Joseph Lolli // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

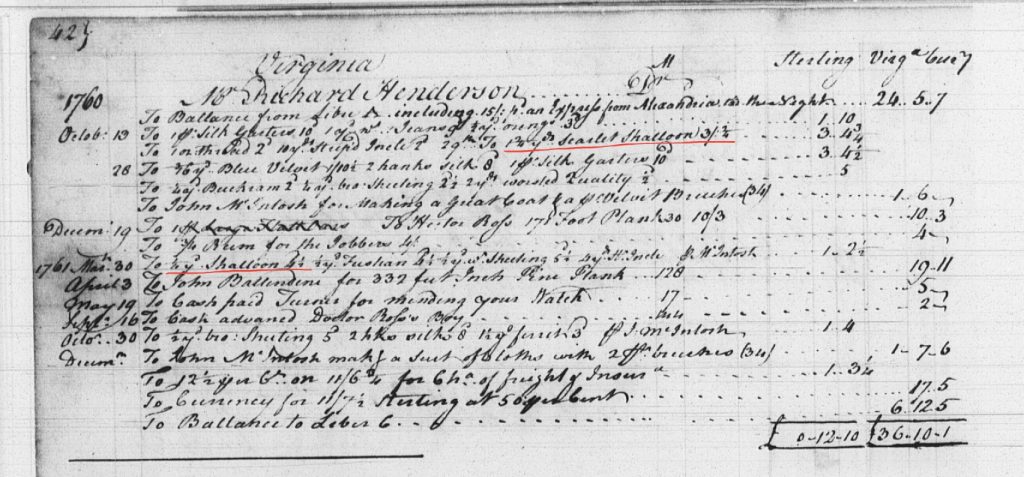

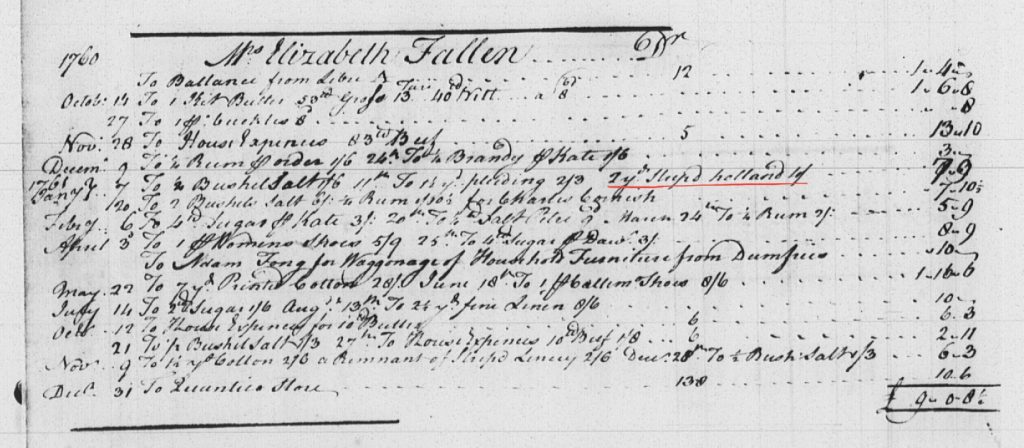

When looking at any documents from the past, you must understand that the words used in their time may mean something completely different than they mean today. Depending on how far back you go, you will also have to become patient with simple things like spelling because there may not be a standardized way of writing a word, and it can be spelled many different ways by the same person, even in the same sentence. While transcribing the Colchester, Virginia store ledger (1760-1761), many entries stumped me in terms of context, until I noticed a pattern in items purchased concerning fabric goods.

