Brandon Plumlee // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

Nowadays, we say that money doesn’t grow on trees. In colonial Virginia it didn’t grow on trees either, but it did grow on gold-green shrubs. As can be seen in the Glassford and Henderson accounts, clients to the Colchester store (1760-1761) overwhelmingly used tobacco to purchase

their goods and services, far more so than cash. In fact, it has been estimated that by the time of the American Revolution, a full two-thirds of the population of the Tidewater and Piedmont regions of Virginia grew tobacco, even after a move to grow more wheat.[1] The people of colonial Virginia, both in the Tidewater and Piedmont regions, were literally growing their own money. So pervasive was the use of tobacco as currency that one observer in 1740 stated that “they have not the least occasion for paper money.”[2]

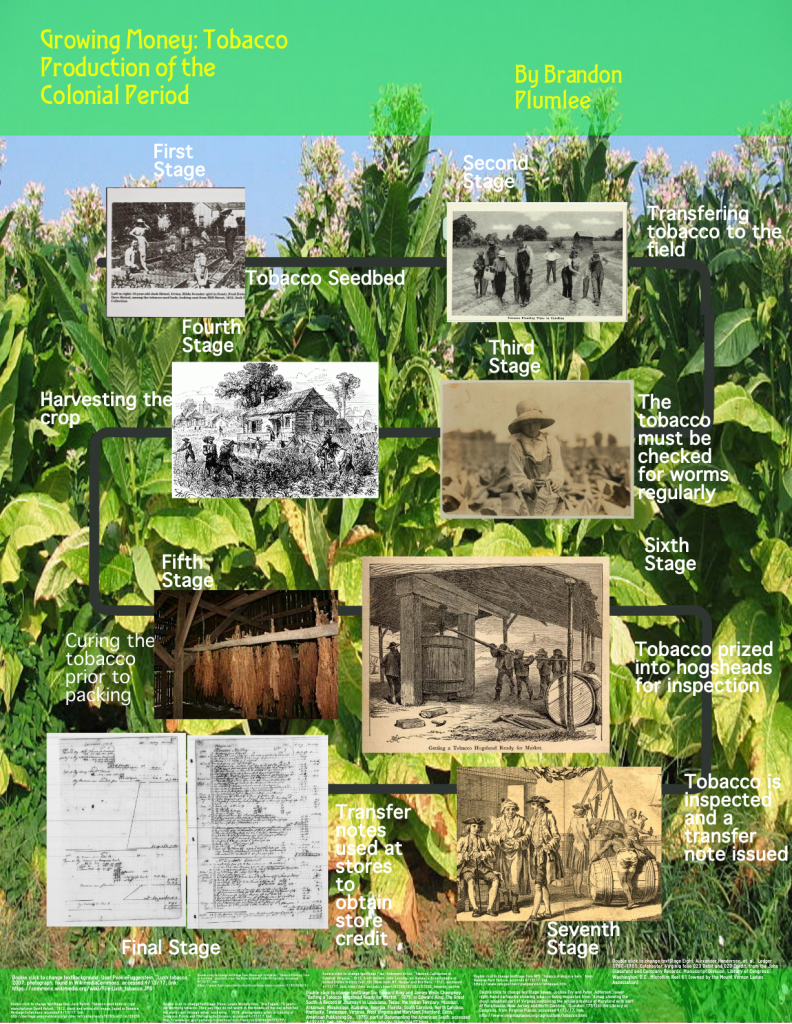

Today we pay for goods and services with cash, but don’t really pay any attention to how exactly that cash is minted or printed. So, how did they grow their money? First things first, it was a very labor intensive process requiring many workers, usually enslaved, at very specific times throughout the growing season. The first step was to germinate the plants in small seedbeds until the plants were big and strong enough to transplant into the fields. Before the tobacco plants could be planted, field hands had to build earthen mounds about a foot or two high and approximately three to four feet apart. This task was the most time consuming and labor intensive since the mounds often required being rebuilt several times throughout the season. After ensuring that the seedlings wouldn’t be choked by weeds, the growing plants would have to be “primed,” meaning the lowest hanging leaves were removed to improve overall tobacco quality. Tobacco had to be constantly monitored for pests and disease, as it is highly susceptible; field hands went out daily to check for tobacco worms.[3]

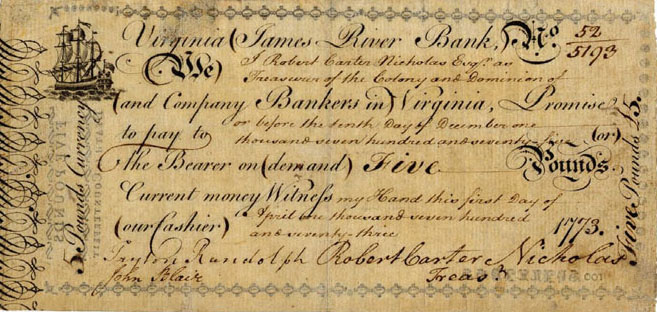

Assuming the tobacco survived all of these growing challenges, the harvesting season usually occurred in late summer during the dog-days of August and September. The problem was that each individual plant would be ready at a different time, meaning hands had to go out to the fields many times and gather up all the plants ready for harvest. However, if they waited too long, an early frost might kill whatever plants were left in the field. After the plant was cut, it was taken to a barn or similar place and hung up to be “cured.” In the very early days, the farmers would simply leave the tobacco on the ground and cover it with hay or straw, but they quickly learned that hanging the leaves was far more effective. The process of curing took about a month to complete, assuming that it was done properly and mold didn’t damage any of the tobacco. It was then “prized,” or put into large casks called hogsheads. A hogshead’s weight varied slightly but was officially 1000 pounds of tobacco.[4] It is at this point that the tobacco would have been inspected and a tobacco note issued. This note would have been given to Henderson, or one of his employees, for store credit.

