Danielle Roper // AMH 4112.001 – The Atlantic World, 1400-1900

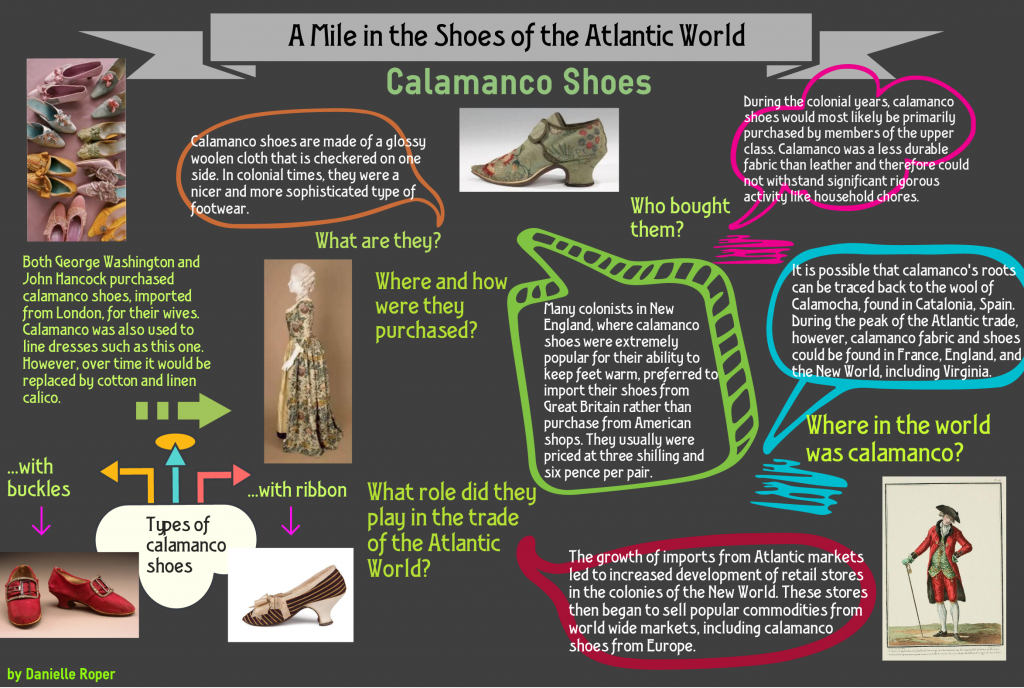

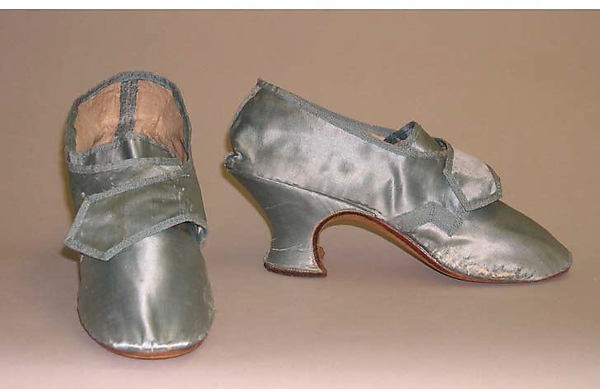

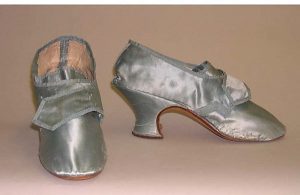

Calamanco shoes were a women’s shoe in the 18th century that were often purchased and worn by members of the upper class. Calamanco is a glossy woolen cloth that is checkered on one side. Lower class women’s shoes would be made of a more durable leather, whereas upper class women’s shoes were made of materials like silk, satin, or calamanco. They were less sturdy than those shoes made of leather and would not be able to withstand a significant amount of rigorous activity. This would make sense given that upper class women would be more likely to afford servants to do their house work for them. Women of the lower class needed shoes that could withstand the many household chores they had to accomplish.[1]

