Casey Wolf // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

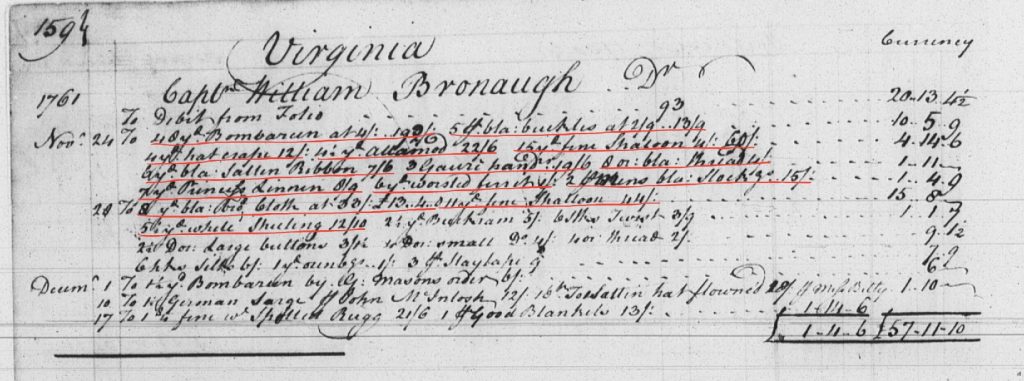

On 22 November 1761, death had come to the Gunston Hall Plantation in Fairfax County, Virginia. The deceased was Sempha Rosa Enfield Mason Dinwiddie Bronaugh—mother to Captain William Bronaugh and the daughter of George Mason II.[1] Prior to marrying Jeremiah Bronaugh, she was the widow of John Dinwiddie—a successful merchant on the Rappahannock River and brother of Robert Dinwiddie, Virginia’s lieutenant governor from 1751 to 1758.[2] In the days following her death, Captain William Bronaugh visited Alexander Henderson at his Colchester store to purchase items to begin the process of burial and mourning: bombasine, black buckles, crape, alamode, fine shalloon, black satin ribbon, linen, worsted ferret, black stockings, black thread, handkerchiefs, sheeting, and ties.[3] Much as in life, the purchase and display of material goods would proclaim the wealth and status of the well-born, well-bred, and well-connected Sempha Rose. So, how were material goods used to part with the dearly departed?

Unlike death, the practices and processes of confronting it in eighteenth-century colonial America are not certain. Partially informed by fashions and traditions from England, funeral and mourning customs were shaped by local factors as well. As a result, customs varied significantly throughout colonial America.[4] These variations reflected aspects of the colonists who participated in them.

For the dead

In the eighteenth century, the deceased were not often buried in their clothes as clothing was both laborious to make and a significant expenditure. Clothing in colonial America was often passed down to and altered for younger generations of a family. Instead, most people were buried in shrouds. Shrouds were robes split down the back with ribbons or strings at the openings for the hands and the feet, essentially enclosing the deceased within the shroud. The quality of the shroud and the material of which it was made depended on the wealth of the deceased.[5] Sempha Rose’s shroud was most likely constructed with the sheeting and tied with the twists that Bronaugh purchased. Rough cheap fabrics were used when burying the poor while higher quality fabrics—embellished with ruffles or pleats—were used to inter the wealthier. For those who needed to be buried promptly or who did not have a family to attend to their burial, winding sheets—usually of osnaburg—were wound around the body before it was placed into the grave.[6]

For the living

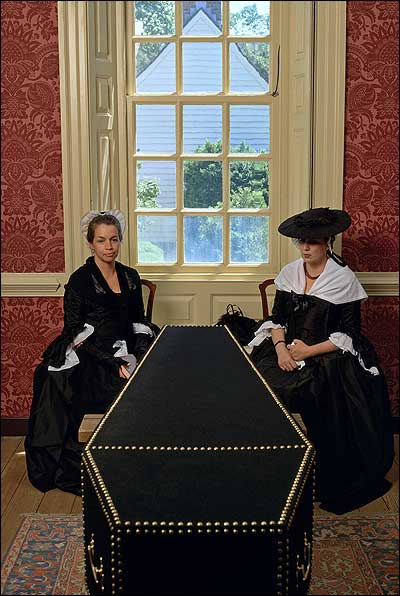

Many colonists wore specific outfits to outwardly express their feelings of grief and mourning. Although varied, mourning clothes were plain, usually consisting of dull material without embellishment.[7] Trimmed with white linen or black crape, dresses were made of bombasine—a blend of wool and silk—with either button or black ribbon closures.[8] On the head, hoods, veils, caps, or any combination of the three were made of and embellished with crape and silk.[9] Accessories included handkerchiefs or fans.[10]

For men, mourning suits were made of woollen material most likely broad cloth, shalloon, or a combination of the two—with crape wrapped around the band of the hat.[11] Depending on the wealth of the family, servants would also receive mourning clothes—although of lesser quality and often only a few pieces. Bronaugh’s order of materials already dyed black are a statement of his wealth. The wealthy could afford to have a set of clothes made specifically for mourning purposes while the poor dyed their everyday wear to serve as mourning clothes.[12]

As the development of Atlantic trade facilitated easier means of exchange between Europe and the colonies, colonists began to use displays of material goods to project declarations of wealth traditionally limited to the wealthy.[13] Mourning materials made available to increasingly wealthier colonists allowed them to participate in traditions previously reserved for European aristocracy.[14]

[1] Michele Lee, “Simpha Rosa Ann Field Mason,” George Mason’s Gunston Hall, last updated May 18, 2011, accessed March 23, 2017, http://www.gunstonhall.org/library/masonweb/p1.htm#i8.

[2] Pamela C. Copeland and Richard K. McNaster, The Five George Masons: Patriots and Planters of Virginia and Maryland (Fairfax County, VA: George Mason University Press, 2016), chap. 2.

[3] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 159 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association); History Revealed, Inc. Glassford and Henderson glossary.

[4] Kelly Arehart, interview by Harmony Hunter, “The Business of Death,” Past & Present (MP3 broadcast), Colonial Williamsburg, uploaded March 30, 2015, accessed March 23, 2017,

http://podcast.history.org/2015/03/30/the-business-of-death/.

[5] Arehart and Hunter, “The Business of Death.”

[6] Ibid.

[7] Kirstin Olsen, Daily Life in 18th-century England (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing, 1999), 108.

[8] Linda Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America, the Colonial Williamsburg Collection (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002), 177-78;

Lou Taylor, Mourning Dress: A Costume and Social History (New York, NY: Routledge, 1983), 78.

[9] Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal, 177; Taylor, Mourning Dress, 78, 81-2.

[10] Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal, 180; Taylor, Mourning Dress, 82.

[11] Taylor, Mourning Dress, 78-9.

[12] Olsen, Daily Life, 108.

[13] Lorena S. Walsh, “Urban Amenities and Rural Sufficiency: Living Standards and Consumer Behavior in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1643-1777,” The Journal of Economic History 43, no. 1 (March 1983): 117.

[14] Taylor, Mourning Dress, 78.