Luis Torres Rivera // AMH 4112.001 – The Atlantic World, 1400-1900

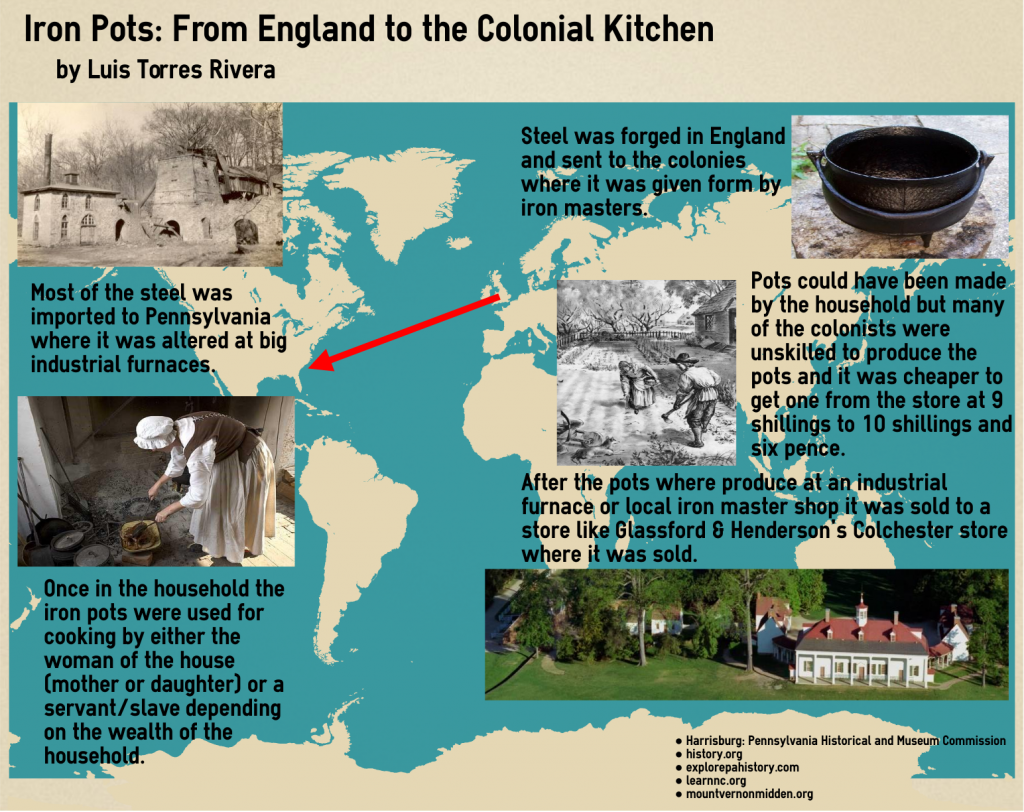

Iron pots were in use in the 1700s. They were used to cook over an open fire given that iron is one of the best transmitters of heat. “During the late seventeenth century and the early eighteenth century, Pennsylvanians imported most of the iron that they used from Britain.”[1] Given that iron ore was mostly imported to the colonies, “ironmasters established early furnaces and forges as a more efficient way to make more iron than local blacksmiths were able to, and as a way to make profits and to diversify their investments.”[2] Iron pots may have been manufactured either in a large industrial furnace or by a local blacksmith. In Virginia, Thomas Jefferson described iron manufactured from two furnaces as being exceptionally strong: “Pots and other utensils, cast thinner than usual, of this iron, may be safely thrown into, or out of the waggons in which they are transported.”[3] They were thinner than usual due to that in “1750 the British government enacted the Iron Act which prohibited the erection of new steel furnaces, mills for slitting or rolling iron and plating forges with tilt hammers,” so that jobs would not be stolen from British citizens.[4]

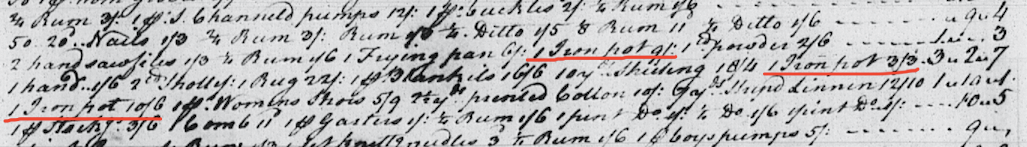

At Glassford and Henderson’s Colchester, Virginia store, we see the sale of iron pots as part of the Ready Money accounts in 1760-1761. In November 1760, three iron pots were sold with prices ranging from 9 shillings to 10 shillings and six pence.[5] In other months like August, April and December iron pots were sold at similar prices. The small variation of prices could be presented in regards of the quality and thickness of the iron used. Also, sales could have been greater in November in preparation for the winter season.

Looking at the conditions in colonial times, the iron pot was a commodity necessary to the household. “While theoretically, colonists could have manufactured all their own high quality consumer goods and accumulated a valuable a stockpile as that of the person buying on the market, it would be rather unlikely that the nonspecialized home manufacturer could have shone in all areas of production. In fact, most homemade items tended to be crude and cheap.”[6] Iron pots were hard to make; they were sold in local stores or by blacksmiths that had furnaces to make them. As seen in the Colchester store, iron pots were valuable and necessary commodity.

[1] Arthur C. Bining, Pennsylvania Iron Manufacture in the Eighteenth Century (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission), 1973.

[2]Ibid.

[3] Thomas Jefferson, “QUERY VI A notice of the mines and other subterraneous riches; its trees, plants, fruits, &c.”, Notes on the State of Virginia, http://xroads.virginia.edu/~HYPER/JEFFERSON/ch06.html (Accessed on 18 April 2016).

[4] Harold B. Gill, Jr. The Blacksmith in Colonial Virginia. (Williamsburg, Virginia: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1965), (Accessed 5 December 2016), http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/View/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports%5CRR0022.xml.

[5] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia Folio 10 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[6] Carole Shammas , “Consumer Behavior in Colonial America,” Social Science History 6 (1982): 67–86, 81.