Kayla Davis // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

When reading about colonial life in the British colonies during the mid-eighteenth century, it is easy to think of their consumer habits as idyllic or self-reliant, as we often reference the homespun movement preceding the American Revolution.[1] Beginning in 1765, after the implementation of the Townshend Acts, this movement encouraged colonists to stop buying manufactured goods from Britain and instead produce them themselves.[2] However, as sources and account books reveal, the decades leading up to the imposition of the Townshend Acts prove the economy of the colonies cannot be relegated to the same image as that of the colonies during the Revolution as it was a little more complicated. The 1760-1761 account book from John Glassford and Alexander Henderson’s Colchester store in Virginia and varied scholarly research uncovered that the economy of colonial America was a complicated mix of imports and home-manufactured goods.

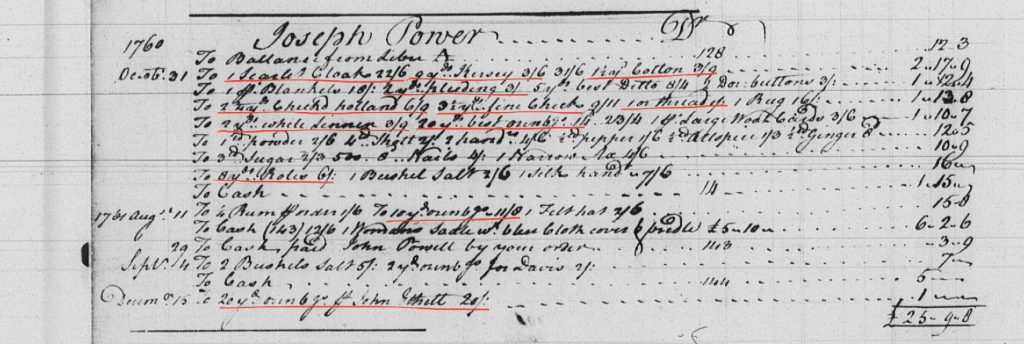

The middle of the eighteenth century saw an increase in the size of flocks of sheep and a cultural movement towards rejection of luxury cloths for simpler wools and flax of American production; this coincided with a thriving economy in the colonies.[3] The accounts of the Colchester store in Virginia suggest commercial trade for textiles. Joseph Power bought yards of strong durable textiles and other materials which indicate he (or someone in his household) was making clothing. On October, 31, 1760, he purchased one and a half yards of cotton, nine yards of kersey, two yards of white linen, one ounce of thread, and two dozen buttons. Additionally, Power bought other fabrics such as best pleiding, checked holland, fine check, and yards of various other kinds of fabric. Fine check and checked holland cost the most, while the fabrics of osnaburg and roles were the least expensive.[4] These purchases of various fabrics—as well as the materials needed to turn fabric into clothing, such as buttons and thread—indicate that Power was buying supplies with the intent to manufacture clothes.

