Jeremy M. Bell // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

If you had a hogshead, what would you do with it? Would you drink out of your hogshead? How about pack it full of tobacco to save for later? Would you pack it full of sugar maybe? Well, if you were living in colonial America you certainly might do any of the above.

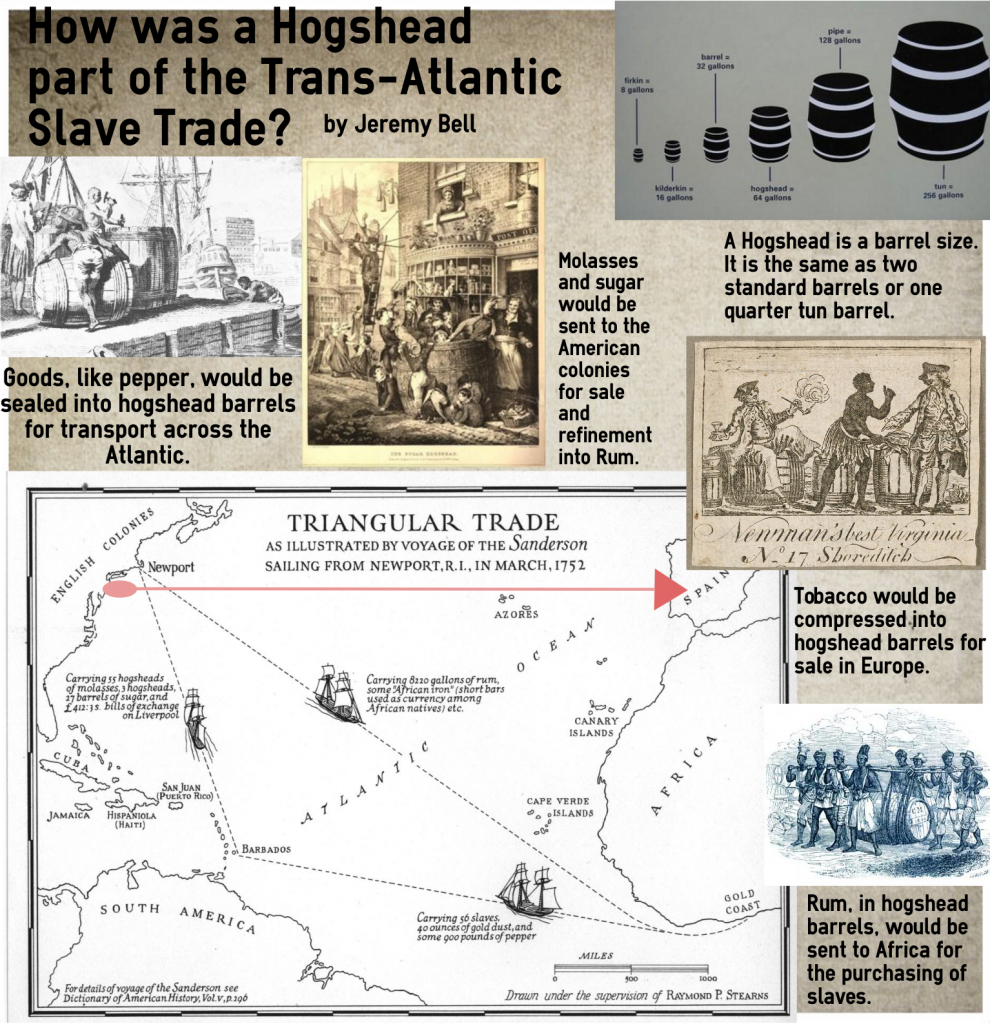

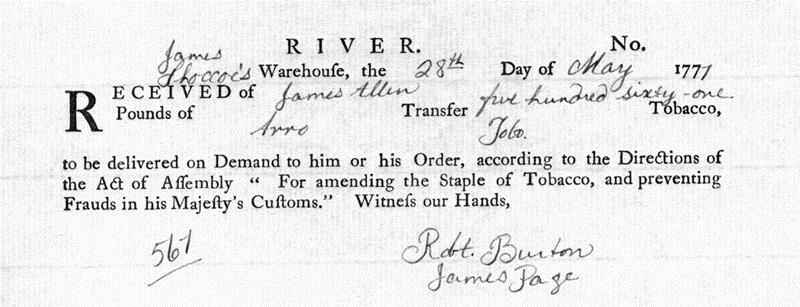

A hogshead is a unit of measurement used more commonly in colonial times than today. And why is that? The easy answer is that the average person today does very little with barrels. In colonial times, when you entered a store one of the first things to be noticed was the number of barrels present. Barrels were the shipping containers of their time. For ease of transport, storage, and sealable freshness, barrels were the colonial Tupperware. So, what constitutes a hogshead, and where does the term come from?

