Griffin Bixler // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

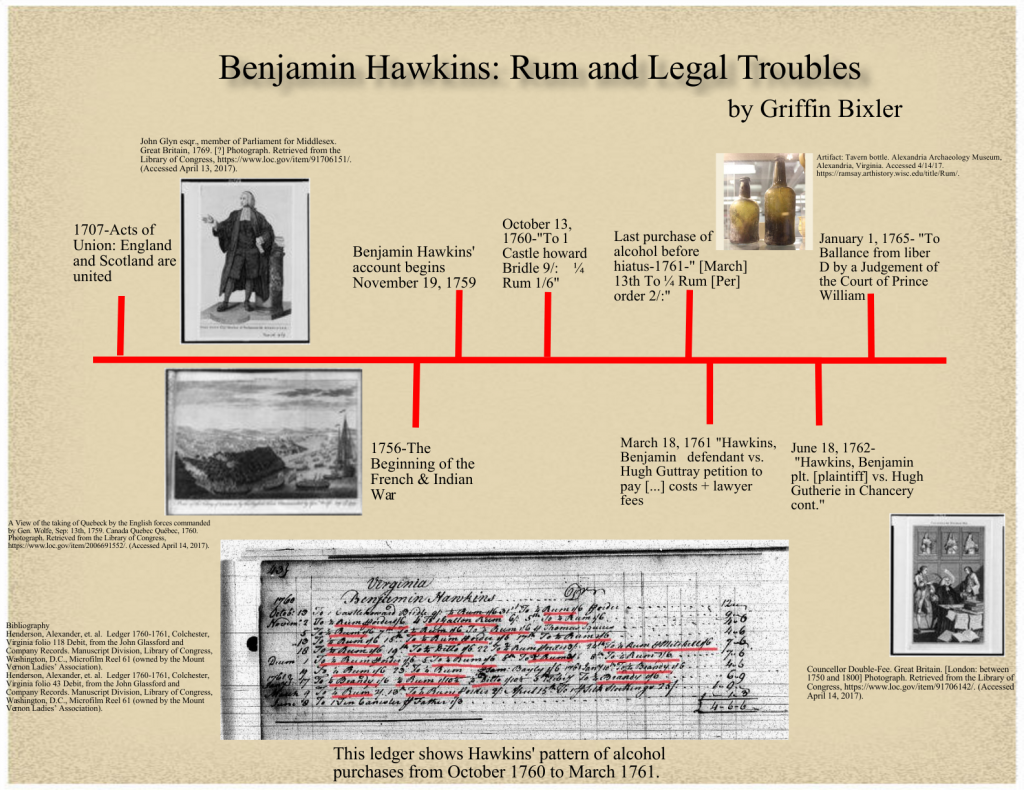

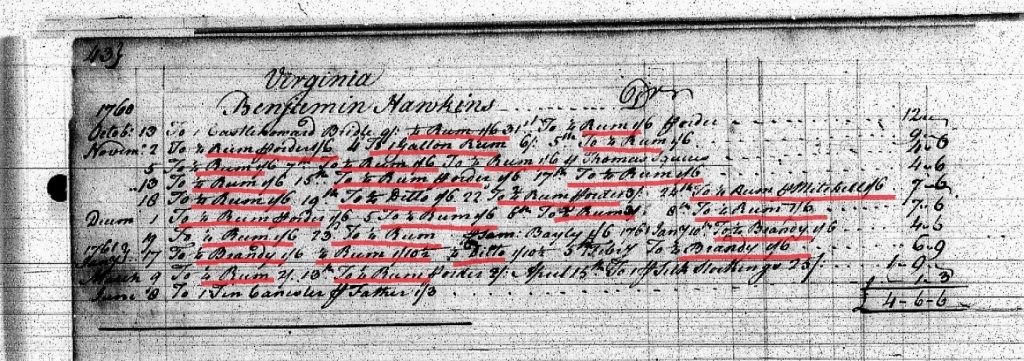

In the mid-eighteenth century, several stores in Fairfax County, Virginia, were owned by two men, John Glassford and Alexander Henderson. Their store ledgers contain vast amounts of information about their customers, their credit, and the goods they bought. One interesting case within the ledger for the Colchester store (1760-1761) was Benjamin Hawkins, who purchased rum frequently from October 13, 1760, to June 8, 1761.[1] His purchases were a product of the changing economic environment that occurred around this period.

