Noelle Robison // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

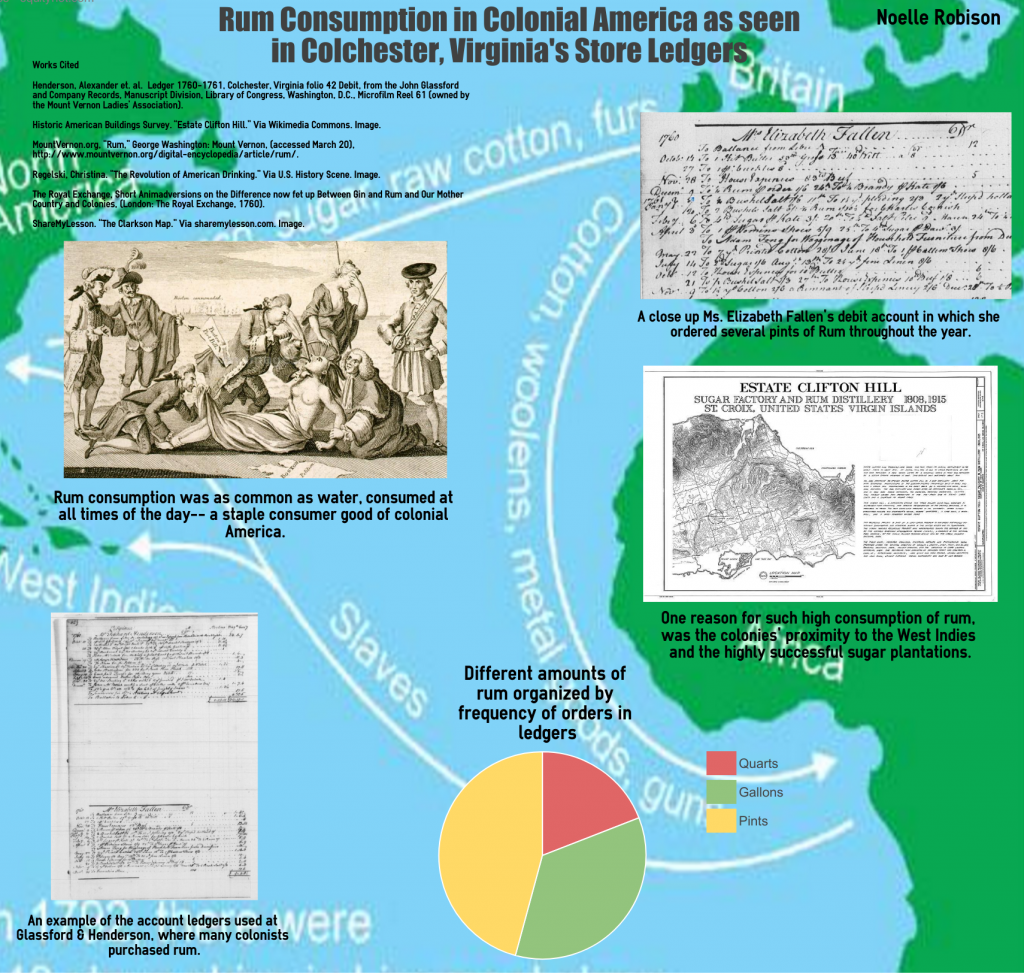

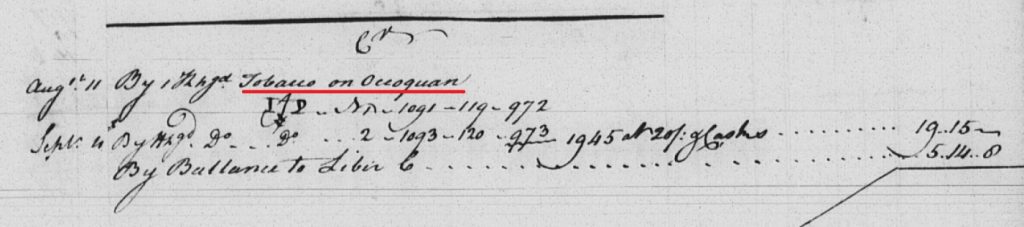

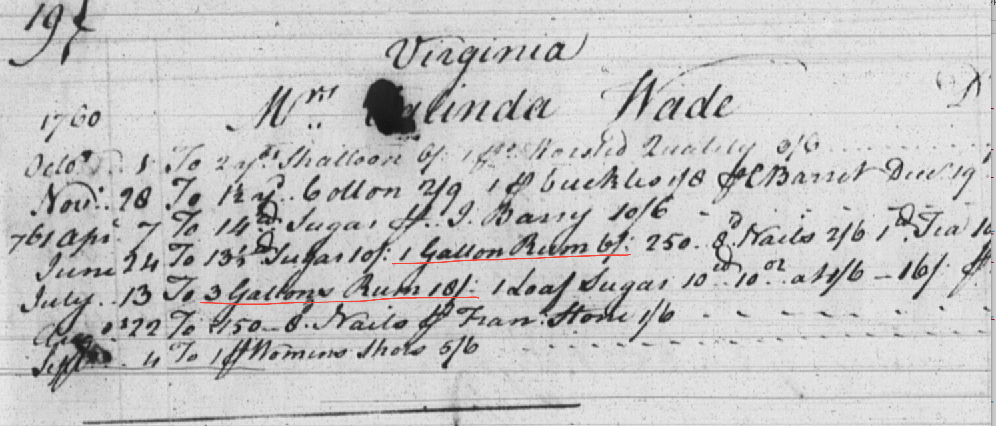

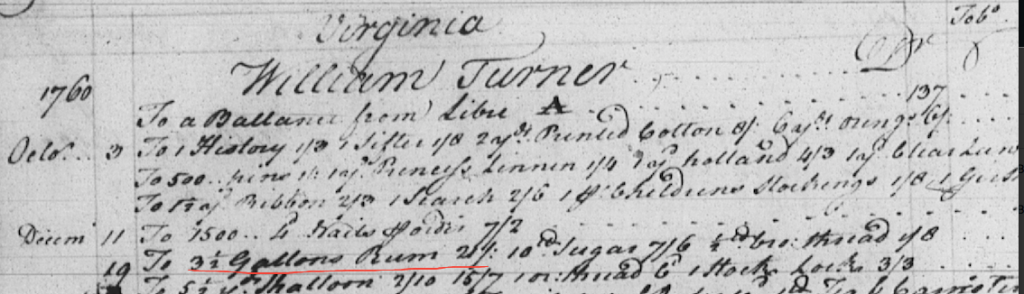

Alcohol, rum specifically, was consumed regularly and at all times of the day in the British colonies of North America. The Colchester store ledger from 1760-1761 in Fairfax, Virginia, shed light on this observation. Almost every account listed in the folios have entries regarding the purchase of rum. For example, in Valinda Wade’s and William Turner’s accounts, there are several entries with rum purchased by the quart and a few by the gallon.[1] Other folios, such as Benoni Halley’s account, show several gallons purchased in a short period of time.[2] William Scott also purchased many gallons.[3] In summation of the thirteen folios reviewed, a pattern of high rum purchases and consumption was realized. Rum was the alcohol of choice in the colonies largely due to its proximity to the sugar plantations in the Caribbean. It is estimated that the average colonist consumed 3.7 gallons annually.[4]