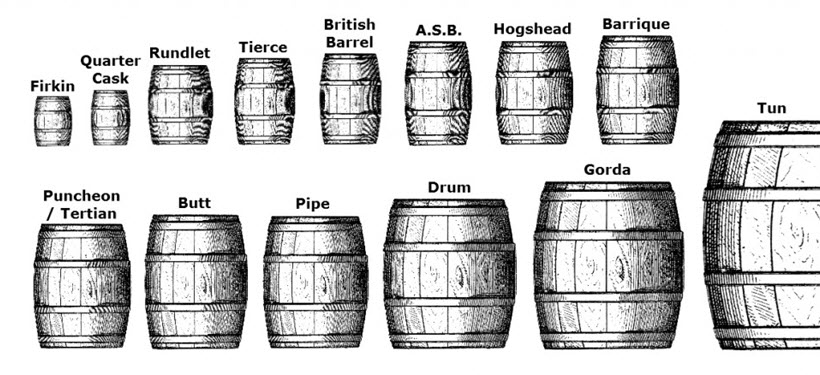

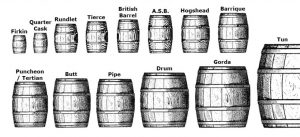

In 1423, the British Parliament passed the first act to standardize barrels and their measurements.[1] A tun was set at 252 gallons. Each designation of volume would then be cut in half. So, a pipe barrel would be measured as 126 gallons, or half of a tun. Following suit, a hogshead would measure in at 64 gallons and a standard barrel at 32 gallons.[2] There were exceptions to the halving rule, and more barrel sizes, but these were the main units of measure. Dry goods, such as tobacco, sugar, or salted fish, would be packed into the barrels until the net weight matched that of the same barrel full of water, to help standardize weight measurements.[3]

The etymology of the term hogshead was clarified by Walter William Skeat of Cambridge in 1896. The term ‘hogshead’ was traditionally believed to be derived from hog’s hide, a possible material for containers to hold wine. Skeat argued that this simply wasn’t so. Tracing the term through the Dutch, Swedish, and Danish languages, Skeat argued that in all other languages, the first part of hogshead refers to an ox, not a hog. He concluded that hogshead was a corruption of the Swedish word oxhuvud meaning both the head of an ox and a barrel.[4]