For colonists in the Chesapeake, alcohol was an important part of life. Colonists consumed alcohol at every meal, during church, at social gatherings, and on numerous other occasions.[2] Early in the eighteenth century, colonists acquired alcohol through producing it at their household or buying it from planters and taverns.[3] By the mid-eighteenth century, the colonial economy expanded as a result of its connection to Britain and the rest of its empire.[4] Goods, such as alcohol, became cheaper and diverse. Colonists could purchase new variants of alcohol that were impossible or hard to create in the colonies.

One of these was rum. A great source of rum came from Scottish traders.[5] Previously, Scottish traders could not operate in the colonies because Britain limited colonial trade through the Navigation Acts of 1663.[6] The Navigation Acts forced colonists, among other things, to export profitable goods, such as tobacco and sugar, only to Britain.[7] In 1707, England and Scotland united, allowing Scottish traders to sell their goods in the colonies. In fact, this uniting provided John Glassford, who was Scottish, to become so successful in the Chesapeake through his numerous stores. Rum became increasingly popular with the lower classes with many of the lower classes enjoying rum for its fortitude in the hot Chesapeake climate and its cheap price. Rum, along with other alcohols, also lessened servants’ dependence on planters for drink.[8]

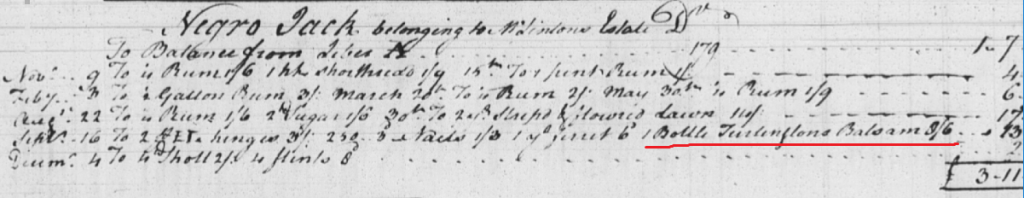

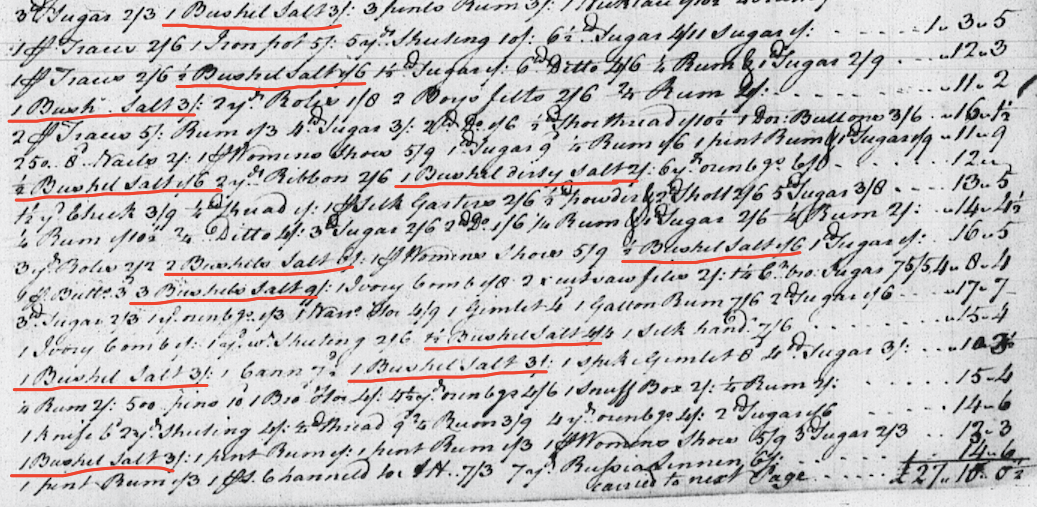

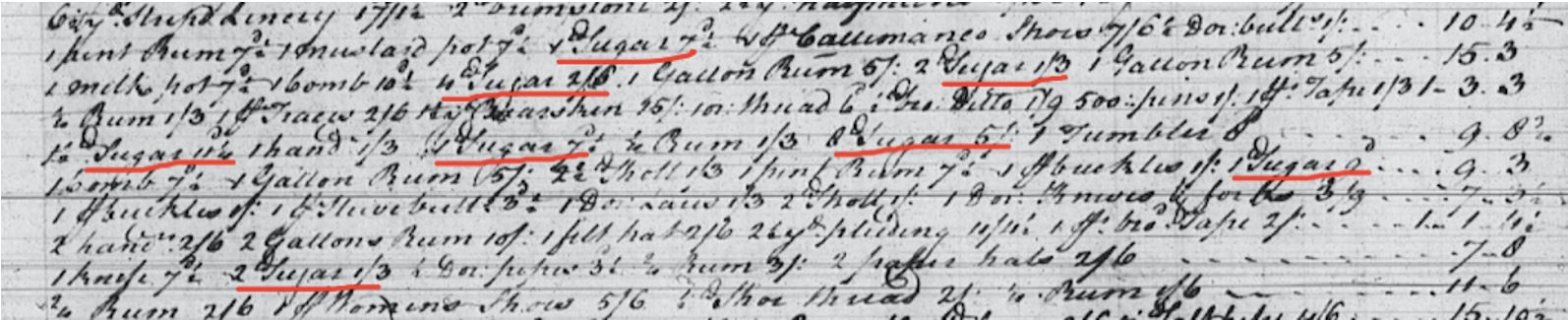

As mentioned earlier, the majority of Hawkins’ purchases were rum. His account shows that he purchased rum every couple of days through the month of November 1760. Hawkins mostly purchased rum one quart at a time, but there was an exception on November 4, 1760. On that day, Hawkins purchased a gallon of rum. The gallon of rum, according to the credit side of the account, was paid for in cash, although not in its entirety as the rum cost 6 shillings and Hawkins only provided the store 5. Hawkins returned the next day and purchased only “1/4 [one quart] Rum.”[9]

In all, he purchased seven gallons and two quarts of rum between October 13, 1760, and March 13, 1761. In addition to rum, Hawkins purchased brandy on several occasions (January 10, January 17, and February 5, 1761), a bridle (October 13, 1760), silk stockings (April 15, 1761), and a tin canister (June 8, 1761). The tin canister was the last purchase he made at the Colchester store in 1761.[10]

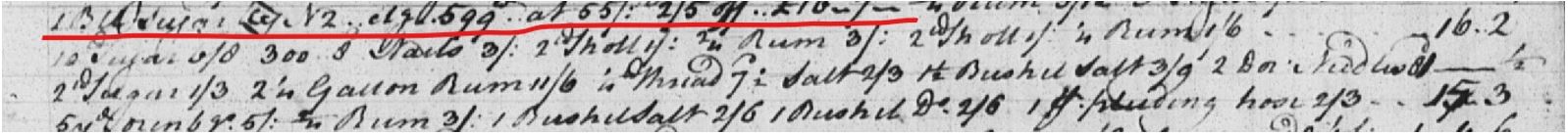