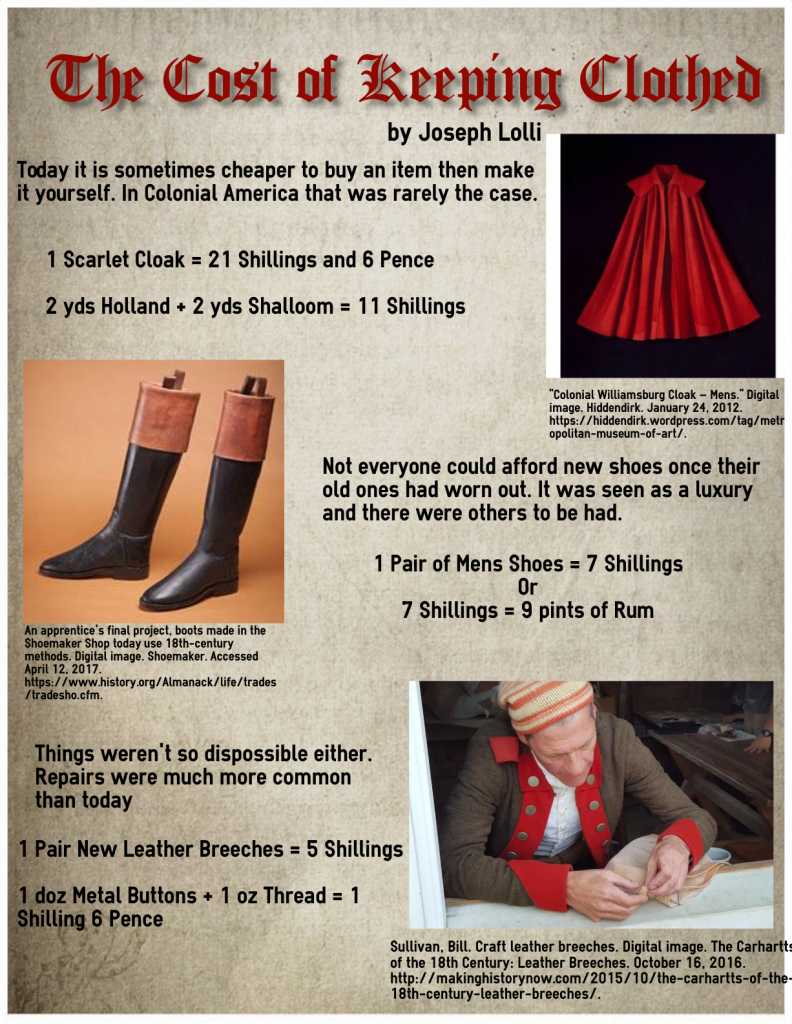

Traditional, well-known fabrics like denim, jean, linen, muslin, satin, silk, and velvet were used. Items that caused confusion due to mixed definitions were alamode, bearskin, drill, holland, and shalloon.[1] Alamode is today used to refer to ice cream with pie, though its origin is the French saying a la mode meaning “in the fashion of.” To the craftsman of the eighteenth century, it was a lightweight silk fabric used for scarves and hoods.[2] Bearskin was not literally referred to as the skin of a bear, but instead it was a thick, woolen cloth often provided to slaves as outerwear.[3] Drill is not an electronic power tool used in construction; drill in the accounts was a strong, twilled cotton often used for summer clothing.[4] Ask most people what holland is and they will tell you it is a country. Ask the shopkeeper in Colchester, and you will be supplied with a linen fabric which got its name from where it was made.[5] Something like shalloon would sound foreign to the average American, though it was a very common, cheap, wool cloth used for lining clothing and pockets.[6]

If you take a good look through the Glassford and Henderson ledger from the mid-eighteenth century, you’ll find that the usual fabrics from today and the more unusually titled fabrics explained here were bought in similar volumes and similar frequency. When you find something shocking, strange, or at odds with your modern perspective during research of an era past, fear not. There is likely a very simple explanation when you look into the context and add a little more digging into your research.

[1] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 52, 59, 158 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[2] Dictionary.com, “Alamode,” accessed March 23, 2017, http://www.dictionary.com/browse/alamode.

[3] Gaye Wilson, “Slave Clothing,” Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, accessed March 23, 2017, https://www.monticello.org/site/plantation-and-slavery/slave-clothing.

[4] Dictionary.com, “Drill,” accessed March 23, 2017, http://www.dictionary.com/browse/drill.

[5] Linda Baumgarten, “Looking at Eighteenth-Century Clothing,” Colonial Williamsburg Online Resources, accessed March 23, 2017, http://www.history.org/history/clothing/intro/clothing.cfm.

[6] Peter Earle, Making of the English Middle Class: Business, Society, and Family Life in London (London: Methuen, 1991), 288.