profession may have been by looking at his purchases, by continuing to look at Jackson’s accounts in full, I learned I was wrong in my initial interpretation of him as a tailor based on his fabric purchases and that sometimes it is hard work being a historian!

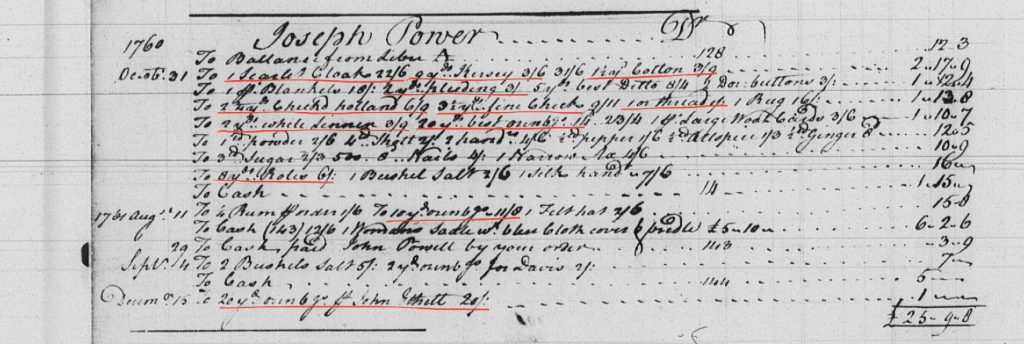

[1] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 117 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[2] “Duffle coat,” Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, accessed March 23, 2017, http://angelasancartier.net/duffle-coat.

[3] Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, folio 34 Debit.

[4] Ibid., folio 117 Credit.