An interesting element that came up during research was Hawkins’s involvement in several court cases. It seems that Hawkins legally quarreled with a man named Hugh Guttray. Hawkins was a defendant in an injunction case in opposition to Guttray.[11] An injunction is a court order that a person is either allowed or not allowed to do something. He was also involved as a plaintiff in a chancery suit.[12] A chancery suit entails a matter of equity, such as a dispute over land or individual status.[13] These court cases occurred after the period when Hawkins purchased his rum from Glassford and Henderson’s store, but were the disputes a reason for Hawkins’s drinking? It is difficult to tell whether his drinking was exacerbated by the court cases. After a hiatus in his account, it resumed in January 1765. Now living in Augusta, Virginia, Hawkins had to pay court fees to Prince William County (adjacent to Fairfax County). On the credit side, it showed that the payment was moved “By Ballance to Liber F,” which meant Hawkins accrued the fees as a debt. Hawkins did not buy alcohol during this period.[14]

Benjamin Hawkins’ constant purchase of rum illustrates the changes that occurred in the colonial economy. Rum, and other accessible goods, became affordable to the colonists. His constant purchases of rum would have been inconceivable several decades earlier. The colonial economy was going through a “consumer revolution,” which facilitated the purchase of diverse goods at cheaper prices.[15]

[1] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 43 Debit, from the John Glassford and

Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the

Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[2] Sarah H. Meacham, Early America: History, Context, Culture : Every Home a Distillery : Alcohol, Gender, and

Technology in the Colonial Chesapeake, (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2009), 6.

[3] Meacham, Every Home, 82.

[4] Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settling of North America, (New York: Penguin Books, 2001), 310.

[5] Meacham, Every Home, 85.

[6] Taylor, American Colonies, 258.

[7] Ibid., 306.

[8] Meacham, Every Home, 82-87.

[9] Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, folio 43 Debit.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Fairfax Court Order Book 1756, page 572, March 18, 1761, Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center,

Fairfax, Va.

[12] Fairfax Court Order Book 1756, page 596, June 16, 1761, Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center, Fairfax,

Va.

[13] Fairfax County, Virginia, “Historic Records Finding Aids,” accessed April 19, 2017, http://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/courts/circuit/historical-records-finding-aids.htm

[14] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1765, Colchester, Virginia folio 38 Debit, from the John Glassford and

Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 59 (owned by the

Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[15] Taylor, American Colonies, 310.