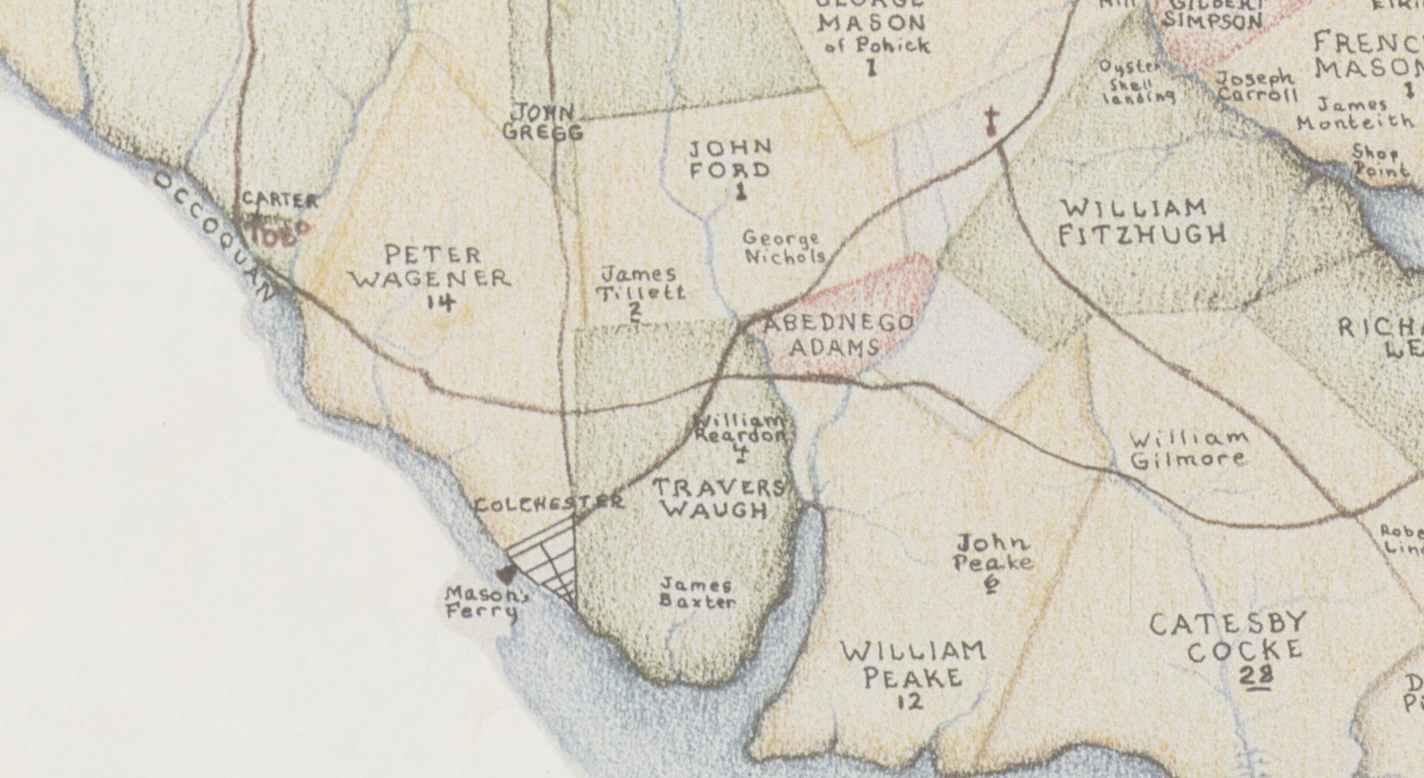

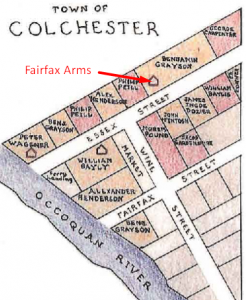

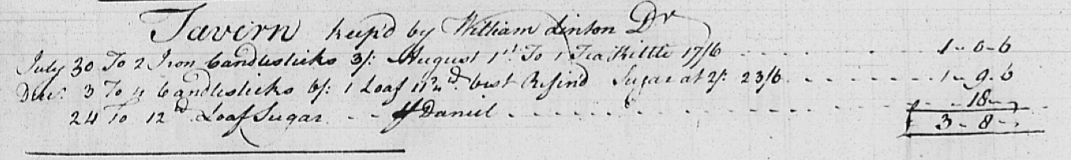

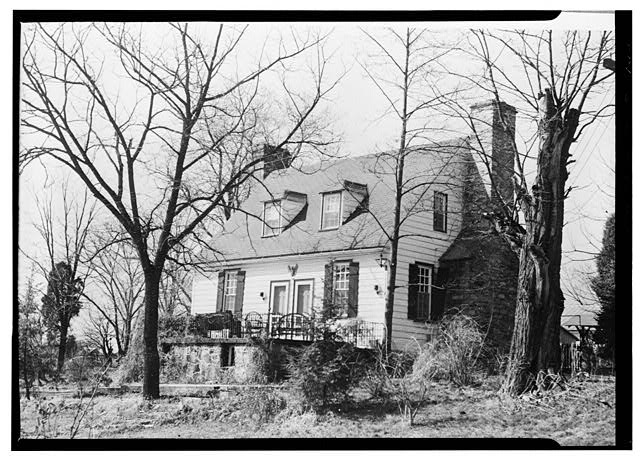

Though widespread, alcohol consumption was often regulated by both legal constraints and social expectations. Anyone wishing to sell alcohol and provide other service to townspeople and travelers alike were required to secure licenses for their establishments. These taverns or inns, otherwise known as ordinaries, were common throughout many of the colonies. Licenses were needed as early as the mid-1600s in some places.[5] In Colchester, many licenses were granted during the town’s short history, though the most important was likely the Colchester Inn, or the Fairfax Arms Tavern, owned by Peter Wagener and managed by Charles Tyler.[6] Under licenses, taverns or ordinaries were often restricted by how long they could be open each day, how much alcohol they could sell, and who they could serve.[7] These legalities were coupled with social expectations. One was expected to control oneself, and this meant no drinking to excess. In the most extreme cases, those in violation of social norms or the law would find themselves publicly humiliated or fined.[8] In these ways, the everyday consumption of alcohol, including rum, was ensured against excess and attempts were made to regulate it for the common good.

Additionally, while the consumption of alcohol was high, so was its opposition. Religious tolerance was common amongst the British colonies. However, some of these religious groups were extreme in their practices against alcohol. They condemned alcohol and many attempted to prohibit the sale and consumption of it. This disdain for alcohol was highlighted in a recent interdisciplinary journal article by Utah Valley University professor, regarding the interactions between Quakers and Native Americans in the mid 1700s. The article states, “Indian and Quaker revivalism intersected through a shared concern for moral purity and regulating alcohol consumption.”[9] This article goes further stating, “For colonists rum generated profit as well as anxieties about its potential disorder.”