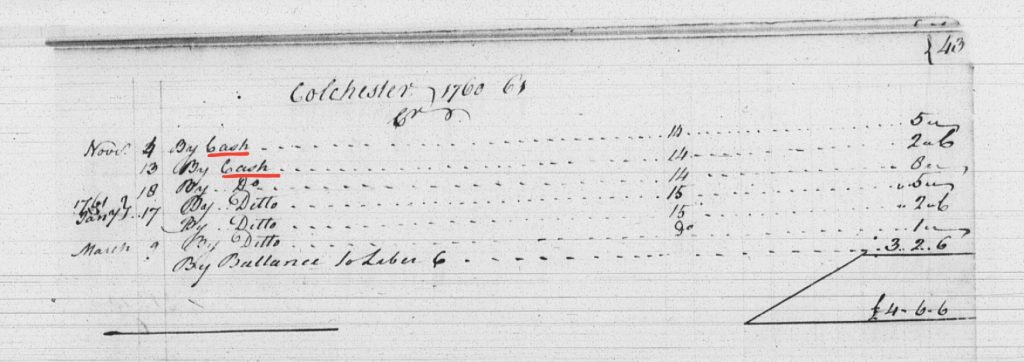

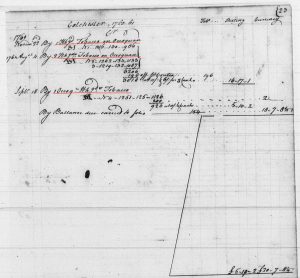

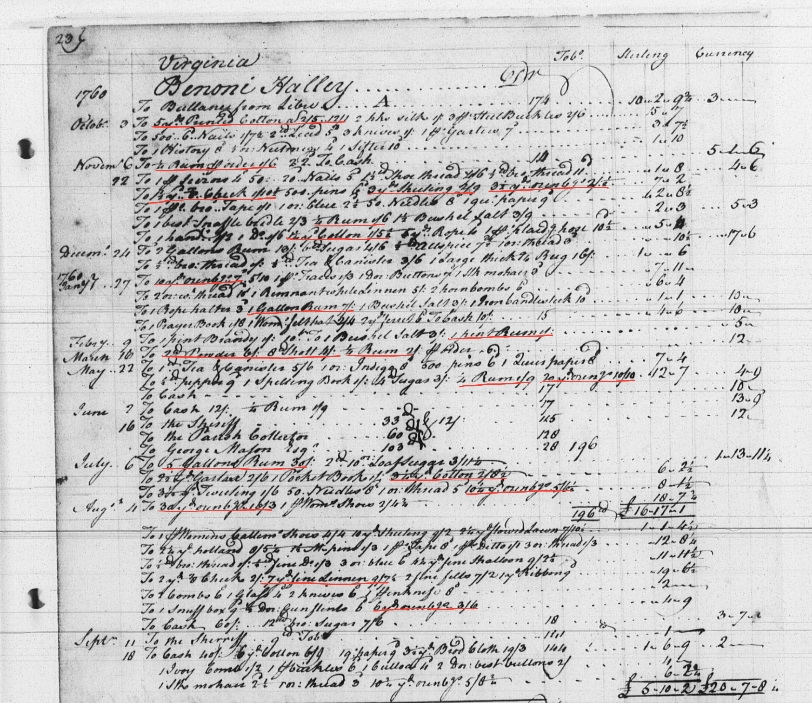

These hogsheads of tobacco were what were used as currency in just about any store in the colonial Chesapeake region. The credit pages of Glassford and Henderson’s ledgers abound with information on the various weights of the hogsheads. For example, a customer of the Colchester store, Benoni Halley, paid the store a total of 4 hogsheads for purchases in the store – that’s roughly 2 tons of tobacco![5] Henderson gave him a little over £22 sterling worth of credit.[6] To put this into perspective, the annual income of American colonists was £15.6, which means that Mr. Halley would have been able to live quite comfortably off of his tobacco for that year.[7] With his credit, Mr. Halley was able to buy goods ranging from cloth to rum to gunpowder.[8] It is safe to say that people throughout the colonial Chesapeake were growing their own money.

[1] Drew A. Swanson, A Golden Weed: Tobacco and Environment in the Piedmont South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 20.

[2] William Keith, “A Discourse on the Medium of Commerce,” in Collection of Papers and Other Tracts, Written Ocasionally on Various Subjects: To Which Is Prefixed,

by Way of Preface, an Essay on the Nature of a Publick Spirit (London: Printed by and for J. Mechell, 1740), 209,

http://galenet.galegroup.com.ezproxy.net.ucf.edu/servlet/Sabin?dd=0&locID=orla57816&d1-

SABCP01767900&srchtp=b&c=19&df=f&d2=1&docNum=CY3802082052&b0=tobacco+planting&h2=1&vrsn=1.0&b

1=0X&db=Title+Page&d6=1&ste=10&stp=DateAscend&d4=0.33&n=10&d5=d6.

[3] “Tobacco: Colonial Cultivation Methods,” National Park Service Historic Jamestown, last modified unknown, accessed March 20, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/tobacco-colonial-cultivation-methods.htm.

[4] National Park Service, “Tobacco: Colonial Cultivation Methods.”

[5] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 23 Credit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[6] Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761 folio 23 Credit.

[7] Peter H. Lindert and Jeffery G. Williamson, “American Colonial Incomes, 1650-1774,” Economic History Review 69, no. 1 (2014): 57.

[8] Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761 folio 23 Debit.