Katie Miesner // AMH 4110.0M01 – Colonial America, 1607-1763

The eighteenth century was truly a time of cultural melding in the colonies. People from various parts of Europe with aspirations for a better life came to Virginia, largely because of its flourishing economy. For immigrants, Virginia offered refuge from religious persecution, poverty, and social oppression. Shopkeeper Alexander Henderson operating the John Glassford & Company store in Colchester, Virginia, was an example of a colonist who came to America seeking more opportunities.

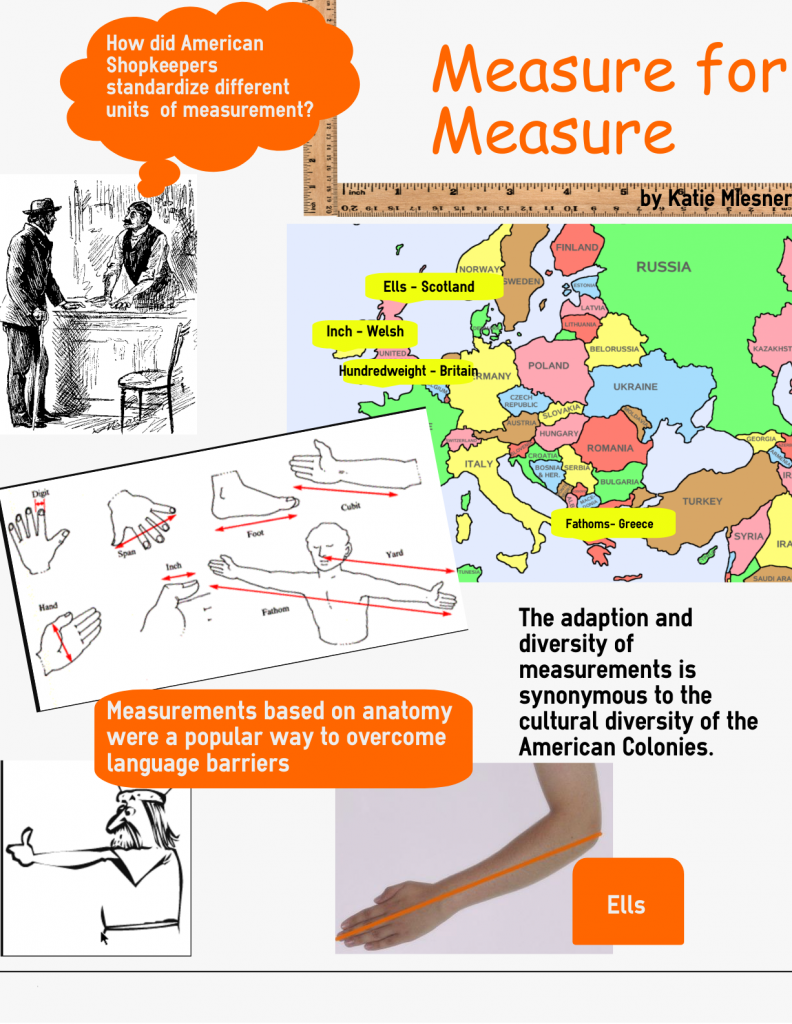

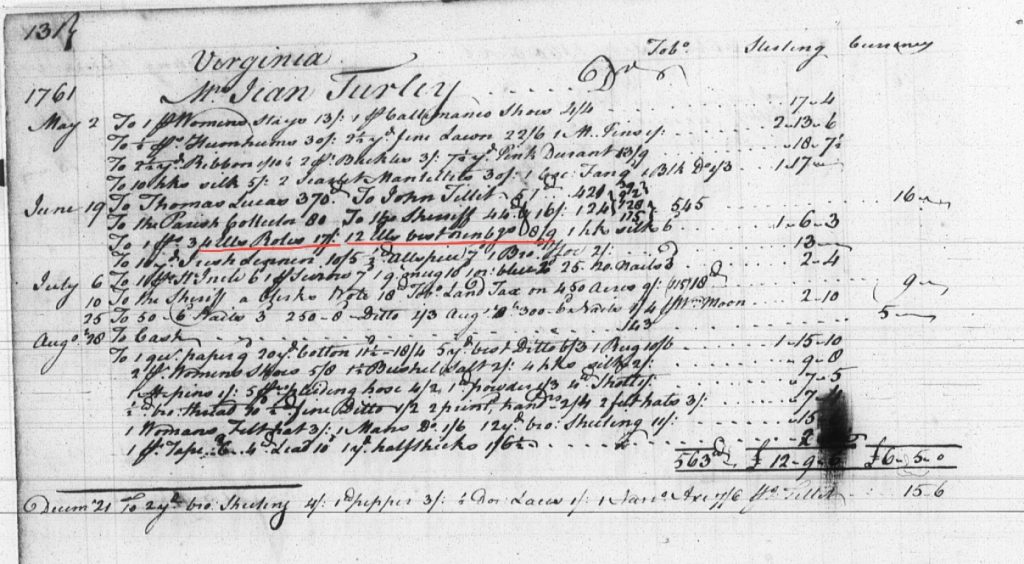

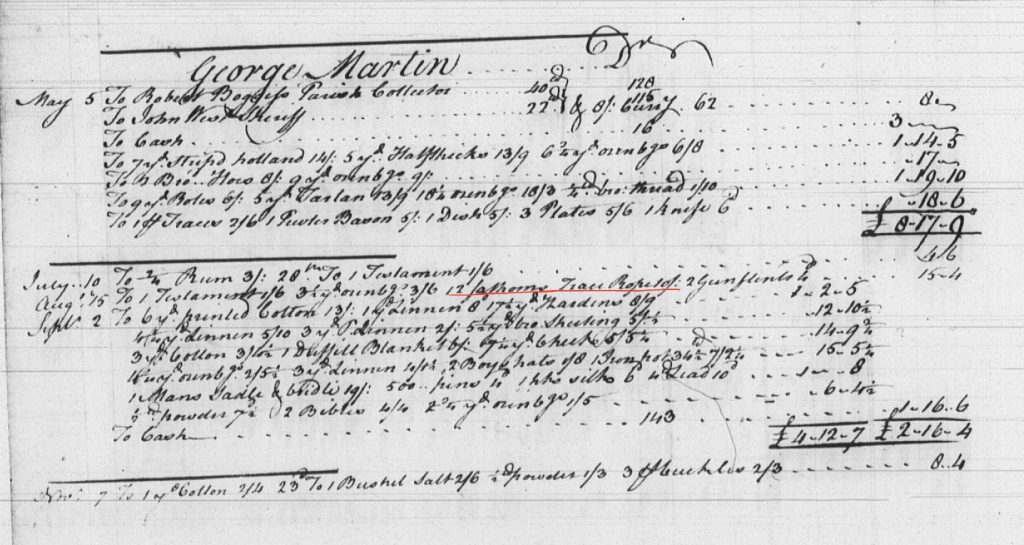

When analyzing Henderson’s shop ledger for 1760-1761, I was initially thrown off by the various units of measurements found in the accounts.[1] Certain units such as inches, yards, and pounds sounded familiar while other words such as ells, fathoms, and hundredweights required a fast search into the project’s glossary for clarification. I soon learned that a hundredweight (abbreviated cwt) is a unit of weight, a fathom is a measurement of length described as outstretched arms, and an ell was also used for length, typically in Scotland and England, gauged by the length of a forearm.[2] I began pondering how Henderson was able to keep track of all of these different units of measurement. In order to be successful in his line of work, he must have learned to be patient and adaptive to numerous cultures and find ways to get around language and social barriers that come with dealing with lots of people from various backgrounds. To succeed in business, he must have had to do a lot of improvising in terms of consolidating fair trade prices to reflect the various units of measurement depending on the item sold. The more I pondered these scenarios, the more I realized that the various units of measurement are synonymous with the colonists themselves.