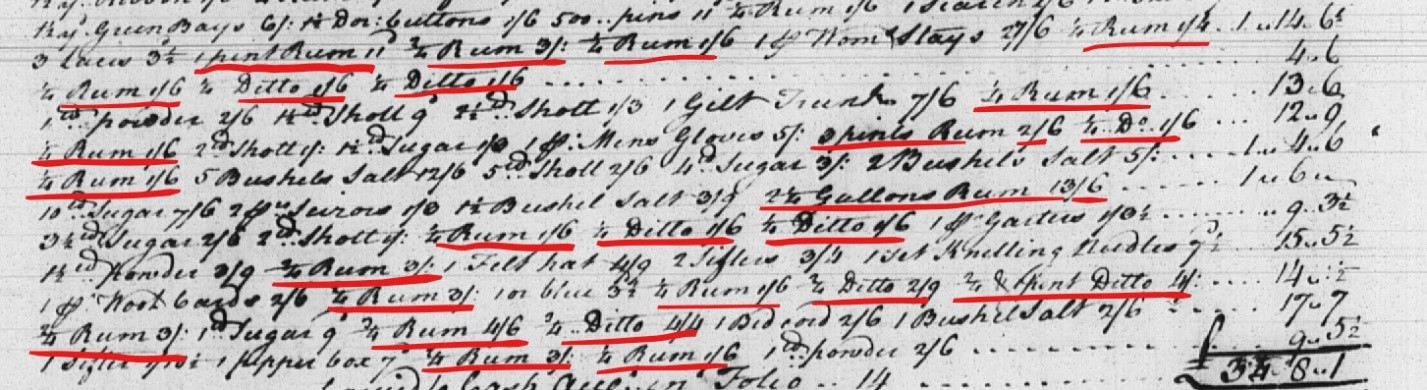

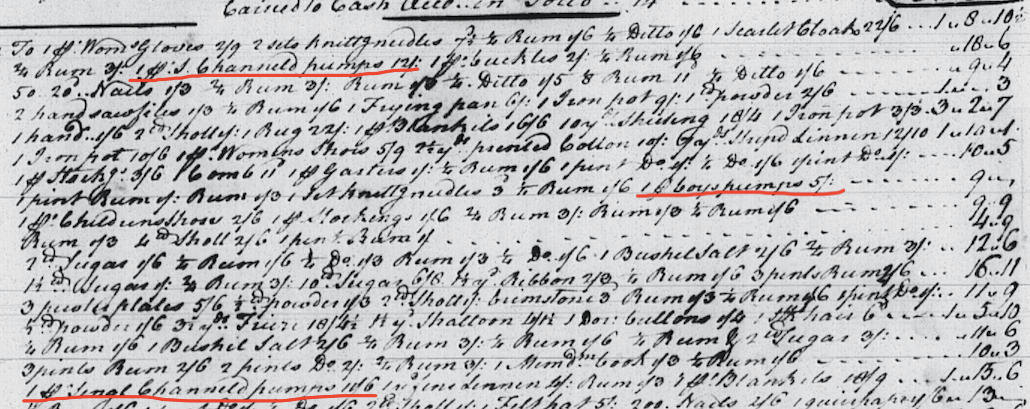

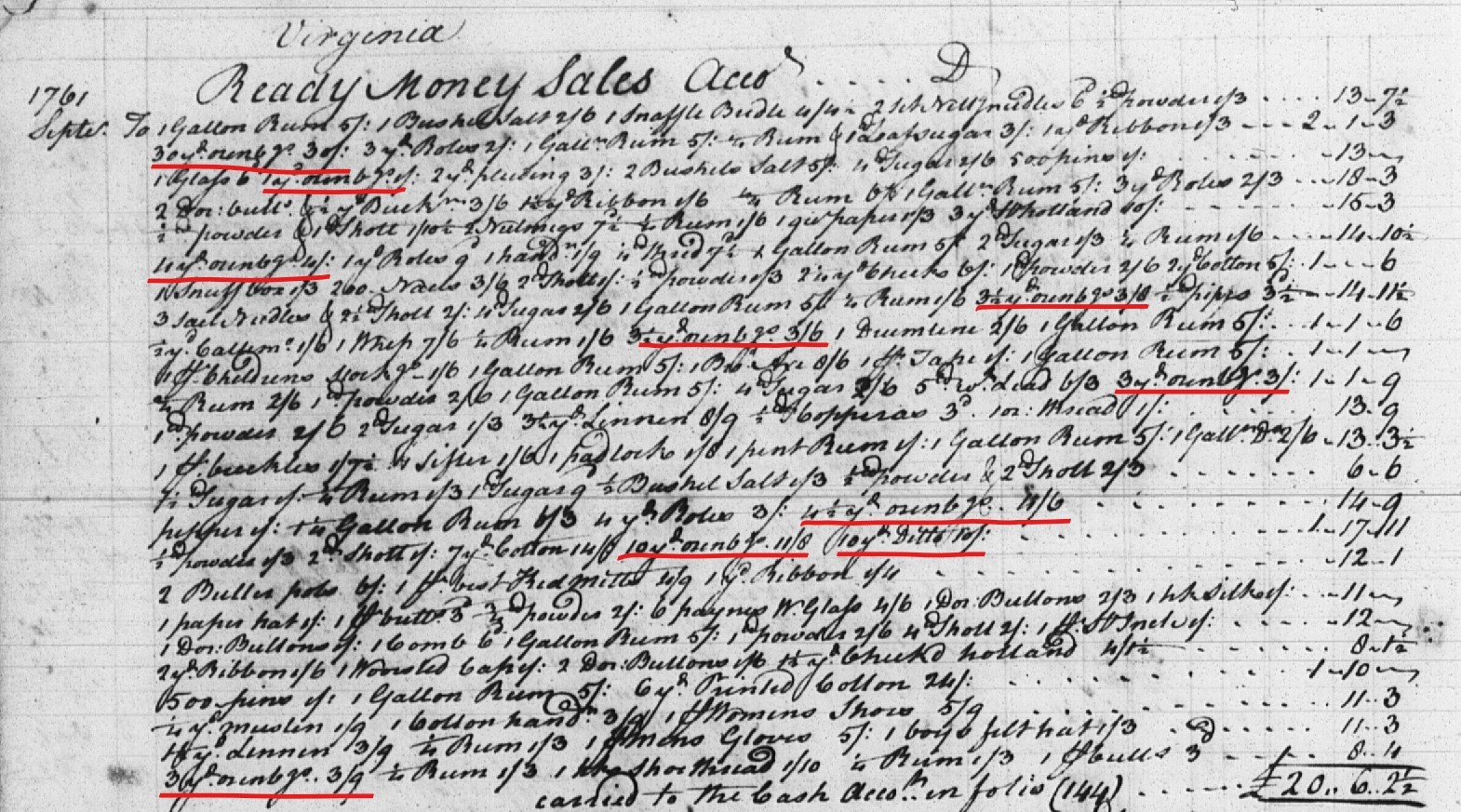

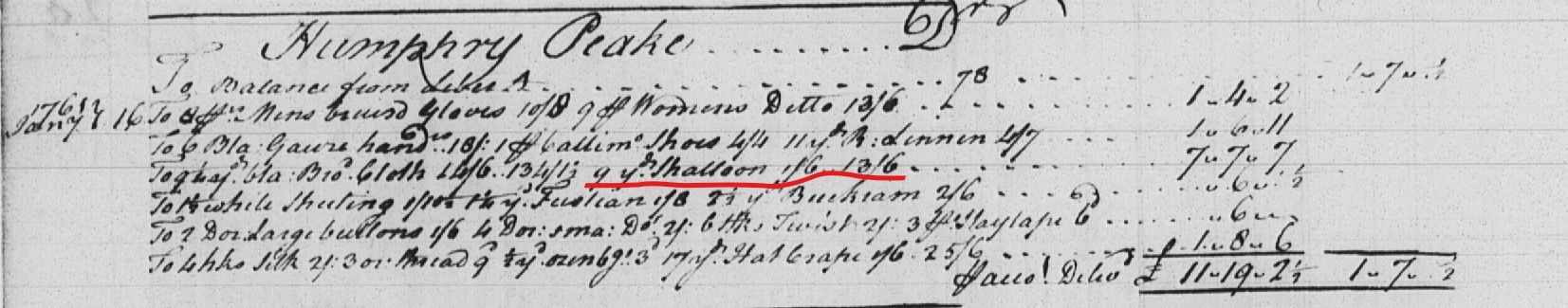

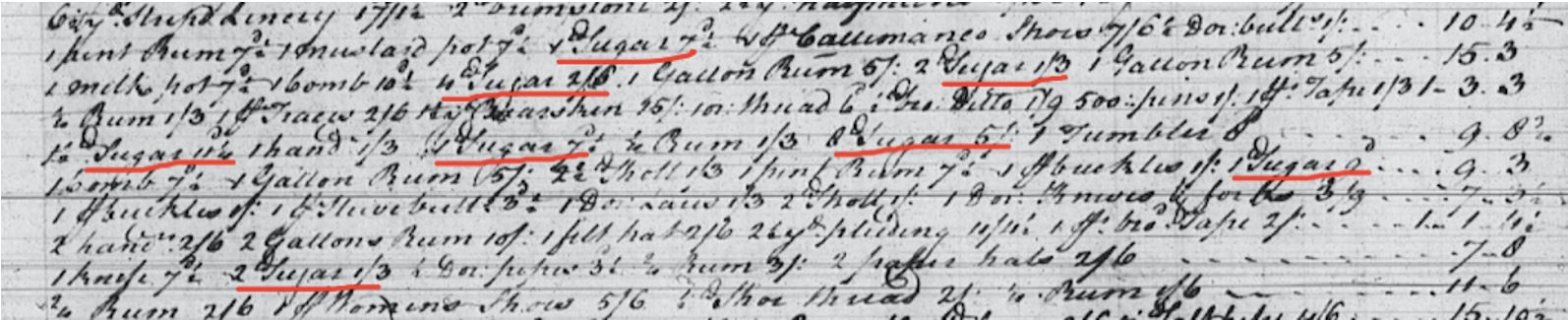

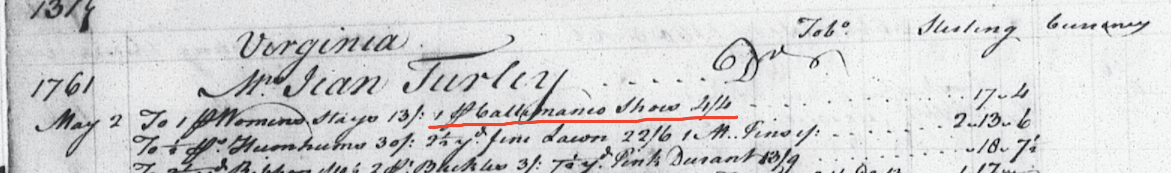

Shoe sizing in the eighteenth century was less precise and consistent so many of the wealthy would send sketches of their feet to special order their shoes.[2] Buckles were often purchased alongside these Calamanco shoes and would be used as a symbol of one’s status and wealth.[3] This can be seen in the ready money accounts of Glassford and Henderson’s Colchester store (1760-1761), when Mrs. Jean Turley purchased one pair of Calamanco shoes along with two pairs of buckles, ribbon, and stays.[4] These purchases could possibly reflect that Mrs. Turley was planning to attend some sort of social event, perhaps a ball. Looking through the shoe purchases in the Ready Money accounts, Calamanco shoes were rarely bought with cash, only being purchased four times.[5] However, regular women’s shoes were purchased twenty-two times. Mrs. Turley paid only four shillings and four pence for her pair of Calamanco shoes; however, the price in the Ready Money accounts was nearly double that at seven shillings and six pence (with one pair being as much as eight shillings). A ‘woman’s shoe’ in the Ready Money account was valued around five shillings and six shillings. Rather than indicating the luxurious nature of the calamanco shoe, this trend may demonstrate the fact that shoes were simply just generally expensive during colonial times, especially when paid for with cash.

Infographic on Calamanco Shoes

[1] Linda Baumgarten. Eighteenth-Century Clothing at Williamsburg. (Williamsburg, Va: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1986).; Giorgio Riello and Peter McNeil. “Walking the Streets of London and Paris: Shoes in the Enlightenment” in Shoes: a History from Sandals to Sneakers. Edited by Peter McNeil and Giorgio Riello. (Oxford ; New York :Berg, 2006).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 131 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[5] Henderson, et. al., Folio 10-13 Debit/Credit.