Caroline Cook // AMH 4112.001 – The Atlantic World, 1400-1900

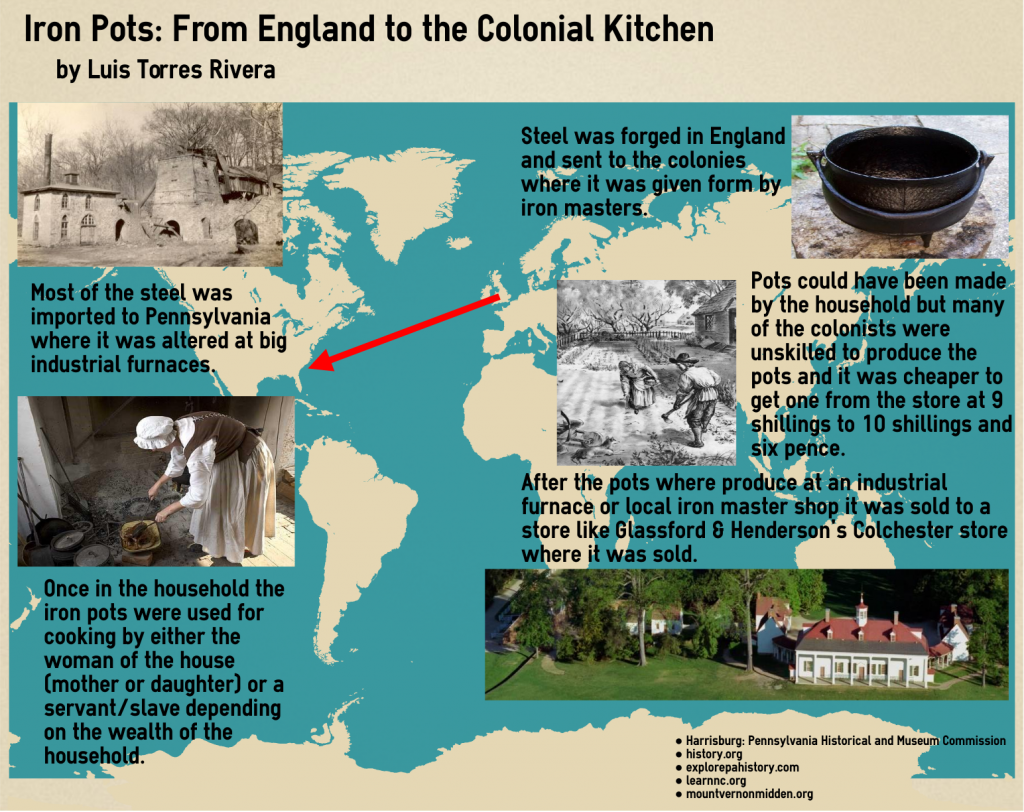

Before currency was regulated in America, purchasing items on debit and credit was a common practice. This not only eliminated currency conversion between colonies, but would also spread out different types of goods within different areas. Many items fluctuated in popularity and could be seasonal, but tools were necessary in any capacity throughout colonial America. The nail was an invaluable tool within the colonial economy that would be traded consistently, helping build the blossoming country’s foundation.[1]

Nails are used primarily for one obvious reason: to build. This means to expand and create new buildings, nails had to be forged of a material that was not only durable, but also easy to find. Most nails were made of cast iron by blacksmiths. Though these cast iron nails were produced and sold by the dozen, nails weren’t cheap. Blacksmiths still had to forge nails individually, since the colonies were not prevented from creating large scale operations due to Britain’s protective trade law. Great Britain had factories and workers that could produce standardized nails quickly and efficiently. This means that nails were typically imported from England into the colonies, bringing more product in at a more affordable rate.[2]

Nails being made at the blacksmith shop at Colonial Williamsburg in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Nails being made at the blacksmith shop at Colonial Williamsburg in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Image courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Journal.

Though not all nails were created equally, blacksmiths would typically produce a nail specific to their own style. Back in England, different blacksmiths would produce different size nails, depending on their client’s needs. [3] For example, some smiths would make their nails more malleable for coffin nails. Other smiths would use different forging techniques for decorative nails. Different ways of producing different nails transferred over into the Americas, showing in the recovery of excavated sites. American nails were usually more crudely fashioned, with less refined edges due to the tools with which they were produced.[4]