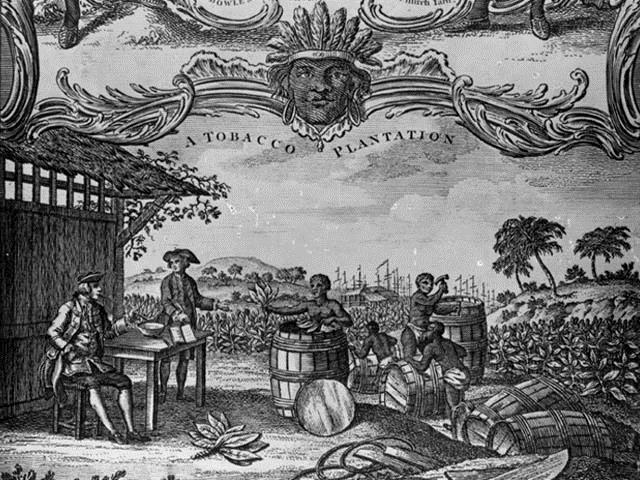

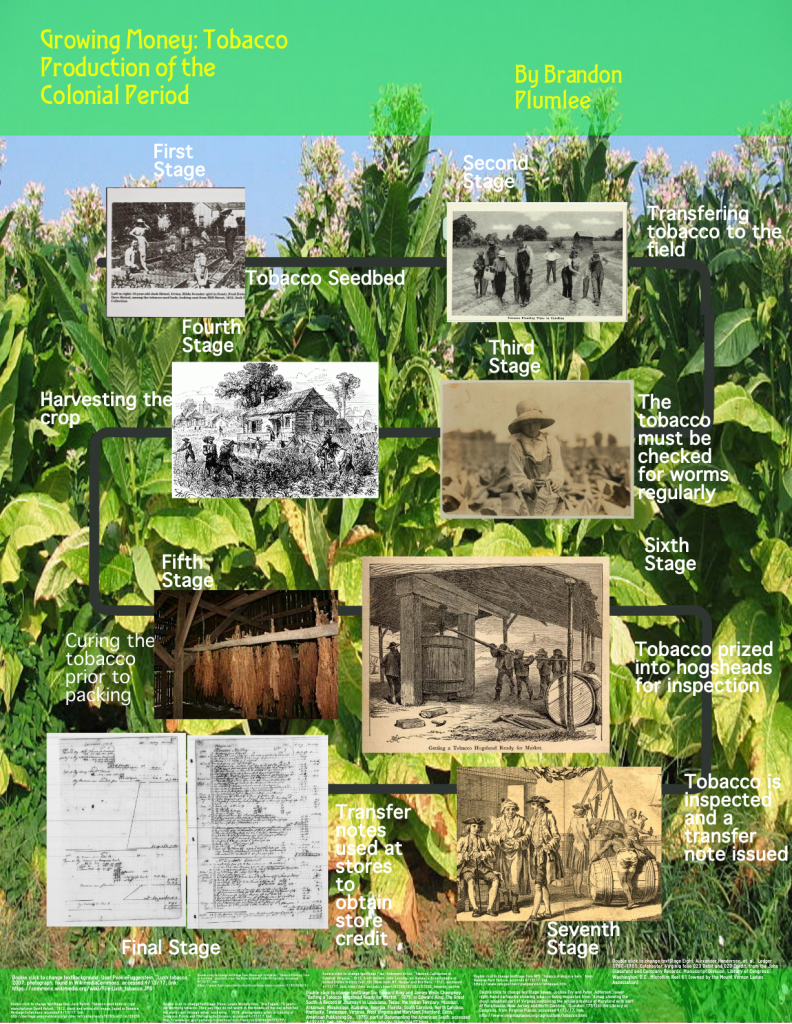

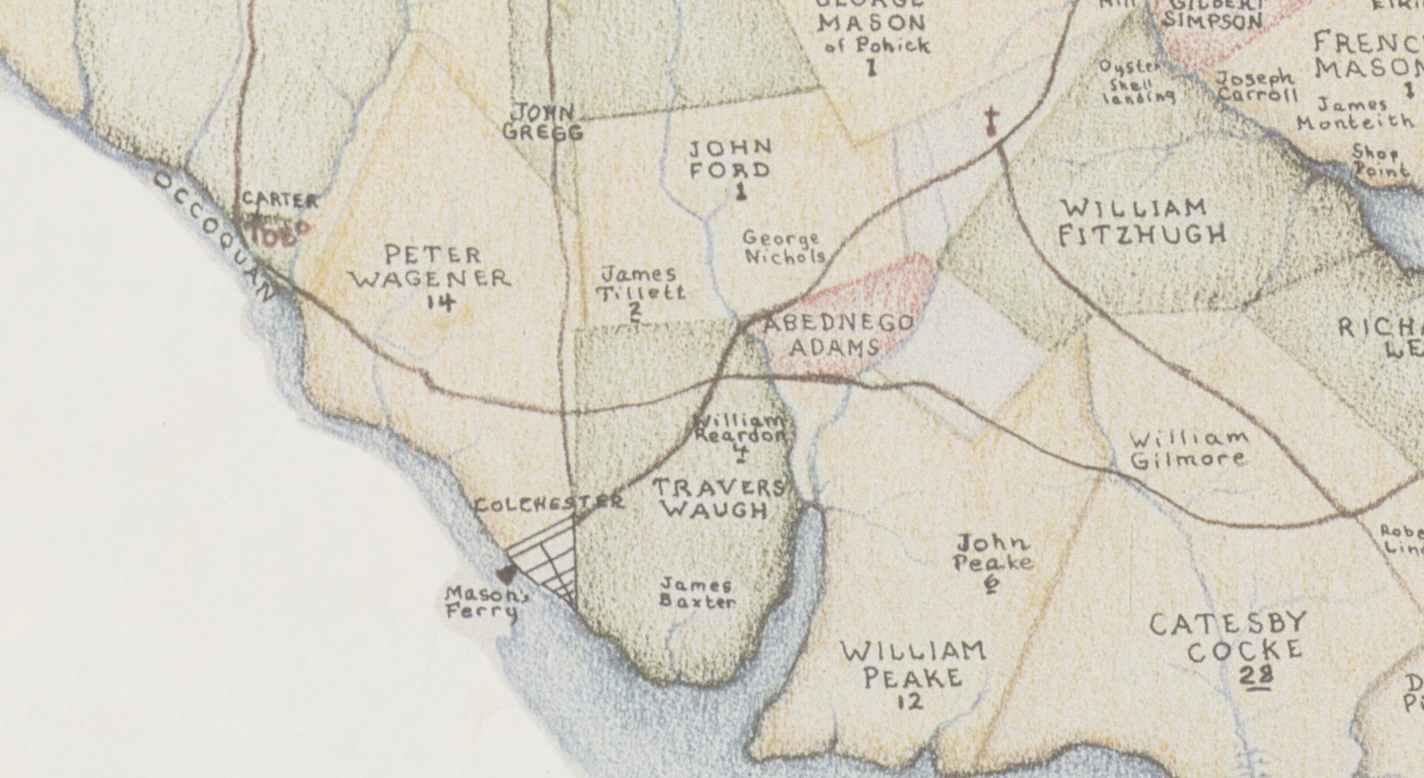

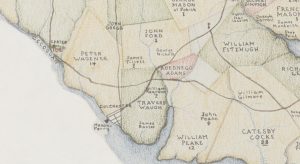

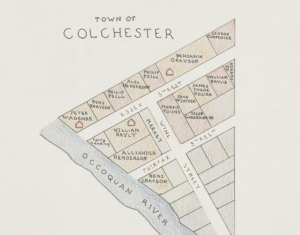

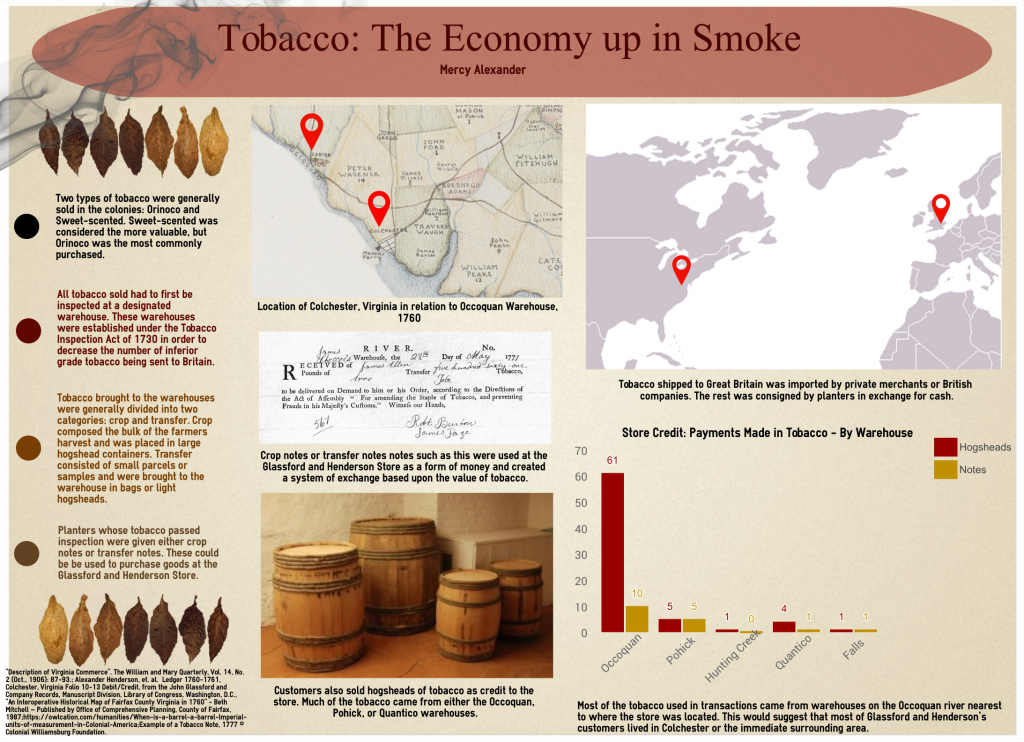

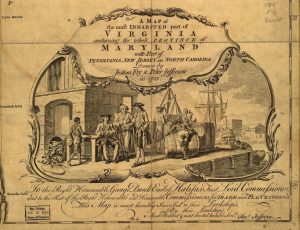

A hogshead barrel would have been a common sight in colonial American stores like that of eighteenth-century shopkeeper Alexander Henderson, factor for John Glassford, at the Colchester store in Virginia. John Glassford was one of the most prominent Scottish tobacco lords until his death in 1783.[5] The Glassford Company was the second highest shipper of hogsheads of tobacco to Great Britain in 1774 importing 4,506 hogsheads.[6]

