Jason FitzGerald // AMH 4112.001 – The Atlantic World, 1400-1900

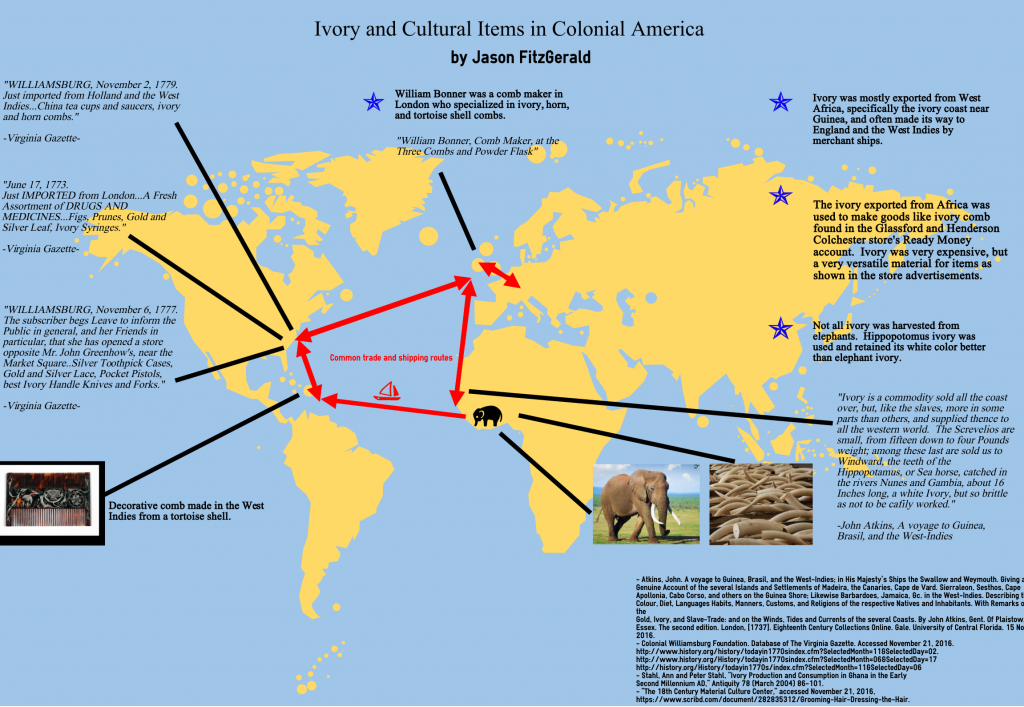

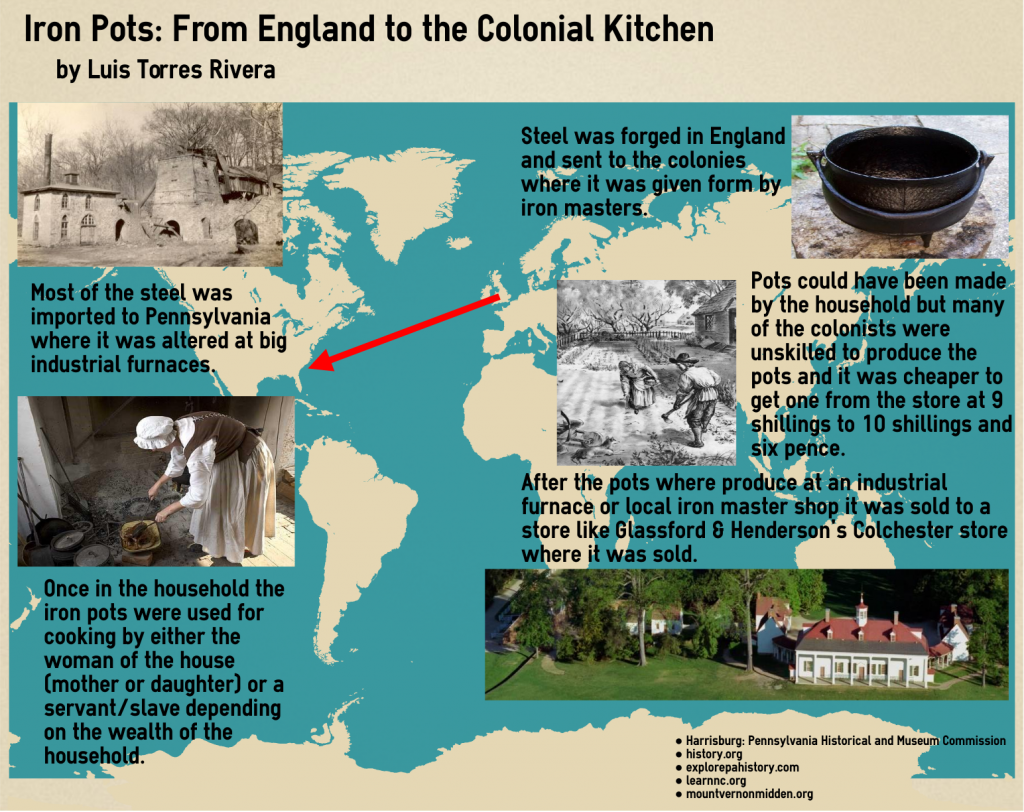

The concept of colonial America being a rural environment when compared to a richly expanding British empire probably sticks in most people’s minds when discussing the finer things of life and items made with elaborate materials. The comb, a very common instrument, holds little value today and is often taken for granted. Some new perspectives have been highlighted when comparing and contrasting certain items in use during the eighteenth century with the help of the Glassford and Henderson Colchester store 1760-1761 ledger located in the Library of Congress collections.