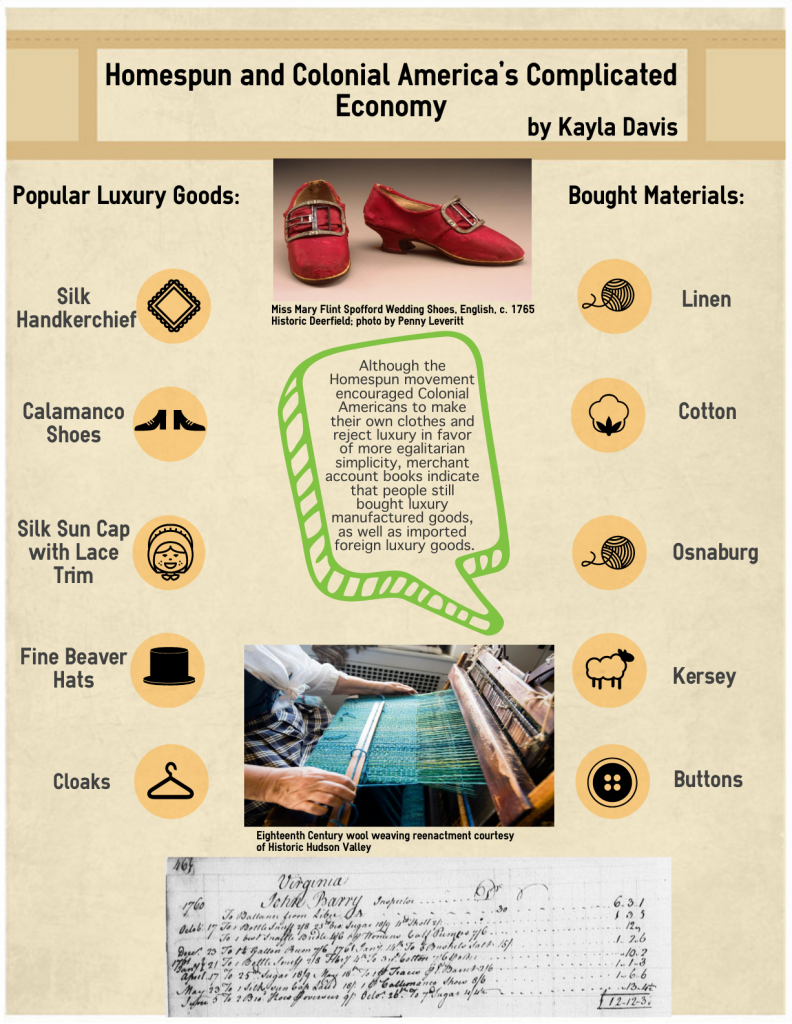

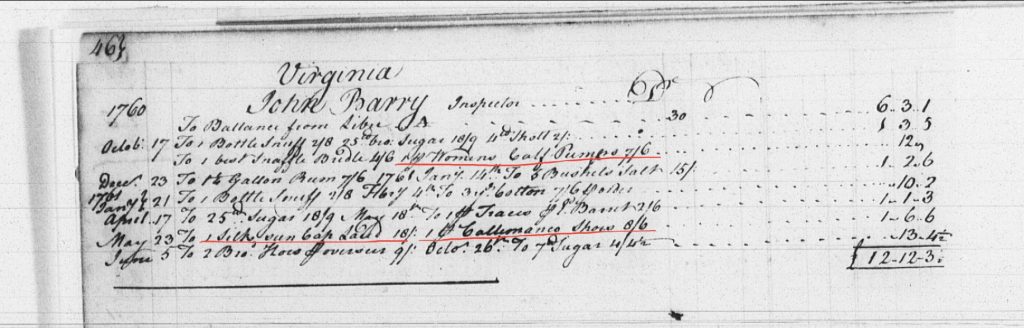

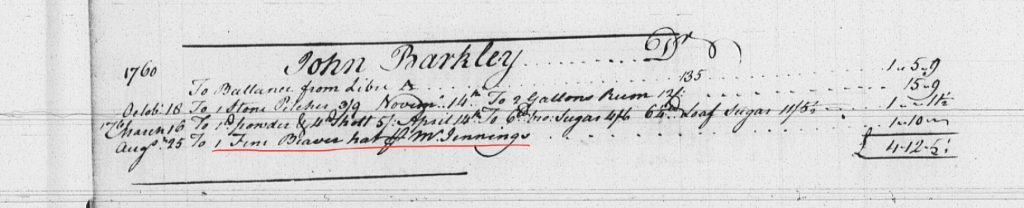

At the same time, one cannot conclude that there were no luxury goods consumed during this time either; in Virginia, the account book shows us that patrons of the Colchester store did buy luxury and manufactured goods. In 1760, Joseph Power also bought a scarlet cloak, and a silk handkerchief, which would have been imported luxury goods.[5] In 1760, John Berry, an inspector at the Occoquan tobacco warehouse, purchased a silk sun cap with lace, as well as two different kinds of shoes: a pair of women’s calf pumps and a pair of Calamanco shoes.[6] In the same year, John Barkley purchased a fine beaver hat.[7] The purchase of goods like the cloak, the beaver hat, and the shoes indicates that there was an economy for manufactured goods. However, even more interesting is the purchase of silk items like the handkerchief and the cap, which indicate a market for luxury imported items.

What is important is the realization that the American colonies were complex, and often present to us a different picture than the quite generalized image we are given in textbooks. When shown wonderful sources such as the accounts of the Glassford and Henderson Colchester store, we see that the American colonies were a diverse and complicated group of communities with many different stories to tell.

[1] Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York: Vintage Books, 2001), 177-183, accessed April 17, 2018.

[2] Michael Zakim, “Sartorial Ideologies: From Homespun to Ready-Made,” American Historical Review, 106, no. 5 (2001): 1554.

[3] Zakim, “Sartorial Ideologies,” 1557.

[4] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 59 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[5] Henderson, et. al., Ledger 1760-1761 folio 59 Debit.

[6] Ibid., folio 46 Debit.

[7] Ibid.