Ayla Lupien // AMH 4112.001 – The Atlantic World, 1400-1900

By looking back on the ledgers written by Alexander Henderson, a merchant for a store in Colchester, Virginia, in the 1700s, we can learn a lot about the way people lived, the necessities that they purchased, and luxuries that only the wealthy could afford.[1] We can see how people from this time lived, simply from their purchases, as well as find out the names of people living during that era and what kinds of jobs they may have had. Many of the items sold also tell their own story.

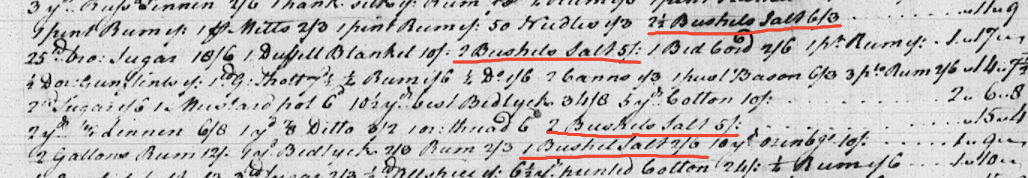

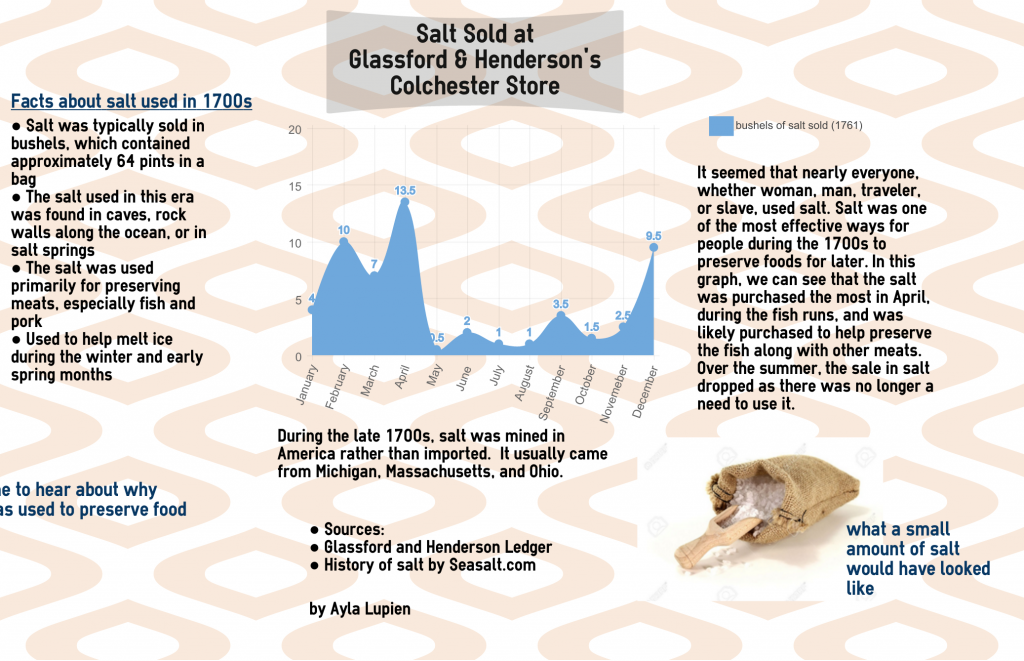

The item I chose to research was salt, a household good used by many during the 1760s; it was purchased regularly at Glassford and Henderson’s store according to the 1760-1761 ledger. A bushel of salt is approximately 64 pints of salt. The salt was in larger chunks that would have to be broken up by the people who purchased it, unlike the fine-grained table salt we use today.[2] The average day-to-day person regularly purchased bushels of salt, but looking at the other accounts, it is clear to see that the salt is most regularly purchased in the fall and spring months by both men, as well as women, such as Elizabeth Fallen who was a seamstress working for the store and being paid in merchandise, like salt.[3]

Salt was a necessity in the lives of nearly everyone living at the time because it was one of the easiest ways to help preserve food. Based on the Ready Money accounts from the Colchester store, there does not seem to be much price variation regarding the salt purchased, however it was purchased in different quantities from half of a bushel up to as much as 5 bushels. Bushels of salt were purchased on 66 separate occasions throughout the year of 1760-1761. The most common months to buy salt were October 1760 (six purchases), December 1760 (nine purchases), January 1761 (eight purchases), March 1761 (six purchases), and April 1761 (fourteen purchases). March and April purchases line up with when the fisheries began operating again as the fish migrated upstream, which means that the people were likely buying the salt to preserve fish for eating later in the year. In April, we begin to see a spike in the purchases of salt, some buying as much as three bushels at once. In addition, in fall and early winter, harvests were coming in and preservation processes were happening to make sure food was kept through the winter.[4] Hogs were also slaughtered at the end of fall or early winter, and would be preserved with salt for use throughout the coming year.

We also see a price hike in the cost of salt as the demand increased. Rather than being 2 shillings and 6 pence, bushels of salt in the spring months cost 3 full shillings. This was likely due to the demand for salt by nearly everyone visiting the store. Because it was purchased during the late fall and spring months, it is widely believed that the salt was predominantly used for preserving foods such as fish and other meats.[5]

By studying the purchases of the people who visited Glassford and Henderson’s Colchester store, we can develop a better understanding of their habits and way of life, which in turn can help us unlock various mysteries of our history.

[1] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[2] “History of Salt,” History of Salt | SaltWorks®. Accessed November 8, 2016, https://www.seasalt.com/salt-101/history-of-salt.

[3] Henderson, et. al. Folio 42.

[4] Rumble, Victoria. “Early American Food and Drink.” Colonial America: The Simple Life. August 2009. Accessed November 09, 2016. http://colonial-american-life.blogspot.com/2009/08/early-american-food-and drink.html

[5] Mickey Parish. “How Do Salt and Sugar Prevent Microbial Spoilage?” Scientific American. 2006. Accessed December 05, 2016. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-do-salt-and-sugar-pre/