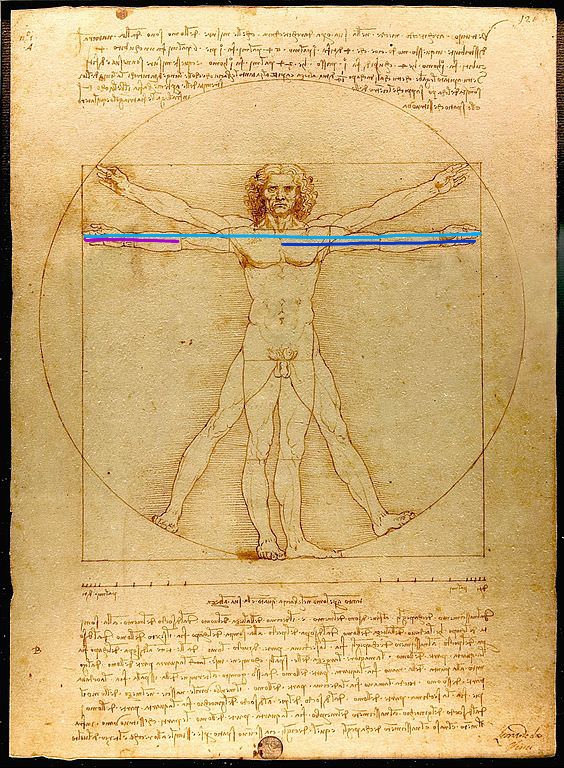

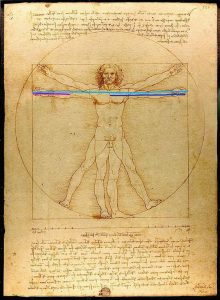

The United States Customary Unit system’s origin is similar to the British Imperial system. Both systems trace their roots back to Roman and Anglo-Saxon units of measure.[3] As I reviewed the accounts, I found that the most common type of length measurements used in the ledger were inches, yards, and fathoms. What’s interesting about these types of measurements is that they are all units based on anatomy and dimensions of the human body. According to Russ Rowlett, a professor from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, “the inch represents the width of the thumb, [and] in many languages the word for inch is also the word for thumb.”[4]

The foot is often thought of as being the length of a human foot, and the fathom as previously stated is a person’s wingspan. The yard can also be interpreted as being the total distance from the end of the middle finger of an outstretched hand to the nose, or half of a fathom.

What this says about the eighteenth century is that because of the lack of similar backgrounds and common education, units of measurement that relied on anatomy were easier to use than those dependent on math, numbers, or previous knowledge. This idea predates the eighteenth century, but was revisited as a means to find commonality to overcome language barriers.

Although there wasn’t an official decree in terms of a unit of measurement in the United States until the Metric Conversion Act of 1975 by President Ford, a need for a practical system of measurements was certainly a priority for shopkeepers such as Alexander Henderson in eighteenth-century colonial Virginia.[5] The adaption of colonial shopkeepers to numerous cultures as seen in the ledger proves that, while everyone has different origins, money and goods are a universal necessity.

[1] Alexander Henderson, et. al. Ledger 1760-1761, Colchester, Virginia folio 131 Debit, from the John Glassford and Company Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Microfilm Reel 58 (owned by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association).

[2] History Revealed, Inc., Glassford and Henderson Transcription Glossary, unpublished.

[3] Russ Rowlett, Dr, How Many? A Dictionary of Units of Measurement (New York, NY: University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, 1999).

[4] Rowlett, How Many?.

[5] “Metric Conversion Act of 1975,” US-Metric Association, accessed March 23, 2017, http://www.us-metric.org/metric-conversion-act-of-1975/.