There were many different uses for combs in the eighteenth century. Combs were used for grooming horses, for separating wool fibers, and for bug infestations as well as for decoration and fashion.[1] A letter by Mann Page to John Norton mentions currycombs, often used for brushing down horses, in a list of items purchased with tobacco.[2] Another use for combs was in the process of making thread from wool.[3] Different combs with different teeth configurations, which determined the thickness and texture of the threads, were employed for such tasks.[4] And finally, the dreaded infestation of lice apparently was at the top of the list for fine-toothed combs, which families today may appreciate the frustrations of the ever-elusive hair mite. What then, might you ask could entice a scholar to examine types of combs purchased from Glassford and Henderson?

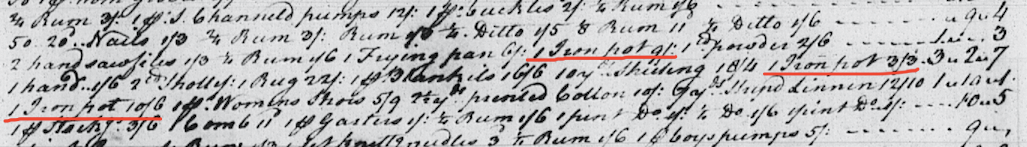

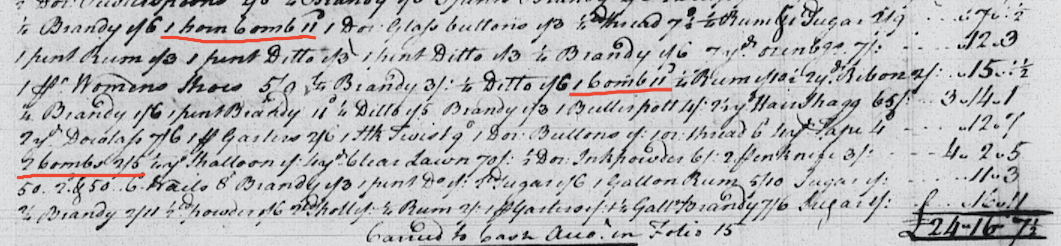

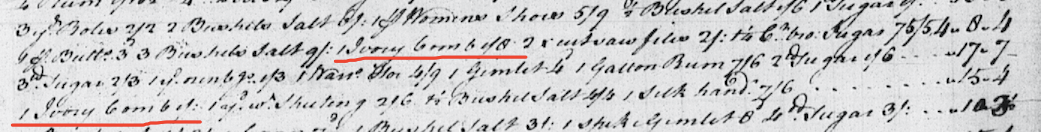

The quality in which combs were made may very well have identified a need for higher quality items not available in what many may have been considered a dank and dirty back water. From October 1760 through December 1761, less than 45 combs were purchased with ready money.[5] Now, it wasn’t because there was a lack of population in need of combs, the inability to fashion a comb in colonial America, or the lack of biting mites. The combs purchased in the ledger, which were made of ivory, horn, or nondescript materials, very well could have represented an item of status sought by higher society. And the fact that these individuals possessed coined money could also have represented the ability to afford lavish items.

The combs purchased in the Glassford & Henderson ledger ranged anywhere from three pence to one shilling and eight pence with the most expensive combs being described as ivory. A further examination into other eighteenth century ledgers could potential lead to similar trends.

One thing for certain is that the want or need for extravagant items existed in eighteenth century Virginia. An individual living in the twenty-first century can easily identify with a Rolex or a Michael Kors handbag, conceivably an item equivalent to that of an eighteenth-century ivory comb. Perhaps a rural environment when compared to a richly expanding empire was not so rural after all.

[1] Karen Clancy, “At the Spinning Wheel,” interviewed by Harmony Hunter, accessed November 9, 2016, http://podcast.history.org/2012/11/12/at-the-spinning-wheel/; David Robinson, “The Bugs that Bugged the Colonists,” accessed November 9, 2016, http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/autumn07/bugs.

[2] “A Page in the Life: Episode Six, Patsy Grenville’s Day,” Colonial Williamsburg, accessed November 9, 2016, http://www.history.org/history/teaching/dayinthelife/pdf/ADITL_Episode6.pdf; Hunter, “At the Spinning Wheel.”

[3] Clancy, “At the Spinning Wheel.”

[4] Clancy, “At the Spinning Wheel.”

[5] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 10 Debit, 11-13 Debit/Credit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).