[10] Meanwhile, sugar plantations in the Caribbean were supplying the foundation for the highly successful rum market. There is no doubt that the rum trade brought wealth to investors and producers. However, this caused concern in towns and religious sanctuaries. This article elaborates on alcohol consumption in the same time period as the Colchester ledgers, providing a broader view and context of the folio pages analyzed.

While rum was an extremely popular drink and part of the culture surrounding the British colonies, it was also heavily regulated by both laws and norms, as well as deemed intolerable by some religious groups. Sugar as a cash crop was extremely beneficial financially to investors and planters. Its versatility made it so, including its importance in the production of rum. Successful sugar plantations were essential for colonial profit while also encouraging the creation, and in turn, the consumption of rum. Thus, sugar plantations and rum consumption created a complex web of interdependencies among various peoples living in the colonies.

[1] Alexander Henderson, et. al., Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 19, 22 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[2] Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761 folio 23 Debit.

[3] Ibid., folio 24 Debit.

[4] Ian Williams, Rum: A Social & Sociable History of the Real Spirit of 1776 (New York: Nation Books, 2005), 166.

[5] Alice Morse Earle, Stage-Coach and Tavern Days (New York: Macmillan Co, 1900), 2, https://archive.org/details/stagecoachtavern00earluoft.

[6] Edith Moore Sprouse, Colchester: Colonial Port on the Potomac (Fairfax, Va: Fairfax County Office of Comprehensive Planning, 1975), 61, https://archive.org/details/Colchester_201704.

[7] Mark Harrison Moore and Dean R. Gerstein, eds., Alcohol and Public Policy: Beyond the Shadow of Prohibition (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1981), 132.

[8] Moore and Gerstein, Alcohol and Public Policy, 137.

[9] Michael Goode, “Dangerous Spirits,” Early American Studies, An Interdisciplinary Journal 14, no. 2, 260.

[10] Goode, “Dangerous Spirits,” 262.