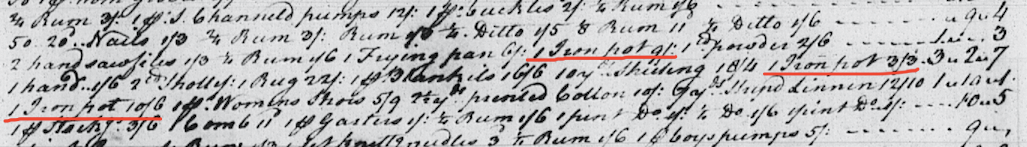

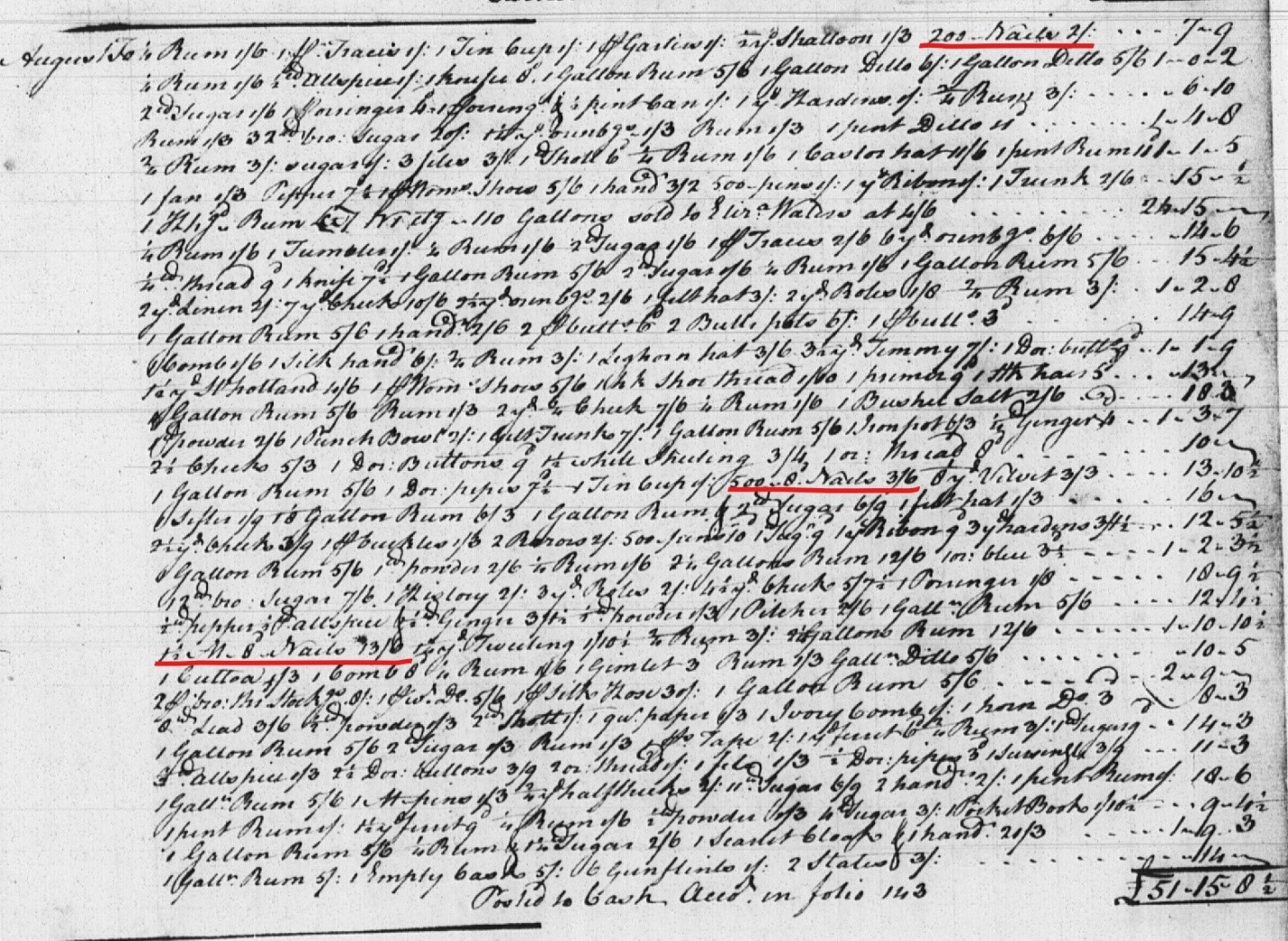

At the Glassford & Henderson Colchester Store from 1760-1761, nails were usually sold by the hundred. In the Ready Money account in 1761, as many as 1500 nails were purchased at a time with the count varying from as few as 50 nails to as many as 1500. There were as many as 33 purchases of nails in that year with cash.[5] Though this may seem like a small amount, nails as a whole were too expensive to buy in really large quantities with cash – 1500 8 pennyweight nails costed 13 shillings and 6 pence. The people purchasing these nails may have needed them for small projects.

Nails purchased at the Glassford and Henderson Colchester store in August 1761 (folio 12).

Nails are one of the most commonly found artifacts at historic sites.[6] But how important were they to a colonial economy? It seems that nails were an import that show up time and again, being unearthed frequently in archaeological digs. A small piece of economic prosperity, nails would be produced in the Americas at an increasing rate over the next hundred years.

[1] Gregory LeFever. “Forged and Cut Iron Nails.” Early American Life. June 2008. Pp. 60-69. Accessed November 6, 2016. http://www.gregorylefever.com/pdfs/Early Nails 2.pdf.

[2] Ibid.; Kenneth Schwarz. “The Nail Market During the Colonial Period.” Making History. 2011. Accessed November 8, 2016. http://makinghistorynow.com/2011/06/the-nail-market-during-the-colonial-period/.

[3] Edward J. Lenik. “A Study of Cast Iron Nails.” Historical Archaeology 11 (1977): 45-47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25615315.

[4] LeFever, “Forged and Cut Iron Nails,” 65.

[5] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 11-13 Debit/Credit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[6] Tom Wells. “Nail Chronology: The Use of Technologically Derived Features.” Historical Archaeology 32, no. 2 (1998): 78-99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25616605.