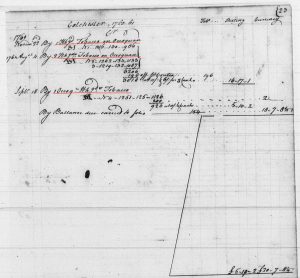

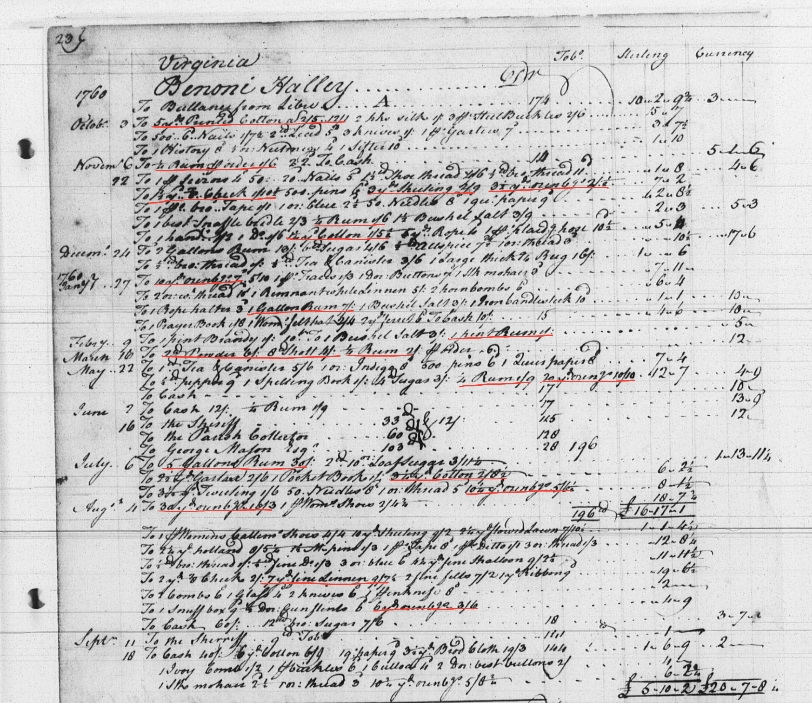

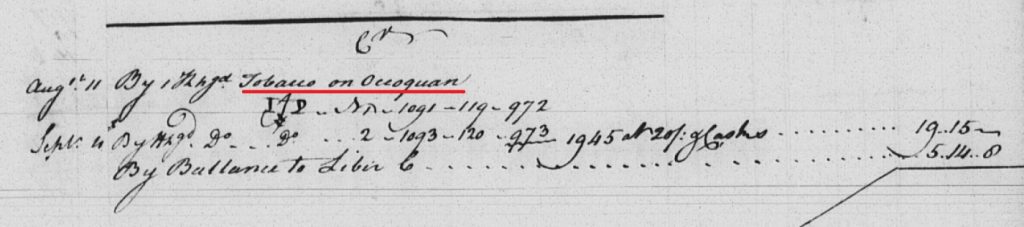

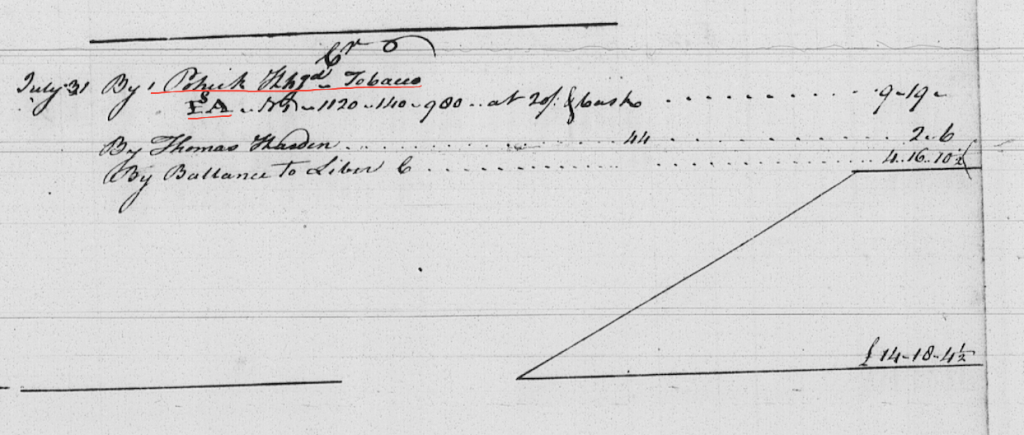

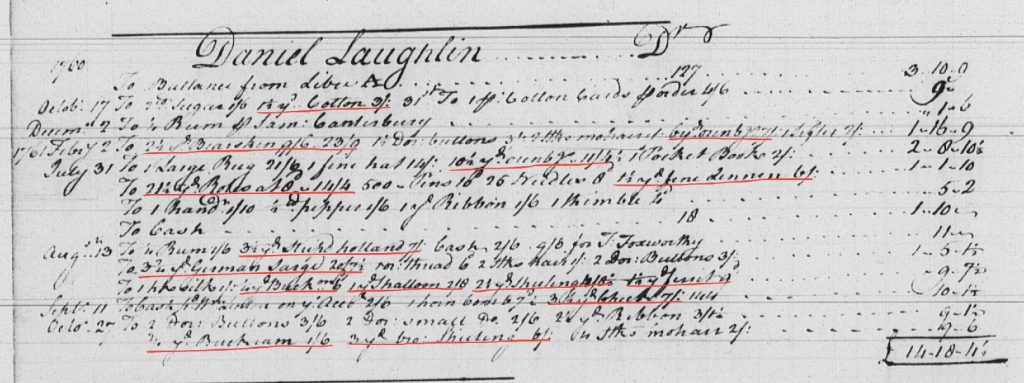

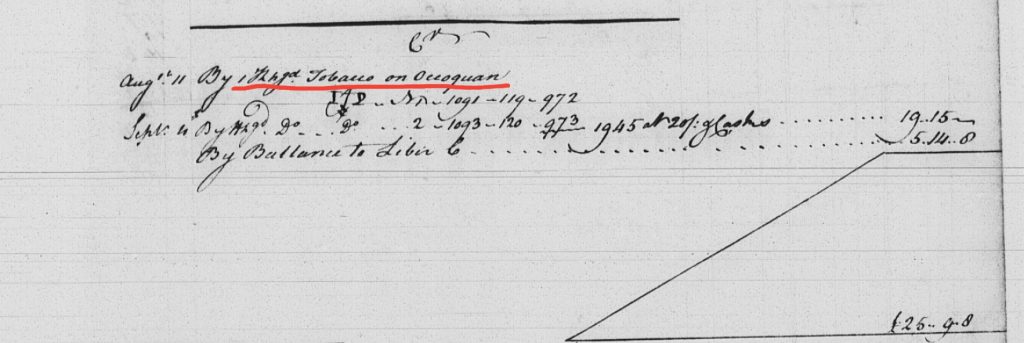

It was through the transcription of the 1760/1761 Colchester ledger that I first came across hogsheads. One of the ways in which customers could receive credit was through the selling of tobacco contained in a hogshead. Tobacco was the most common form of payment in the store.

Abbreviated in the ledger as Hhd or Hhds, a hogshead is still used in the wine and whiskey markets mainly for maturing alcohol.[7] While less common today, this unit of measure and the container it refers to was an element of everyday life in colonial times. From the common mercantile store to large plantations, a hogshead barrel was an essential element of life before and after its standardization by the British Parliament in 1423.

[1] United States, Department of State, “Report upon Weights and Measures,” John Quincy Adams, Senate 119 and House 109 of 16th Congress 2nd Session, Boston Public Library (Washington: Printed by Gales & Seaton, 1821), 27, https://archive.org/details/reportuponweights1821unit.

[2] Department of State, “Report,” 27.

[3] Ibid., 26.

[4] William Walter Skeat, A Student’s Pastime: Being a Select Series of Articles Reprinted from “Notes and Queries” (London, England: Clarendon press, 1996), 33.

[5] John Francis Hackett, John Glassford and Company Records: A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 2000), 4.

[6] James H. Soltow, The Economic Role of Williamsburg (Williamsburg: University Press of Virginia, Charlottesvile, 1965), 47, Colonial Williamsburg Digital Library,

http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/view/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports\RR0066.xml&highlight=.

[7] “Casks (barrels, hogsheads, butts),.” WhiskyInvestDirect, accessed April 20, 2017,

https://www.whiskyinvestdirect.com/about-whisky/scotch-whisky-casks-and-barrels.